Thanks for a fun class and fun term! It’s been lovely to work with you all!

Don’t forget to send me ALL of the following:

- Final Draft

- Writer’s Memo (see prompt)

- Peer Review worksheets

Thanks for a fun class and fun term! It’s been lovely to work with you all!

Don’t forget to send me ALL of the following:

I mentioned this in class, but wanted to post the link and a description. There’s a set of games called Victorian Mysteries that includes The Moonstone.

I forgot that you play the “role of Detective Cuff” and wade through suspects.

The game is pricey for the computer download– $9.99– but is only a couple of dollars for iPad and iPhone. Sadly, no Android version as of now, but I am happy to let people play with it before class Friday.

In the meantime, you can watch the video here:

I cannot help but struggle with the narration of this novel. After reading Jane Eyre and the various post-colonialist critiques, I struggle with accepting and moreover trusting Betteredge’s narration of the story. As Betteredge is the head male servant to the Verinders, his judgmental commentary of the Indian men sent to retrieve the moonstone is anything but just. As he is a white lower class male, his narration of the Indian men who must disguise themselves in lower class attire in their attempt to re-obtain the moonstone. All of this is backwards and flipped on its head, as Betteredge can only move upwards, and really has no authority to be speaking or commenting on the Indian men. Moreover, Betteredge’s bias towards the white people he is surrounded by makes him an unreliable narrator. For him to claim the moonstone as the property of the white upper class, when it is a stolen piece of property from the Indian upper class screams of bias. With arguments like that of O’Conner and Spivak, accepting the narration of Betteredge would be accepting the underlying racism. Whereas with Jane Eyre the criticism focuses on the language surrounding Bertha Mason, the imperialist leanings in The Moonstone are not solely in the language, but the overall attitude regarding the Indian culture that these characters choose to remain ignorant about. Thus, the loss of the moonstone remains almost like a work of karma, yet as it was again stolen perhaps it is more an indication of the greed and entitlement of white colonists that Collins is commenting on. Whether it is Colllins’ ignorance which is the driving force behind Betteredge’s bias, or instead a way of Collins to critique the outlook of 19th Century imperialist thinking remains to be seen. Neverthless, Betteredge’s narration is biased, and accepting his word is accepting the racist undertones.

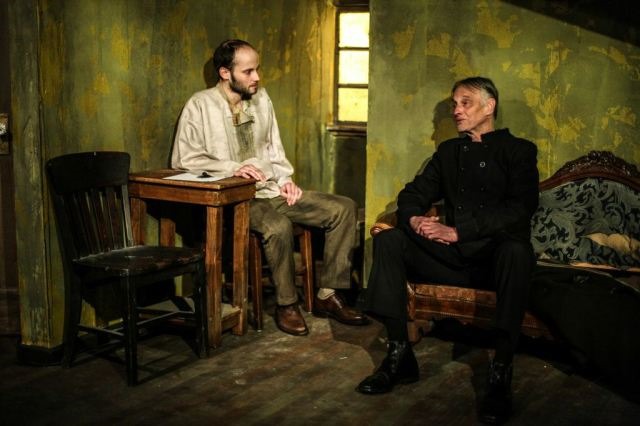

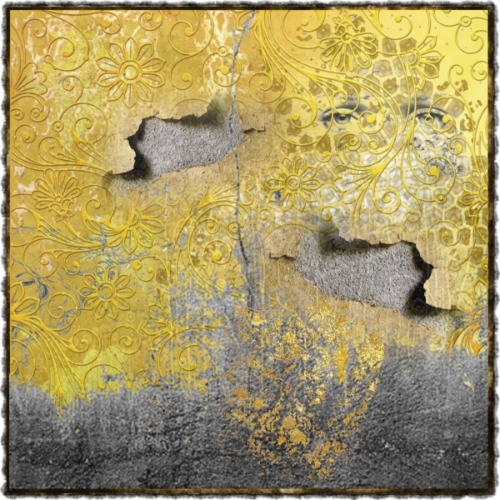

Reading Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper has completely changed my reading of my favorite novel, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment: Namely, that “yellow wallpaper” is a theme of principle importance in Dostoevsky’s novel. The protagonist of Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov, is a poor student who lives in a small attic room in St. Petersburg. Early on in the novel, he murders the local pawn broker as well as her sister (though only the first is premeditated). The question that scholars have grappled for years is, what was Raskolnikov’s motive for murder? I believe it can be argued that his yellow wallpaper is what drove him to his crime.

