Nine Days in Havana

Many thought they would never have a chance to travel to the elusive island of Cuba, separated by a mere 90 miles but a huge gap in understanding. For many students and professors alike, Cuba was a topic of interest and study but an intangible goal, a “forbidden fruit” as one student described it. When the Community Studies Center advertised the Cuba: Social, Economic, and Environmental Sustainability and Resiliency course in the fall, the response was overwhelming. In the end, sixteen lucky students and five professors and associates formed the Dickinson delegation boarding a small charter flight headed for Cuba on March 10, 2012.

Prior to their departure and throughout nine days in Cuba, students focused on a wide variety of topics associated with Cuban society, politics, and culture. Latin American and Caribbean Studies majors joined Environmental Studies majors in reading about urban agriculture. History majors discussed issues of sexuality and gender equality with Sociology majors while Women and Gender Studies majors read about medicine and socialism. The wide array of topics covered helped prepare students for the seemingly new world they would experience when they stepped down from the airplane into the bright Caribbean sunshine. During the nine days, prior classroom experience and readings came to life with lectures and trips to the National Center for Sexual Education (CENESEX), an organopónico and other urban agricultural sites, the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), and numerous musical and cultural events, including concerts by Tony Avila and Silvio Rodriguez. Lectures were carefully yet dramatically translated by our amazing interpreter, Alberto Gonzalez. Esteban maneuvered our large and colorful bus expertly through the streets of Havana while our charming and adept guide, Carmen from the Martin Luther King Center, led us on to our next event.

Other members of the Dickinson community who had previously done research in Cuba were able to share their research and work throughout the week as well. Professor of economics Sinan Koont shared his knowledge of urban agriculture and his book Sustainable Urban Agriculture in Cuba, while Steve Brouwer accompanied the group to ELAM where he was able to give his book, Revolutionary Doctors: How Cuba And Venezuela Are Changing the World’s Conception of Health Care, to current ELAM students and faculty he had previously interviewed. Dickinson’s photographer, Carl Socolow ‘77, displayed his inspirational photography to fellow Dickinsonians and Cubans alike at Centro Pablo de La Torriente Brau’s exhibit of his work Mata Ortiz: vida cotidiana.

As a member of the Dickinson delegation to Cuba, I feel incredibly lucky to have been given the opportunity to travel to a country that is so close and yet so far from our own. We were able to see the vibrant lives of Cubans and comprehend an alternative and complex system of values and ideals during our stay, a system that fosters a different meaning of quality of life than we are accustomed to in the United States. Deep reflection on the lives we live and on the true meaning of solidarity accompanied us all the way back from the beautiful beaches of Varadero and cobbled streets of Havana to the limestone buildings of Dickinson. – Rachel

Day 1: Saturday, March 10th, 2012

Our alarm went off at 7am and Dickinson students began to fill the breakfast room of Miami’s Holiday Inn Express. As we all prepared to take the shuttle to the airport, the reality set in; we were going to Cuba. Once at the airport, we all received our travel visas and we made our way to the gate. Ironically, our gate, D60, provided a sign of Cuba-US relations, as it was all the way at the end of the airport and out of the way of the rest of the international departures. We eventually arrived at Cuba’s José Martí International Airport and proceeded to go through customs and immigration.

To eliminate any fines from the United States government and to make travel easy for American tourists, Cuba usually never stamps US passports, even for those who are visiting legally. Although some of us asked for a stamp of entry as our first souvenir from the island, the Cubans were reluctant to do so.

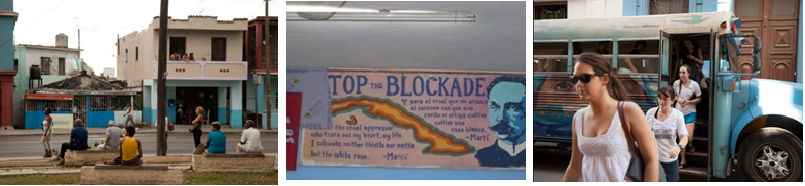

As we got our bags and walked out of the airport, a large group of Cuban citizens were waiting for friends and relatives arriving from the United States. We witnessed multiple families being reunited after what appeared to be years apart. Tears and hugs were shared all around us as we made our way to the exchange house to trade US dollars for CUC, the more valuable of the Cuba’s dual currency system. We spent a short time taking in the billboards about the Revolution that surrounded the airport and eventually met up with our guides and the “wawa” bus, our transportation for the week. Carmen (our tour guide), Esteban (our driver), and Alberto (our translator) all welcomed us to Cuba and took us to the Centro Martin Luther King (CMLK) in Marianao, located about twenty minutes outside of Havana Vieja.

On our way to the center, we got our first taste of what Cuba was really like; not just socialism, old cars, Castro’s beard, and the missile crisis. We were seeing what everyday life was like. Driving down the sometimes unevenly paved streets, the sights and smells of thick diesel fumes were a constant presence, along with images of revolutionary heroes painted on the majority of blank walls.

It seemed as though the houses and streets were literally dropped into a luscious jungle landscape as green plants and trees were always in sight. Shops and markets dotted the sidewalks, which were full of people of all ages. Once at the center, we got acquainted with our rooms and unpacked our bags. After two days of traveling, a light snack of fruit and bread was a welcomed sight, as prepared by the generous kitchen staff.

