The thing that really stuck with me about Swinburne is his use of violence, gore, and social taboos in association with beauty, desire, and eroticism. I think this is most clear in “The Leper.” The body of a once beautiful woman is lusted over by her faithful scribe. It’s disturbing, but Swinburne does a wonderful job of conveying the emotions this guy is feeling. The scribe even knows that it is wrong, stating “though God always hated me / And hates me now…” (lines 14-15). He’s even glad that the girl is dead, because that is the only way he could ever have her the way he wants. The Penny Dreadful clip we watched in class conveyed this same dichotomy: the conflation of gore and violence with beauty and emotion.

NBC’s Hannibal uses a similar technique in the way they present food. The show is an adaptation of the novel The Red Dragon by Thomas Harris. It’s a prequel to the popular film Silence of the Lambs. Hannibal Lecter is a respected psychiatrist aiding an FBI crime scene investigator, Will Graham, who has an unusual empathy disorder. The show follows the complex relationship between the two, with Hannibal manipulating Will as he tries to solve increasingly disturbing crimes and unknowingly hunts for Lecter himself. The show’s creator, Bryan Fuller, was not shy with violence or gore. It’s a disturbing show in many ways, but not just because of the blood and guts. One of the most disturbing aspects of the show is the beautiful, mouthwatering food design.

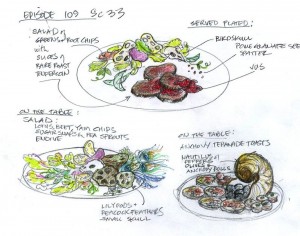

The audience knows Hannibal is a cannibal, so it’s disturbing just see the characters unknowingly eating human flesh. But its even more disturbing because it looks so appetizing. Hannibal’s dishes are always exquisite, with rich colors and precise plating, and he presents them as exotic delicacies like foie gras au torchon with figs (see picture) or flambéed lung. A quote from food stylist Janice Poon sums it up perfectly, “My wish is that the food looks so creepy, and so foreboding and so menacing, but appetizing.”

These beautiful meals are reflective of Hannibal himself. He’s almost always dressed in immaculate three-piece suits, always unruffled and emotionless. He sees himself above everyone he interacts with, an all-powerful god playing with people like toys. But as the audience knows, this perfectly composed wardrobe and attitude hide a sinister villain. Hannibal is just like his dishes––creepy and foreboding, but perfectly polished and elegant.

As I mentioned, this is a very bloody and violent show. Hannibal Lecter is not the only villain. Will Graham investigates the most disturbing murders imaginable––from a human totem pole to human cellos to a human fungus garden. It’s not pretty (don’t look up pictures if you’re faint of heart) except that it is. Even if they’re more immediately gross, each crime scene is perfectly laid out just like Hannibal’s meals and suits.

As a viewer you sort of become accustomed to the level of carnage. Each gory shot is set up meticulously. As a result, every other shot becomes suspect. A close up of something perfectly normal, like a cup of coffee or a blooming flower or a fishing lure, becomes disturbing by association. The “deluge of words” that Swinburne uses to overwhelm his readers reminded me of this. The coupling of sensations like disgust and revulsion with fascination and beauty and aesthetic appeal permeates every scene in Hannibal, even when there is no body in sight. Most things are not as they appear––Hannibal’s beautiful meals, his suits, Hannibal himself. So when something really is just a cup of coffee or a flower or a fishing lure, you’re not really sure anymore.

Examples of Hannibal’s meals: http://www.vulture.com/2014/03/see-every-food-porn-shot-from-nbc-hannibal/slideshow/

Examples of the cinematography (Warning: this one contains images of some of the crime scenes): http://www.buzzfeed.com/danieldalton/i-gave-you-a-rare-gift#.tyORWJkv4

Quote from Janice Poon is from this article: http://www.buzzfeed.com/emofly/hannibal-food-secrets-janice-poon#.pdMlxBYZJ