In Crime and Punishment, all of the character’s rooms coincidentally have yellow wallpaper: Raskolnikov’s; Aloyna Ivanovna’s, the pawn broker he murders; Sonya’s, the prostitute who seeks to redeem him; and even the hotel rooms. Dostoevsky describes Raskolnikov’s room as having “yellow dusty wall-paper peeling off the walls that gave it a wretchedly shabby appearance” (23). Yellow wallpaper is something the characters cannot escape. And like Jane in The Yellow Wallpaper, Raskolnikov is obsessed with wallpaper.

After committing murder and returning to his room, Raskolnikov immediately stuffs what he has stolen into his wallpaper. This causes him undue anxiety due to its conspicuousness; he later removes the stolen goods and tosses them under the bridge in the water, not really wanting what he had stolen in the first place. What struck me as significant after reading Gilman’s work is Raskolnikov’s strange fixation on wallpaper. For instance, when visitors come to visit Raskolnikov he turns away from them on his bed and stares at the wall instead:

“Raskolnikov turned to the wall, selected one of the white flowers, with little brown lines on them, on the yellowish paper, and began to count how many petals it had, how many serrations on each petal and how many little brown lines. He felt his arms and legs grow numb as if they were no longer there. He did not stir, but looked fixedly at the flower.” (Dostoevsky 114)

It seems here that Raskolnikov has become a victim to the wallpaper, as if it is overtaking him. The more he absorbs himself in it, the number he feels. This numbness does not seem to be comforting but excruciating—we see this when Raskolnikov finally turns away from the wallpaper:

“[Raskolnikov’s] face, now that he had turned away from the engrossing flower on the wallpaper, was extraordinarily pale and had an expression of intense suffering, as though he had just undergone a painful operation or been subjected to torture.” (Dostoevsky 122)

Compare this with Jane’s similar quote in The Yellow Wallpaper:

“The color is hideous enough, and unreliable enough, and infuriating enough, but the pattern is torturing.” (Gilman 9)

The wallpaper has a hypnotic but toxic quality. Like a bee drawn to nectar, Raskolnikov is drawn to the flower—it compels and traps him. And like Jane, he seems to become lost in the intricate haphazardness of its design.

Though yellow wallpaper causes Raskolnikov undue pain and suffering, for some reason, he finds himself fond of it. We see this when he returns to the flat of the pawn broker he killed:

“[The workmen] were putting new paper, white, with small lilac-colored flowers, on the walls, in place of the old, rubbed, yellow paper. For some reason Raskolnikov violently disapproved of this, and he looked with hostility at the new paper, as though he could not bear to see it all changed.” (Dostoevsky 146)

This is an oddly strong reaction that Dostoevsky never explains. Raskolnikov’s attitude is comparable to Jane’s, who at one point states that she is fond of her room “in spite of the wallpaper. Perhaps because of the wallpaper” (Gilman 6). Both characters are at first tormented by their wallpaper, but later come to enjoy it as a source of familiarity. Even though Raskolnikov commits the murder in order to escape the yellow wallpaper that suffocates him, he comes to approve of it in the end. This all seems to illuminate the madness that wallpaper truly is. For what is wallpaper but a form of masking, of hiding what is really underneath?

Dostoevsky, Feodor. Crime and Punishment. Norton Critical 3rd Ed. Translated by Jessie Coulson and edited by George Gibian. W.W. Norton & Company: 1989.

Throughout my reading of The Moonstone thus far, I find myself noticing the narrator’s voice a lot. Mostly, I find myself questioning the narrator in a lot of ways. In the margins of my book, you might find “lol,” “creepy,” “?!,” or “eye roll.” In The Moonstone particularly, I find myself noticing how Wilkie Collins has chosen these narrative voices that seem at odds with each other, but are actually quite similar in a lot of ways. Similarly, in The Yellow Wallpaper, Jane tells her own story of her psychotic episode. Thus, we have no objective accounts of the event, and in both stories we find ourselves entering into “this abominable detective business” ourselves (Collins 175). We realize that like the characters we are reading about, we share that “moral perversity” in using our snooping skills (228).