After a quick bite to eat, we were back on the bus on our way to Tun Tún Piano Bar where Tony Ávila and his band were performing for a small, intimate crowd of Cubans. We entered the dark bar to the smell of cigar smoke, clinking glasses, and loud conversations. After having our first taste of Cuba Libres (rum and coke) and fresh mojitos, the show began.

As a trovador, Tony Avila’s songs contain lyrics that have deep and elaborate meanings and refer to all aspects of Cuban culture and history, as well as relationships and everyday problems. Specifically in this performance, he sang about humor, political ties, and gender relations. One of his lyrics about politics read, “you can stay or you can go, it doesn’t matter to us” and a song about gender referred to the male-female relationship as a puppet show.

After the show was over, we left for a dinner at a paladar, or privately owned restaurant, named Honda de David (David’s Sling) in Havana. Until a few years ago, this would not have been possible due to the restrictions on private business and non-state employment. However, with the easing of these restrictions, small family-run restaurants have become very popular and widespread. After a French-style meal, we headed back for the Centro and a well-deserved night’s sleep. -Joe and Zach

Day 2: Sunday, March 11th

After the exhaustion of traveling over the course of two days, we were immediately oriented into the program in Cuba. We had breakfast at the Center, and then moved onto the roof (which doubles as the laundromat) to be introduced to the history and functions of Centro Martin Luther King. CMLK is an organization funded by the government to promote religious plurality and increase the presence of religious leaders in Havana. The organization began, and continues to be associated, with the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and their mission is to promote post-Revolutionary values amongst the Cuban population. The introduction showed us that religious values do not necessarily contradict the Socialist ideology, and that the two could not only coexist but also interact in a mutually beneficial manner.

After the rooftop chat, we chose to visit Hemingway’s house where, according to Alberto (we think), the author penned his last book (not sure if that was a joke, but let’s go with it). Hemingway’s house was located on a tree-covered hill overlooking a skyline view of Havana. The house itself was preserved with artifacts from the author’s life, including animals he had killed (apparently PETA hasn’t visited Cuba), his alcohol collection, and various publications from the mid-twentieth century. The most intriguing and hilarious part of the house was, interestingly, Hemingway’s bathroom, where he kept an extensive hand-written tally of his fluctuating weight. After taking a quick group photo, we headed back to the Center for lunch and a discussion of Afro-Caribbean religion in Cuba.

The talk covered the importation of slaves and their respective religions, followed by the integration of that culture after their emancipation. The resulting religion is a combination of regional practices, now referred to as Santería. Within Santería, the body is a central theme; sensuality and sexuality are not seen as sins, but rather pleasure is considered to be positive. The themes from the various African religions have blended into Cuban culture, and elements of Santería can be seen in everyday life. Even though Santería and Afro-Caribbean religions had been oppressed or banned during certain periods in Cuban history, its impacts on Cuban culture remain even today.

After the lecture we were driven (on our very flamboyant bus) to Hamel Alley, where artist Salvador González Escalona had introduced Santería and religion to popular art and created a small art community. The whole street was covered in colorful symbols and deities (Orishas) of Santería, some of which were explained to us by a tour guide. We walked inside Escalona’s gallery, where he continues to work and create art, and then went outside to see an Afro-Caribbean dance exhibition.

Despite the intrigue of the artwork and culture on the surrounding alleyway, the dance demonstration was, in a word, terrifying. As we had been told that the weekly rumba festival had disbanded for the day, we knew the exhibition was intended explicitly for tourists. The music supported the movements of dancers meant to represent four Orishas; though the exhibition was energetic and interesting to watch, some of us narrowly escaped death by dull machete, and one girl was burned by a cigar. Though the dance presented some amount of legitimate culture, it felt more as if we had collectively wandered into an aggressive tourist trap.

We returned to the Center for dinner, and then headed out to a concert by renowned musician Silvio Rodriguez.

We watched the concert for about an hour, and then wandered off to explore Old Havana. We were called into a restaurant, where we walked up roughly 3,000 flights of stairs (estimate) to a small, renovated apartment which held no more than five tables. Our very friendly waiter, Lanny (yup, that’s a real name), who also spoke English, invited us up onto the roof of the building. We took a few photos and admired Havana’s nighttime skyline. Lanny tried to talk us into salsa dancing, but as Americans we were culturally unaware of how to do that. After saying goodbye, we headed back to the square and caught the end of the concert. We had been instructed to return to the bus within fifteen minutes of the end of the concert, but after some deliberation we opted to stay out and wander through the city. Old Havana looks straight out of Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights, and it was somewhat difficult to figure out where to go at night. We wound up at Plaza Vieja which was clearly geared towards tourists but which was also a refreshing change in architecture after the residential surroundings of Marianao. We took taxis back, and went to sleep in anticipation of the next day. – Megan and Sara

Day 3: Monday, March 12

We awoke and were treated to a typical Martin Luther King Center breakfast. Bread, coffee, Cuban cornflakes, fresh fruit, strawberry jelly and butter so delicious and yellow it must have been homemade. Our first activity of the day, besides embarking on the tedious journey of rounding the entire group onto the bus, was a trip to the Center of Marine Biology of the University of Havana. Prior to the scheduled lecture, we heard from the director of the center, who told us about the research they conduct. Some of the work they do involves baseline testing of coastal waters for use in the case of issues associated with oil drilling and spills, as well as monitoring the health of fish populations and coral reefs. Then Professor Elena Díaz, sociologist at the University of Havana, gave a talk detailing the past and current social reforms, from land reforms and housing issues to the current economic and demographic situation.

