This post examines how a biographical understanding of Javier Zamora’s life illuminates both the content and publication history of his poetry. Born in El Salvador, Zamora migrated to the United States at nine years old; his recently published and first full-length poetry collection, Unaccompanied (Copper Canyon Press 2017) describes the Salvadoran Civil War’s impact on his family, as well as his experiences with border crossings. It is evident that Zamora’s identity and experiences as a Salvadoran immigrant living in the U.S. are central to the stories he tells within his poems, on top of being crucial to his politicized motivation to write and share these stories in the first place. In addition to holding a BA from UC Berkeley and an MFA from New York University, Zamora has won numerous prestigious fellowships. Currently a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, Zamora is arguably the most institutionally well-recognized contemporary Salvadoran writer.

With poems that appear in literary spaces as prestigious as The New York Times, Poetry, and Granta, among many others, Zamora’s work has reached a prominent status by mainstream literary standards. Of the list of contemporary Salvadoran poets actively writing in the U.S. that I have identified in the last few months of research, Zamora is one of three to be featured on the Poetry Foundation website. The other two Salvadoran poets recognized by the Poetry Foundation are Christopher Soto and William Archila; although Soto and Archila’s biographies are highlighted by the Poetry Foundation, individual poems are not. On the contrary, Poetry has featured seven of Zamora’s poems and a blog post reflecting on one of his poems published by the magazine. Several of these poems, as well as others that were published elsewhere in literary journals ranging from the American Poetry Review to Huizache and Ploughshares, reappear in Zamora’s Unaccompanied.

Importantly, Zamora has not only been recognized for his individual poems or even more broadly, for his poetic prowess, but rather, it seems many major media organizations are also invested in how his presence and process as a writer is shaping current literary cultures. Featured in an article by The New York Times titled, “The Rooms Where Writers Work,” Zamora is highlighted alongside writers Camille Bordas and Danzy Senna. He is depicted via photograph in his San Rafael home, and the article features Zamora’s description his daily life, ranging from the music that inspires his work, his reading habits, to details about his writing process. This is significant because of the infrequency with which writers of color are allowed the space to discuss fundamental elements of craft and process.

In many of the interviews published online, Zamora has spoken often of his journey as a poet in constantly revising his work as he revisits the trauma of the narratives he recounts. In the aforementioned interview with The New York Times, Zamora said: “Some of the poems in my new book were the first ones I ever wrote, and I worked on them, especially the one about crossing the border, ‘‘Let Me Try Again,’’ for almost nine years.” The poem appears in the July/August 2016 edition of The Kenyon Review, in an earlier draft of the one published in Unaccompanied. Zamora’s formal changes are evident, as the poem moves from a controlled couplet structure to become a poem that is far more jarring in its scattered composition.

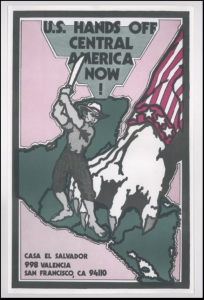

A poetry collection that also builds upon his 2011 chapbook Nueve Años Inmigrantes, Unaccompanied has recently received much attention and acclaim since its publication in September this year. Most notably is The New Yorker’s feature of his work, an article called “An Immigrant Who Crossed the Border as a Child Retraces His Journey, In Poems.” The title of the piece already evokes certain expectations for Zamora’s writing—in terms of why it matters and through what lens it should be read. Zamora’s identity as immigrant is prioritized before his identity as poet, indicating a politicized reading of his poems. This is especially interesting in considering The New Yorker as a reputable, high-caliber magazine with an audience that might generally be described as particularly invested in notions of ‘literary prestige.’ Questions that this raises for my research are: how does Zamora’s existence in prestigious literary spaces inform or complicate the way we might understand his work and, specifically, his work in the broader contexts of Salvadoran and U.S. Latinx writing? What does it mean, politically speaking, for his poetry to be recognized in the way that it has—especially in the present-day United States, under a presidency that has continued to publicly threaten Central American teenagers, in particular, with deportation?

Guadagnino, Kate. “The Room Where Writers Work.” The New York Times. 16 Aug. 2017

Paredez, Deborah. “Unaccompanied: An Interview with Javier Zamora.” Poets.org. 2 October 2017.

Zamora, Javier. Nueve Anños Inmigrantes. Organic Weapon Arts, 2011.

Zamora, Javier. Unaccompanied. Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2017. Print.