In The Yellow Wallpaper, we are constantly trying to figure out Jane’s mental stability and subsequent reliability as a narrator. For example, Jane informs us that “John is away all day, and even some nights when his cases are not serious. I am glad my case is not serious!” (Perkins Gilman). Instantly, we find ourselves questioning why John might be away so often, and wondering what sort of “cases” these are. Similarly, in The Moonstone, Mr. Betteredge feels the need to constantly re-assert his reliability as narrator, which in turn makes us doubt him. When the story transfers over to the narrative of Miss Clack, a similar effect is achieved; we know we are reading the story from the point of view of someone without omniscient knowledge.

Although the overall effect of this narrative technique can make critical reading more important, it also forces us to enter more into the story. We don’t surmise that the narrator is providing us with consistent or accurate information, and so we take to our own methods of inference to make conclusions. In both texts, the reader feels a strong connection to the events of the story because it is necessary to interact more with the text. Thus, in the case of The Yellow Wallpaper, we understand why the text resonated with so many generations. Further, in The Moonstone, we can easily understand how Wilkie Collins was such a hit success among his readers.

I have been feeling that Mr. Betteredge reminds me a lot of Mr. Carson in Downton Abbey, and in this clip I am reminded of the amount of loyalty that the servants often had with the members of the family. This is especially relevant between the relationship of Mr. Betteredge and the Varinder family, since Mr. Betteredge knew her as a child.

Downton Abbey US, A House Grieving. YouTube, 27 March 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OxB5zhH8P3c. Accessed 4 April 2017.

When I first read D. A. Miller’s The Novel and the Police, I understood what he was saying about authority and discipline because I could apply it to real life but I struggled with seeing it in the novel The Moonstone. Miller says “Disciplinary power constitutively mobilizes such a tactic of tact: it is the policing power that never passes for such, but is either invisible or visible only under cover of other, nobler or simply blander intentionalities (to educate, to cure, to produce, to defend)” (Miller 17). Reading farther into the character of Sergeant Cuff, however, and allowing oneself to step out of the point of view of Mr. Betteredge and question his opinions an reasons, it is plain that Cuff employs one of these policing powers that do not seem like they are. He does this through manipulation, particularly through playing off of other character’s pride. The best instance of this is when he is leaving the house after the investigation has apparently concluded. Betteredge has spent the entire last couple of chapters completely hating Sergeant Cuff for accusing his mistress Miss Rachel of stealing her own diamond. This is a especially sensitive accusation for Betteredge because of his affection and respect for his employers. However, the Sergeant is able to manipulate Betteredge into liking him despite this. Cuff says to him “I would take to domestic service to-morrow, Mr. Betteredge, if I had a chance of being employed along with You!” (185). By flat out flattering Betteredge, Cuff slides unseen into his good graces and in doing so is able to police him. Mr. Betteredge himself proves this by saying “I own I couldn’t help liking the Sergeant – though I hated him all the time” (186). Cuff has manipulated Betteredge to his advantage.

“They had ignorantly done something (I forget what) in the town, which barely brought them within the operation of the law. Every human institution (Justice included) will stretch a little, if you only pull it the right way.” (94)

This quote from the Moonstone seems to sum up high society, both then and now, in a nutshell. If you have the right amount of money, or the right connections, you can essentially get away with anything. The fact that this line appears in a story about something being stolen, and then (presumably) found, leading (again, presumably) to the arrest of the perpetrator, is kind of ironic. Is this not a detective story? Do those not strive to uphold, and even champion, justice and the law?

According to “Jane Eyre”, Victorians took the law pretty seriously, too; Rochester hid and secretly cared for Bertha because it was illegal to divorce an insane person back then. He had massive respect for the law and morality, as did Jane, since neither of them really pursued the potential relationship between them until Bertha was out of the picture. Even in the other books we read (“Tale of Two Cities”, most notably) the law and justice (however warped that latter ideal may end up being) were central pillars of the stories, and were pivotal in driving them forward.