After a discussion of Cuba’s stance on women’s reproductive rights we were very interested to hear the professor mentioned a proposed plan by the government to provide economic incentives for women to have children in order to change the demographics of an aging population in Cuba. (By 2035, Cuba will be the most aged country in Latin America due to their low fertility rate, high life expectancy, and migration). This sparked interest in reflecting on how social policies reflect cultural values, and how they both interact with the economy.

For lunch we met up with a group of current University of Havana students from different fields of study. Most of the Cuban students where in their third year and about two or the three in their fifth and final year. At our table we had the opportunity to sit with Humberto, a third year history major, Dayma, a third year communications major, and Isabel, a fifth year sociology major. Marilyn, being a native Spanish speaker, replaced Alberto during lunch, translating when needed to help the conversation keep to flowing. In discussing their schedule as university students, Humberto explained that he had already completed his one-year of military service before starting college. He now attends university full time, with classes Monday through Friday. On the other hand, Dayma works the entire week and attends classes all day long on Saturday. With Marilyn translating, Matt had a very labored conversation with Humberto about advanced historical theories, given that both were history majors. From this discussion we learned a little bit about how thorough and advanced the Cuban education system is, especially in the field of history. We discussed Fukiyama and the Hegelian theory of history as it relates to Marx in Cuba. Humberto said that before a history student picks a concentration in their third year, they must first take specialty classes in the history of each region of the world. We were also surprised to hear to what extent the Cuban students were aware and up to date in American pop culture when discussing movies and music. When we started to discuss healthcare in Cuba, Humberto asked us if we had seen Michael Moore’s latest documentary Sicko. To our embarrassment, none of us had. We ended the lunch with Humberto telling us a great quote that put a lot of things about the oppression we had been learning about, about socialism, about U.S. Cuban Relations, and even about all of our own problems in the United States into perspective. He said, “No hay mal que dure cien años ni cuerpo que lo resista” or “there is no evil that lasts a hundred years or body that endures it.”

Our next stop of the day was ELAM, the Latin American School of Medicine. Within this school, Cuba houses the ideology that constitutes its biggest industry, trained and willing doctors ready to go oversees, sometimes as humanitarians and sometimes as doctor mercenaries, to improve public health in impoverished communities. Apart from their own students, Cuba also trains young adults from 96 different countries, totally free of charge, in hopes that they will return to their own communities to practice medicine. Here we had coffee and a brief conversation with the dozen or so American students training there to become doctors. From what we heard, the American students were much older than the average first year (Cubans and students from other developing countries generally enter the program around 16 or 17 while most of the Americans have already finished undergraduate studies and in some cases had spent a few years already in the job market). All of these students will graduate with a degree in general medicine and after passing the licensing test will be totally certified to practice in the United States or stay on at ELAM to continue with a specialty. It once again drove home the message of sharing. These doctors plan to go on to share their skills and expertise with the world’s most impoverished communities, often for average pay.

After dinner we attended a wonderful and entertaining lecture on the theoretical and philosophical systems of oppression, liberation, and colonialism at CMLK. We got some great quotes out of it and the lecturer seemed like one of the more eccentric academics we met while in Cuba. We ended the evening as we ended many evenings in Cuba, listening to a live band play Cuban music with a mojito in one hand and a cigar in the other. It was a very long day. – Matt and Marilyn

Day 4: Tuesday, March 13

“What has Cuba done for the environment? Urban agriculture.”

We woke up early in order to maximize our time at the UBPC (Basic Unit of Cooperative Production) Organopónico Vivero Alamar, a 28-acre organic garden in Havana founded in 1997. For those of us who are avid followers of our professor, Sinan Koont, economist and Cuban urban agriculture enthusiast and author, this was the moment for which we had been waiting. We like to think everyone else was just as thrilled when we arrived at Alamar and took in its sheer magnificence, a green wonderland of sorts, with fruit trees, ornamental plants, and vegetables at almost every stage of growth. It had started to rain as soon as we got to the farm, filling us with dread that we wouldn’t be able to film or work in the fields. Thankfully, the rain held off when we were ready to embark on our tour.

Cuba truly has organic urban agriculture down to a science. In their Manual Técnico, they have recommended mixtures for potting mix and cantero (raised bed) substratum, utilizing compost (decomposed organic matter), worm humus (a rich soil-like material produced from the digestion of organic material by earthworms), rice hulls (a byproduct of rice production), and mycorrhizal fungi (which attaches to a plants’ roots and facilitates water and nutrient uptake). We heard from Medardo Naranjo Valdés, our tour guide and the Technical Director, about these various technical aspects, like the biological pest management and the sources of soil fertilization. The semi-protected greenhouses (above), covered by watertight mesh, protect the plants from pests while maintaining airflow and adequate temperatures.

The impression we had from reading Professor Koont’s Sustainable Urban Agriculture in Cuba came to life as we continued our tour. The organopónico (raised beds surrounded by walls and filled with soils amended with organic material) section was quite impressive not only in its extreme precision, but also in imagining the vest amounts of forthcoming food that will soon be harvested from these beds as the transplants continue to grow.

