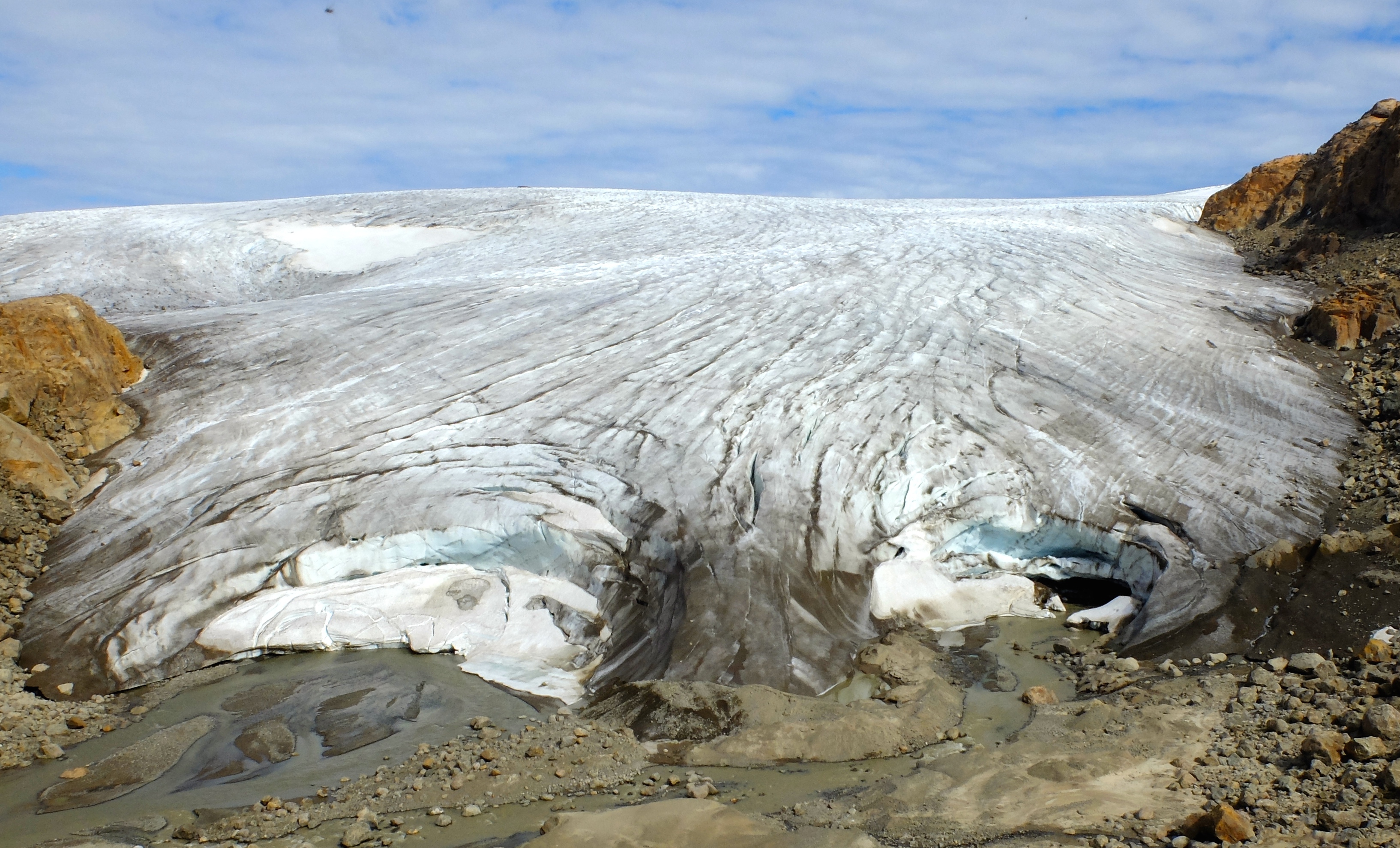

Sunday: I spent the evening snuggled up in bed watching James Balog’s documentary Chasing Ice on Netflix. Before watching, my expectation for the documentary was that it was going to be one of those “facts-down-your-throat” documentaries, but I was pleasantly surprised. First of all, the film was highly artistic due to the stunning way the film captured ice. Equally as gripping was the storyline behind the Extreme Ice Project in which Balog deals with camera issues, family pressures, knee surgeries and life-risking ice photos. The photos powerfully depict the story of the individual glaciers demise and the diagrams interjected into the film highlight why these melted glaciers indicate climate change. These photos that Balog (at times) risked his life to photograph are effective mechanisms of documenting climate change.

Monday: James Balog came to my Introduction to Soil’s class where my five classmates and I were able to openly ask him questions. The class began with my professor, Ben Edwards, a volcanologist, presenting his current research to Baloag. He is researching the interactions between lava and ice which he demonstrated in his youtube video of lava being poured on ice. This captivated Balog due to his love of ice and wanted to learn more.[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fcz3vBdI7Nc” title=”Ben%20Edward%27s%20Lava+%20Ice%20Research”]

We then continued to bombard Balog with questions, ranging from: What school did you go to? – Why did you decide to be a photographer? – What job advice can you give us? I wanted to ask him a question of my own so I asked him if he ever took photos of indigenous groups and the changes to their society. He said he focused on glaciers and the people affected by glaciers were outside his realm of expertise. Although, lava and ice don’t exactly fall under the soil class’s syllabus, it was really interesting to spend the class talking with Balog.

Tuesday: This time Balog came to a more appropriate class, our sustainability mosaic course. Interestingly enough the questions and conversation were very different from the previous day. Although there were questions about his personal life, the conversation was directed towards climate change and his film. One overall message that I will remember was when Balog said something along the lines of: he cannot tell us what to do about climate change, but he can encourage each of us to find a voice and way of expressing our concerns. After a group photo and a selfie, we waved Balog good-bye with a lingering awe.

At 7pm, we attended his two- hour lecture that was focused on science and art components. I found the science part highly interesting for he presented interesting figures and evidence concerning climate change. In the art section of the lecture, he used poetry, music and photos he created a voice regarding climate change’s effect on glaciers that had never been done before.

Wednesday – Friday : After his presence at Dickinson College, there was a mull of student discussion about his unique talk and breath-taking documentary. Whenever I was in the Library, I would get captivated by his glacier photo display and I would convince anyone who would listen to watch Chasing Ice. I was impacted by the multiple meetings with James Balog throughout the week and I was really glad that Dickinson was able to create this opportunity.