So why, then, does “The Moonstone” seem to treat it with such triviality? It could be because, in this case, nearly everyone is related to high society in some way. Nearly all of our central characters have some sort of upper-class affiliation, because otherwise, how would they even know anything about the moonstone? Previously, most of our characters have either been middle-class, or lower-class (with most of them coming from the former). The law is harsher to them. It’s not as harsh to the upper class because, as the quote above states, the law will easily bend if you pull it in the right way; in other words, if you have the connections, you’re above the law.

Could this be a criticism of Victorian high society. with a pompous and arrogant statement such as this in a story that (again, presumably) ends with the triumph of the law? That seems to be the likely answer. But what if the person who stole the moonstone actually gets away with it? Then what does this quote imply? What does it mean for society’s relationship with the law? Does it strengthen it, weaken it, or invalidate it completely? I don’t know how the story ends, so I can’t really say. But what I can say is that I hope it ends with the thief getting away with it, because then “The Moonstone” and its concept of law and justice suddenly stands in a stark and very intriguing contrast to everything else we’ve read thus far.

In D.A. Miller’s book, “The Novel and the Police,” he writes, “Disciplinary power constitutively mobilizes a tactic of tact: it is the policing power that never passes for such, but is either invisible or visible only under cover of other, nobler or simply blander intentionalities (to educate, to cure, to produce, to defend)” (Miller, 17).

In Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, religion has taken the form of various entities. From Betteredge’s personal Bible, Robinson Crusoe, to the religious Rachel Verinder and her mother, all the way to the esteemed Godfrey Ablewhite and his respectable charity work (yeah, not for long), religion has manifested itself in different ways throughout the story. However, when introduced to Miss Clack, the second narrator, religion is presented in a different way. Here, we catch a glimpse of evangelical Christianity.

“Oh, Rachel! Rachel!’ I burst out. ‘Haven’t you seen yet, that my heart yearns to make a Christian out of you? Has no inner voice told you that I am trying to do for you, what I was trying to do for your dear mother when death snatched her out of my hands?’ (Collins, 269).

After the death of Lady Verinder (that made really sad, of course), Miss Clack tells Rachel that she wants to “make” her a Christian (isn’t she already a Christian?). In a way, Miss Clack feels guilty because she feels that it is her fault that she wasn’t able to “save Lady Verinder’s soul [from hellfire].” As a result, she feels that her moral duty is to spread the word of God – to use religion as a policing power – to others to prevent them from eternal damnation. Throughout her narrative, we have seen her do exactly that: force books onto others, persuade others to go to church, etc.

Nevertheless, there is something mysterious – and fallacious – about Miss Clack’s character. To be honest, I’m not even quite sure if she understands what it means to be a Christian. In chapter 1 of the second period, she says, “Let your faith be as your stockings, and your stockings as your faith. Both ever spotless, and both ready to put on at a moment’s notice!” (Collins, 204-205).

In this passage, Miss Clack relates Christianity to a stocking – an odd and unseemly comparison, if that. If Miss Clack were truly a Christian, she would argue that we are Christians all of the time. Of course, we are sinners, but we are always under God’s love and protection because we have been saved. The fact that she believes Christianity can just be “put on at moments notice” shows that she truly isn’t as pious as she seems. Instead, it seems to be a facade – a veneer that she puts on to seem superior to others. Doesn’t that make sense? Think about it: she even takes her “stocking” off at the end of chapter 5 – remember how indignant she was for not being written into Lady Verinder’s will?

While Miss Clack repeatedly uses her religion – Christianity – as a policing power to “save others” through invisible means such as words, and visible means such as books and pamphlets, she never really abides by her own rhetoric. To be honest, Lady Verinder should have been the one “policing” Miss Clack, as she seemed much more reverent and pious. Despite Miss Clack’s eccentricity (what’s a better word I can use?), I am nevertheless moved by her character. Although her understanding of Christianity seems skewed, she finds her cause (to make others Christian) noble.