During the tour, we saw many different aspects of sustainable agriculture being put into practice. The UBPC was more than just ecologically sustainable due to the organic practices and lack of synthetic inputs, but felt socially sustainable as well. Both men and women were employed on site, and signs were hung on the walls of the eating area addressing issues of gender equality. People were simultaneously earning a living wage, gaining technical skills, and gaining access to fresh, nutritious produce.

A student from Haiti was working at the farm as well, focusing on the production of value-added goods such as dried herbs and spices and preserves. Two workers were making tomato sauce out of recently harvested tomatoes. On the other side of the farm, which we weren’t able to see, a program for raising ganadería (livestock) was in its infancy.

After the tour, half of the group remained at Alamar in order to work in the fields. We had the privilege to transplant lettuce seedlings in the huerto intensivo (similar to organopónico, but without walls) section. We spoke to some of the workers, most notably with Jairo, a university student from Colombia who was working at Alamar and attending school in Havana. He came from an organically run family cattle operation at home producing milk and beef. He told us about his interest in and commitment to the ideals of organic practices, which were clearly embodied in the work done at Alamar. Jairo also oversaw us as we transplanted the lettuce; he did it with such ease and efficiency that we felt foolish fumbling to plant the delicate seedlings.

We also got to eat lunch at the farm, which was cooked on site using some of the vegetables from the fields. We were not the only Americans at lunch, however. We were joined by a group of older tourists visiting Cuba who seemed to have gotten little briefing on urban agriculture before the trip. We chatted with them for a bit while enjoying a hearty meal of rice, beans, a small portion of ground meat and diced potatoes, and a light salad.

After the rejuvenating lunch, some of us even got to interview Miguel Salcines, founder and director of Alamar. He is an extremely busy person, so we were very appreciative of his time and hearing about his passion for agroecology. Mr. Salcines was down to earth and funny, as he requested 50% of the profits from the short documentary on Cuban urban agriculture that a couple of us plan to do for our final project. We shook on it.

Our time later in the afternoon was limited in terms of doing much productive work on the farm, but we did get a chance to sample some of their products. In addition to raising vegetables for sale to members of the cooperative and people who buy directly from the UBPC, Vivero Alamar sells freshly made sugarcane juice, called guarapo, directly on the street. Miguel took us to the stand and bought us all sugarcane juice to try. It was delicious, but almost sickly sweet. The sugarcane juice stand was located right next to the vegetable stand used for direct sale. We talked to a few people buying directly from the stand and watched as they took vegetables home. They told us that they were pleased with the vegetables from the organopónico and happy to speak to Americans. This desire to interact with Americans was a sentiment that continued throughout the trip.

We then returned to the CMLK for a lecture by Jesús Figueredo of the Center on food sovereignty. He presented this concept as localized management, or being able to think, “What do I have available here first?” in terms of food and other resources before resorting to importation. As (North) Americans, we have a difficult time thinking like this, mostly due to our globalized paradigm. On the other hand, Cuba was forced to adopt this mindset during the Special Period. Jesús eloquently stated that in the absence of the blockade, Cuba would be “better, but worse,” in terms of the increased availability of vital resources versus the potential to rely completely on oil once again. With the blockade, he said, Cuba is worse off but striving to be better in terms of the peoples’ adaptability and resilience, especially in the case of urban agriculture. He implied that if the blockade were lifted, Cuba might be tempted to go back to the intensive use of petroleum-based fertilizers and pesticides. This was the case before the Special Period, a time when the Soviet Union and their industrialized farming methods had a strong influence in Cuba.

Later that evening, we were able to eat dinner at another paladar called Diago. (Paladars are private, family-run restaurants of Cuba that have recently been permitted by the government in the quest for economic reform). This one in particular was in the home of Raúl Diago Izquierdo, a retired Cuban volleyball player and three-time Olympian. He was very decorated by the end of his career, and showed us a number of his trophies inside the house before we sat down. The other medals were displayed behind the bar. We had a delicious five-course meal, all the while reflecting on the fact that the majority of Cubans would be unlikely to eat at such a place, where our meals cost about 10-15 CUC per person (roughly equivalent to 10-15 USD).

We were also lucky to be joined by Conner Gorry, an American journalist. She has been living in Cuba for the past ten years after she fell in love with a Cuban, living here as a resident journalist chronicling medicine and health care in Cuba with the MEDICC Review. She said to us that Americans come here and write under the wrong context. She revealed a simple illustration of this: with the outsider’s context, one may think, “Wow, there are so many old cars!” when the Cuban sentiment is, “Wow, there are so many new cars!” She described the extremely negative impacts of the embargo on medicine availability for Cuba, which actually negatively benefits the U.S. because Cuba has developed some medical vaccines that the U.S. can’t use, such as for meningitis (a common issue on college campuses like our own). Conner explained how she rides a bike and lives without a cell phone, all the while smoking a cigar. She seems very happy with her life here. She believes that free healthcare is the way to go, as well as community family doctors. We enjoyed hearing her insights, and slept well from our full bellies and our day in the fields…the fields of the city, that is. -Anna, Jordan and Rachel

This afternoon about half our group went to OAR, an NGO that strives to educate about gender violence and provides services for victims of domestic violence. We walked to the organization from the MLK center—just a few blocks through a residential area. The building was humble, as were the women who greeted us. Dressed casually, pamphlets serving as fans as their only defense against the heat, the women welcomed the ten or so of us in to sit on plastic chairs arranged facing a large screen pulled down from the ceiling. I knew the hour or so ahead of us would be one of the more somber meetings we would have that week. Professor Rose helped lighten the mood, though… anyone who was there knows what I’m talking about!! After a good laugh, we resumed introductions, translated in English and Spanish. Two women in particular caught my attention when they introduced themselves as representatives from the Federation of Cuban Women. The Federation of Cuban Women is one of two groups about whom I am writing my senior thesis paper, so I instantly began thinking about what I might want to ask these women if I had the chance after the presentation. The Federation of Cuban Women, they explained in their introduction, represent the women of Cuba and form part of the decision making process at OAR, backing up OAR’s efforts in any way possible.

After introductions we watched a short film that one of the women had produced. The film had images of a woman in distress, with a voiceover telling her story of suffering psychological and physical abuse at the hands of her husband. Ultimately, she shot and killed her husband to escape his abuse. This film served to start a dialogue about gender violence in Cuba. More than anything, I was struck by how similar the dynamics are in the United States and Cuba. In both countries, women are often blamed for their own victimhood. In both countries, a woman who kills her abusive husband may be penalized more than an abusive husband who kills his wife. In both countries, a larger cultural issue of patriarchy or machismo perpetuates a normalization and acceptance of gender violence.

After the presentation, I was able to speak with the women from the Federation of Cuban Women. Shout out to Megan and Marilyn for translating for me! They told me that they work as leaders at the municipal level, and that while their work is paid, it is also deeply rewarding on a personal level. I gathered that most of their work centers on women’s empowerment and education—providing the necessary resources to function in a variety of circumstances.

Though only for a short time, I feel fortunate to have had the chance to speak about these issues in Cuba, something I have done much of in the United States. Having this dialogue in a new space, with new people helped refresh my perspective and made me realize that work is being done in many places and in many ways. – Ana

Day 5: Wednesday, March 14

Throughout our five days in Cuba so far, we have heard a great deal about solidarity and unity as the foundation of the revolutionary spirit in Cuba. According to the lectures we have attended and the people we have met so far, Cubans act and think according to not only what is best for the community but what will further their revolutionary goals. From what I have observed, Cubans take pride in living out the revolutionary ideals of unity and solidarity in their everyday lives.

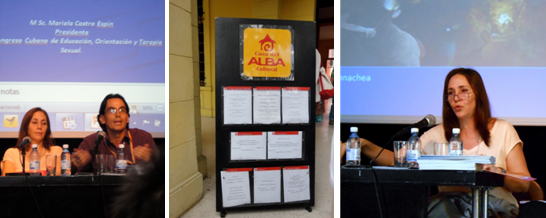

Today, the lectures and presentations we attended demonstrated two distinctive ways in which Cubans navigate the relationship between diversity and unity. As a “norteamericana” this relationship challenged my understanding that individuality and solidarity were pretty much antonyms of one another that are very difficult to reconcile. All three presentations by Raúl Suarez, Mariela Castro Espín, and Manuel Vasquez Serjido touched on the idea that diversity is not only important to Cuban equality, but helped further the revolutionary ideals and socialism.

Our morning started off bright and early with a meeting with Reverend Raúl Suarez, the founder of the Centro Memorial Martin Luther King , the organization that is hosting us during our time in Cuba. Raúl Suarez is a Baptist Reverend and member of the Cuban National Assembly. Reverend Suarez spoke to us about the diversity of religion in Cuba and the difficult relationship between organized religion and the revolution. Nevertheless, Reverend Suarez’s experience with the Baptist Church in Cuba has been completely intertwined with the revolutionary movement, even saying that he became involved in the July 26th Movement after being inspired by his instructors. I believe Reverend Suarez’s overarching message was that despite their apparent religious differences, all Cubans are granted equality and should therefore work together to maintain socialism in Cuba. Through Reverend Raúl Suarez’s presentation, we learned about the relationship between religious diversity and national unity.

After meeting with Reverend Suarez, a group of about twelve students and faculty from Dickinson headed over to the Casa del Alba Cultural de La Habana to attend the panel discussion entitled “Género y la diversidad sexual” (Gender and sexual diversity). The most memorable part of this particular panel was the presentation by Marliela Castro Espín, the director of El Centro Nacional de Educación Sexual (CENESEX) and the daughter of Raúl Castro, Cuba’s President. Mariela Castro provided an informative background about sexual education and social progress in Cuba. She spoke about focusing on the diversity of women and sexual identities in CENESEX’s national campaigns. For example, while I am used to speaking about LGBT issues, CENESEX makes sure to include intersexuals and heterosexuals into the acronym (making it LGBTIH) to address both the needs of a more diverse group and to create solidarity. It was a privilege to hear Mariela Castro speak and to hear directly from her about the programs and initiatives that CENESEX is working on. This panel discussion also allowed us to learn about the relationship between sexual diversity and Cuban solidarity.

Following lunch at the Martin Luther King Center, the entire Dickinson delegation visited CENESEX. This center is the national organization for sex education and is part of the Ministry of Public Health. CENESEX creates and implements the national program for sex education throughout each and every educational level throughout the country. Along with sex ed, CENESEX handles issues related to gender violence and LGBT rights. Manuel Vazeuez Serjido, the employee who presented to our group works in the legal advisory department of the organization. Our visit to CENESEX showed how an organization within a government that is based on socialism and unity is navigating the complexity of gender and sexual diversity. Towards the end of his presentation, Manuel Vazeuez Serjido said “We are all equal because we are different” which struck me as a great quote that summarizes this relationship I had been thinking about throughout the day.