In all, this novel is marked by misleading appearances and dispositions. Nevertheless, because we are dealing with a mystery, I think Collins is trying to prove a point. Because we are in the midst of a disappearance, we should keep in mind that these “misleading appearances” are marked by differences in systems of value. Similar to Miss Clack, the Indians, on the surface, seem evil and dangerous, but further down, they find their objective to return the sacred gem to India, virtuous and noble. In other words, if Miss Clack feels that she is doing the “right” thing, should we judge her (even if we don’t agree)?

In the nineteenth century, the Bronte sisters took the literary world by storm, with the release of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and her younger sister, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights.

In Wuthering Heights, the story of Catherine, Heathcliff, and the remainder of the Earnshaw and Linton families is told through a narrator finding out information from another narrator. To break that down, Lockwood is learning about the characters and their stories through Nelly, their former servant, and he is attempting to tell the story that he heard from a first-hand witness. So, basically, he is the secondary source, telling the story with some things lost in time – whether that’s Nelly’s fault for over-embellishing or his own for misinterpreting the complexity of the events.

Emily’s sister Charlotte, however, took a different approach of story-telling. In Jane Eyre, an older Jane is recounting her life. Although a fictional character, Jane’s story is being told in the form of a memoir within a story. Wuthering Heights adopts a similar style of a “story being told within a story” with the complexity of the narrators. In Wuthering Heights, I would definitely argue that Lockwood and Nelly are unreliable narrators, because they are both flawed in their story-telling, as mentioned above. Though many people wouldn’t consider Jane to be an unreliable narrator, I would argue the opposite, since her story is not being told in the present tense and as an older version of herself, her reflection and perspective of the events that happened may be more skewed than if they were told in the present tense.

Both stories are being recounted from past events, which makes for unreliable narrators, one is being told from a first-hand account, the other is being told from a second-hand account. For me, making the connections between these two novels stylistically enabled me to think about narration impacted the story-telling of each one, and whether or not having non-conventional styles affected the how I perceived the events of each story. Though different texts, the connection between the two styles of narration that the two Brontes used do have one main thing in common: they’re both stories-within-stories and frankly, can be quite complex.

In his introduction to The Novel and the Police, Miller describes how “police” refers not just to the government institutions of law enforcement, but also surveillance and discipline more generally. He describes, “To label all this ‘the police’ thus anticipates moving the question of policing out of the streets, as it were, into the closet—I mean, into the private and domestic sphere on which the very identity of the liberal subject depends” (viii-ix). What is established, then, are two separate spheres of policing, the pubic, as is demonstrated by organized police forces and similar institutions, and the private, which is made up of a more social kind of surveillance and discipline. The Moonstone demonstrates how these two spheres of policing can come to be at odds with each other through Sergeant Cuff’s interactions with the Verinder household.

Sergeant Cuff, although being specifically hired to sort out the matter of the Moonstone, is very much distrusted by various members of the household. Both Betteredge and Lady Verinder try very hard to refuse to believe Cuff could possibly be correct in his conclusion the diamond has been stolen from someone inside the house, or as it is later revealed that that Miss Rachel has possibly stolen her own diamond. Ff diamond had been stolen by an outside force, like the three Indians, who also have being radicalized others against them, perhaps Cuff would have been able to easily act as a public police force. But when he attempts to enter private household system that is already carefully policed and surveilled, and act as a police force, then he is rejected.

Cuff, however, seems to be aware of his position as an outsider and the lack of authority he maintains over this system of the home. In fact, he has worked on several occasions with externally policing “family scandals,” and knows how to negotiate within the family. He states, “I had a family scandal to deal with, which it was my business to keep within family limits. The less noise made, and the fewer strangers employed to help me, the better…I trouble [Lady Verinder] with these particulars to show you that I have kept the family secret within the family circle. I am the only outsider who knows it—and my professional existence depends on holding my tongue” (175). In order to be able to police, Cuff must relinquish his public power, and acknowledge that he is not interested in externally policing, but rather wants to act as a mediator in the pursuit of truth. There is no mentions of Rachel possibly being punished formally for her crime if she were to admit to it. Her punishment rather would likely rather be the possibility of her private crime becoming public, and the fallout of her social standing that would ensue. The private forms of policing have too much influence here, and in fact are able to potentially overcome the law.