I learned a great deal through our time spent with Reverend Suarez, Mariela Castro, and at CENESEX about the important relationship between religious and sexual diversity and solidarity in Cuba. These presentations gave me some new points of view on how to view religion and sexuality within a larger social context. -Arielle

On Wednesday we had a full day packed with talks and lectures on religion, the Cuban economy, sexual education and urban agriculture in Cuba. Right after breakfast we talked with the director of the Martin Luther King Center, Reverend Raúl Suarez. He talked about the history of religion in Cuba and his personal story of finding religion in the midst of the revolution. Before 1902, the Protestant Church in Cuba was associated with Cubans and the Catholic Church was associated with the Spanish. Afterwards, however, the Protestant Church was associated with America and lost some favor in Cuba. He was born in 1935 to agricultural workers. He was in seminary during the revolution and joined the July 26th movement by transporting fliers to his hometown. After he finished his talk, he lead us in a circle holding hands and talked about how Cubans and Americans should be able to hold hands more often.

Later that morning, we headed to FLACSO for a talk on the Cuban economy by Dr. Eugenio Espinosa. I enjoyed this talk, although I knew an overview of the material from what we had learned in class. Dr. Espinosa discussed Cuba’s dependency on foreign economies before the collapse of the Soviet Union and COMECON, when they lost imports and export markets. Then, he switched to post-USSR and the shifts in the Cuban economy today. Currently, 70 percent of Cuba’s energy supply is from domestic sources, compared to the heavy reliance n foreign oil before the Special Period. Tourism and human resources are now two of the largest exports of Cuba. Technical assistance has passed tourism in the last five years in foreign income to Cuba. Interestingly, Cuba has the highest nickel reserve in the world, and the price of nickel has increased with the latest recession. Cuba is making progress towards boosting economic development and allowing for private activity, like some of the private restaurants we visited during our stay.

After lunch we headed to CENESEX (Centro National de Educación Sexual) for a talk about what the center does and what some of their programs are. Mariela Castro, Raúl Castro’s daughter, directs the center. The majority of the education they do is with extracurricular activities in schools. The center runs many different programs. I was struck by how many things they are responsible for: education, counseling, and health care. It was interesting to see how they went about their programs because it is a state run center. They promote spaces and events for the LGBTQ population, as well as the anti-homophobia day. We got a lot of information while we were there, including information on the free sexual-reassignment surgery provided by the state.

After leaving CENESEX, we took the bus to a project on green roofs. This was a neighborhood project to start a garden with vegetables, fruits, and flowers on top of a roof. We climbed up the rickety staircase to see the garden, and the roof was filled with plants and trees. There were pomegranate, lime, sweet potato, tomato and all sorts of other plants that I could not identify. They even had empty cages for raising rabbits. I was struck by how organized and space efficient the garden was, and how much it was producing. I think that it serves as a great model for other rooftop gardens, as well as urban gardens in general. We got on the bus again and drove to an organiponico, but it was closed, so we could only peer in form the outside. This was the first organiponico in Cuba, founded in 1992 by a general who worked across the street and came up with an idea for using the empty lot. What an interesting response to food security!

After dinner, we were dropped off in central Havana and wandered around the city at night. It was an interesting way to talk to locals and get a feel for the city after hearing people talk about it during the day.

Day 6: Thursday, March 15

Today we had the leisure of sleeping in a bit more than previous mornings and had breakfast at the Martin Luther King Center. After eating we jumped on the bus and made our way down through Havana, everyone looking at the window, still completely absorbed by the vibrant streets and activity happening around us.

The bus took us along the iconic Malecón and dropped us off in Habana Vieja and we walked through the colorful streets of Habana Vieja to the Centro Cultural Pablo de la Torriente Brau where Victor Casaus, the director of the center, greeted us. The center is an independent cultural institution that aims to promote local artists and expression of Cuban art, literature and music.

Victor is a warm, welcoming, intelligent man who came to Dickinson this past fall to take part in La Semana Poética (Poetry Week), an annual event that celebrates international poetry and invites poets from around the world to share their pieces with Dickinson College students, faculty and the Carlisle community. He also visited classes and talked with students about the Pablo de la Torriente Brau Center.

While at Centro Pablo, we had the opportunity to listen to Hedelberto Lopez Blanch speak. Blanch works as a journalist in Havana, and has written several books. He recently came to Dickinson to discuss the image of the United States from a Latin-American perspective. (The audio can be found on the Dickinson website here). Hedelberto told us about his work writing for Rebelión, as well as about some of the books he has written. His interests lie in Cuba-U.S. relations, the medical profession and Cuban doctors, and Cuban relations with African countries. Book titles by Blanch include: La Emigración cubana en EE.UU. (Cuban Immigration in the United States), Miami: Dinero sucio (Miami: Dirty Money), and Historias Secretas de Médicos Cubanos en África (Secret Stories of Cuban Medics in Africa).

During a lunch break at the Centro Pablo we, the faculty, and a few people from the Centro, including Victor Casaus ate at a lively government owned restaurant/brewery on Plaza Vieja in Old Havana while enjoying the music of a traditional Cuban salsa band performing there.

After lunch we had the opportunity to explore the beautiful colonial streets of Old Havana. A few students took this time to visit the large artisan market near the Malecón. The artisan market was in a huge warehouse and seemed even more expansive inside; the middle of the building was filled with rows and rows of tiny shop setups surrounded by makeshift walls displaying art work for sale. While most of the articles being sold were typical touristy things like Che and Cuban flag memorabilia there were a fair share of original art work being sold.

All the things being sold at this market were sold in CUC, Cuban’s secondary currency with a 1 to 1 ratio with the dollar, created to stimulate Cuban economy. Through conversations with local Cubans we gathered that there has been a lot of criticism surrounding this dual currency. It has led to greater stratification of the classes between those who work in tourism and can get access to CUCs and dollars and those who must continue to use the Cuban peso. This became strikingly apparent at the market. While almost most of the experience in Cuba has been inspirational in terms revolutionary thought and dialogue and constant examples of solidarity, the market for me was a separate entity from all this. It was a capitalist hubbub in a functioning socialist state.

All the things being sold at this market were sold in CUC, Cuban’s secondary currency with a 1 to 1 ratio with the dollar, created to stimulate Cuban economy. Through conversations with local Cubans we gathered that there has been a lot of criticism surrounding this dual currency. It has led to greater stratification of the classes between those who work in tourism and can get access to CUCs and dollars and those who must continue to use the Cuban peso. This became strikingly apparent at the market. While almost most of the experience in Cuba has been inspirational in terms revolutionary thought and dialogue and constant examples of solidarity, the market for me was a separate entity from all this. It was a capitalist hubbub in a functioning socialist state.

As I walked around the market with only three CUC in my hand, I asked a woman how much a small painting cost. She replied 20 CUC. Twenty CUC is about a month’s worth of salary in Cuba. I smiled and honestly said that I don’t even have that much with me. When she asked me where I was from, I said the United States and she angrily retorted “But your standard of living is much higher!” Discouraged, I continued walking along the aisle with my three pesos in hand until I met up with Liz and Charlotte and began talking to a charismatic shop owner, Luis. He talked to us about Cuban-U.S. relations, the need to take communal responsibility for each other and work towards international solidarity. He discussed the embargo against Cuba, stating that while it is an economic policy, for him and for Cubans it means death and starvation. Luis had gone to school for engineering and also served time in the military, however he said he enjoyed working at the market and meeting people from other countries. Luis was like the many passionate, kind, and intelligent Cubans we met, willing to discuss difficult and controversial topics with us and embraced the exchange of ideas. I spent my last few cucs on a small wooden flower he had for sale on his shelf.

After being out to explore for a while, we returned to Centro Pablo. We visited the center to deepen the relationship between Cubans and Americans and to continue the cultural exchange between us. The prominent event of the day was the photo exhibition titled: Mata Ortiz: vida cotidiana – by Dickinson College photographer Carl Sander Socolow, graduate of Dickinson College class of 1977. His photo exhibition focus is on the transformation that is occurring in the remote town of Mata Ortiz in Northern Mexico, through the growing tourism in the area due to the exquisite ceramic craft that is growing there.

The show was a great success, attracting many Cuban citizens into the center. Carl received many compliments on his work and exchanged contact info for further dialogue with Cuban photographers.

After Carl’s opening, as is customary at the Centro for openings, there was a celebration in the courtyard and a concert was put on by some of the trovadores. We had the great fortune of listening to Raúl Marchena and Diego Gutiérrez before leaving Centro Pablo. I recognized Raúl from earlier in the day at Centro Pablo; he had been operating one of the cameras filming the events. This was part of Centro Pablo’s multidisciplinary approach, encouraging artists to venture into and improve their skills in a variety of mediums. -Charlotte, Eddie, and Daniela

Day 7: Friday, March 16

A very exhausted group, we had a small window to sleep in, which was partially interrupted by the sounds of roosters and children next door to us. We ate our usual breakfast and left to attend a lecture on US-Cuba relations at FLACSO in Havana. The lecture, given by a young University of Havana professor and foreign relations expert, provided a comprehensive overview of the history between the two countries. He reviewed, in detail, the multiple governmental acts that constitute the current embargo-blockade on Cuba. Using this as context, he then focused on the recent developments with the election of Barack Obama and where the Cuba-US relationship might be headed next. He explained that many Cubans expected Obama to be able to break at least sections of the embargo down but realize that he has received significant resistance by governmental bodies. In terms of the future, he emphasized the recent oil finds on the northern shores of the island and the upcoming elections in 2012 as the two factors that may change the way Cuba and the United States interact.

After an interesting lecture, we returned to the center for lunch and to pack our bags for our trip to Varadero, a famous beach area east of Havana. However, we first made a stop at a local elementary school, Escuela Primaria Fabricio Ojeda.

Our visit to the Fabricio Ojeda Elementary School was much anticipated. We took some gifts of notebooks, coloring notepads, crayons, and markers for the children to enjoy. We had learned a bit about the Cuban educational system through our class and our interactions earlier that week with Cuban students from the University of Havana. When we arrived the friendly faces of the principal and some administrators greeted us. They first showed us the office where they worked and explained to us that every year of schooling had a different theme, whether it was an anniversary of the Revolution or the celebration of a certain event.

We noticed a bust of José Marti in addition to portraits of Ché and Fidel Castro. As we walked around, we could see some students wearing costumes waiting downstairs for what we would later find out was a performance. We walked up to the classroom and saw the children. They were all dressed in a uniform of a white t-shirt and maroon jumper. The children had scarves around their necks. These scarves denoted them as belonging to a certain year of schooling but they are also worn because the students are known as “pioneers.”

The children we visited wore blue scarves. We got to visit with the first grade children and sang “Itsy Bitsy Spider” and asked them a bit about their schooling. When asked about their favorite subject, most of the children said mathematics. We were then told the ways in which plants grow and given some revolutionary words about the Cuban Revolution. One child went so far as to explain the symbolism behind the colors of the Cuban flag. These kids were incredibly bright for six year olds! It seemed like the dedication of the teachers had a lot to do with the success of the children. The teachers we talked to had been working at the school for over 20 years.

After visiting a few classrooms, we were then treated to the performance of a choreographed salsa number by the students and a few songs. They performed well and had some great moves!

At the end of the performance we were all given doves that bore urgent pleases to help the Cuban Five. The Cuban Five is a group of Cuban men who travelled to the US to thwart anti-Cuban terrorism from the US and were subsequently jailed. These men have gained such symbolic importance in Cuba in terms of US-Cuban relations. We thanked our hosts and then we had a few minutes to enjoy some sugar cane juice from a stand right outside the school. In addition we were able to take a few minutes to look around a local bookstore and finally have an opportunity to spend some of our Cuban Pesos. Back on the bus, we settled in for a two hour drive to Varadero Beach.

Following our tour of the school, we left for beach and our first opportunity to take in the Cuban landscape in its most beautiful form. The drive to Varadero contained some of the most beautiful views that most of us had ever seen. The breath-taking views of the coastline on one side of the bus contrasting with the vast forests on the other were truly an experience.

Although we arrived at the beach and our temporary home for the evening (the Center for Social and Educational Services) at night, it was obvious that the area was pristine and would not disappoint. We had a delicious dinner and set out to experience this new area of Cuba. We found a small outdoor store and decided to all relax by the oceanfront and take in the scenes of nightlife from a different perspective. After a short visit to the beach under the moonlight and dancing at Calle 62, we decided to return to bed and looked forward to the beach.- Jordan, Joe and Marilyn

Day 8: Saturday, March 17

CESERSE and Varadero Beach

By Saturday, everyone was excited to kick back and relax at Varadero Beach, a famous tourist spot known for its white sand beaches. During our time in Varadero, we stayed at CESERSE, the Center of Social and Educational Services. CESERSE is run by Varadero’s Reformed Presbyterian Church and the leaders of the Christian Conference for Peace. The Center’s primary objective is to provide spaces of education, culture, and healthy recreation that address the needs of a highly vulnerable segment of the population, namely senior citizens and groups of children suffering from both acute and chronic medical conditions. CESERSE also provides lodging for outside groups, especially those visitors looking to experience daily life in Cuba. This is the context under which the Dickinson delegation was provided lodging at CESERSE.

On Saturday morning, we slept in and enjoyed another delicious meal at CESERSE, this time with a full view of the beach. After a serious round of sunscreen applications, we headed to the ocean to enjoy the beautiful Caribbean sun. While some chose to indulge in a beachside massage for only 10 CUC, others just enjoyed the sun or swam in the supremely clear, turqouise water. Before heading back to Havana, many wandered through the tourist shops and bought souvenirs. Then we boarded the bus for an evening drive back to the capital city, stopping to enjoy a beautiful view at one overlook spot and enjoying the scenery out the bus windows the whole way back.

An exhausted crew rallied for one last night out in Havana that evening, heading out to a discotech where Alberto’s daughter was performing. The discotech was quite unlike anywhere else we’d been in Cuba; they played music from the 70’s and 80’s in the US, complete with black lights, a disco ball, a big screen TV playing music videos, and dancers leading clubgoers in a rendition of the Electric Slide. As we listened to selections by Michael Jackson, Kool and the Gang, and the Beatles, Alberto explained that music from that time period in the US was considered very subversive in Cuba during the era of strong Soviet influence. Now, in the wake of the Special Period, 80’s music is symbolic of a new space for cultural freedom. When Professor Past asked Alberto if he listened to it, he smiled slyly and said yes. We, on the other hand, did not need to be convinced that the music was cool- Dickinson students and professors alike were spotted tearing up the dance floor one last time, joined by a visiting delegation of students from Connecticut College. After an exciting final night in Havana, everyone returned home to pack and prepare for the long trip home. – Rachel

As we turned onto another road away from the dog, I remember feeling uneasy and wished Don Quixote would have stayed with us. Moments later, he came around the corner through the alley, tail wagging with his head held high. He came right to me and walked us the rest of the way back to the Center. I stayed behind the others on the porch for a few minutes and thanked him. The next morning when we headed for the airport, little Don Quixote was waiting for us on the sidewalk. Excitedly, I gave him a big hug and thanked him again, and got on the bus. As the bus pulled away, he began to bark. As we turned the corner, I realized that he was following us. He was running as fast as he was able to stay with the bus and he had no intention of letting us leave. He followed us for several blocks until he ran out in the middle of the street and sat barking at the front of the bus, unwilling to move. At this, we decided to bring him onto the bus, and take him to the airport with us. During the bus ride, the little man sat between my legs licking my face and chewing gently on my nose. This may sound silly to some, but I think this dog was a guardian angel of some sorts. – Liz