Alyssa DeBlasio, Dickinson College

The first edition of the classic Soviet cookbook, The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food (Kniga o vkusnoi i zdorovoi pishche) was published in 1939. This was the opening season of the All-Union Agricultural exhibition, which welcomed tens of thousands of visitors each day from August through October of that year to gawk, sniff, and poke at the culinary mirage of Soviet farming. Stalin had just signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany. “Life is getting better, comrades. Life is getting happier,” he proclaimed at a conference of Stakhanovite workers in 1935. By 1936, this infamous quotation was immortalized in a march by lyricist Vasilii Lebedev-Kumach and composer Alexander Alexandrov, the former having written the music for the national anthem of the USSR (which, incidentally, was readopted in 2000 with Vladimir Putin’s rise to office). By the end of the 1930s, every school child knew “Life is Getting Better” by heart, and Stalin’s declaration had become the motto of high Stalinism and the pre-war period.

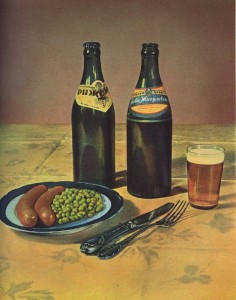

If we judged the quality of the Soviet standard of living by the illustrations in Tasty and Healthy, life was getting better. On the inside back cover, a table set with rose china and crystal champagne flutes is crowded with wines, liqueurs, chocolates, pastries, and fresh flowers. A bottle of Soviet-made Sovetskoe champagne, first produced in 1937 on the direct orders of Stalin to the Politburo, chills on ice in the center of the table. The book is so canonical that it has inspired several literary attempts to “cook one’s way through it,” most notably Anya von Bremzen’s Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking (2014).[1] Nowhere does the advice contained inside the embossed Stalinist tome betray that 1939 was also the height of the purges, where in a few years time around a million people were executed or died in detention. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition closed its doors.

Tasty and Healthy was not just another instance of lakirovka, or the “varnishing” of reality with sugar-coated (literally) representations of the Soviet farm and table. It was first and foremost a manual for daily life. Written under the auspices of the People’s Commission for the Food Industry of the USSR, it also included information about nutrition, harvesting, cuts of meat, and table manners. In a cookbook for an ostensibly classless society, in whose mythology even cooks could rise to the top of the Soviet ranks, class aspirations and realities were visualized on every page. Alongside images of culinary luxury were modest concoctions, such as Siberian pel‘meni and buckwheat porridge with butter. Soviet citizens were instructed how to cook what they could afford, and then enlightened on what they would afford … one day. Life was getting better, after all. Tasty and Healthy was a versatile manual for the average Soviet citizen—a cookbook for day-to-day preparation as well as a culinary projection into the utopian future of the Soviet project, falling firmly within the broader edification campaign of high Stalinism that aimed at instilling in every Soviet citizen a mind towards kul‘turnost‘ (culturedness).

Today, in the midst of a currency crisis that has earned the Russian ruble the status of the worst performing currency of 2015, life may not be getting better or happier, but it is certainly getting tastier. Or, at least, that’s according to a new ad campaign at the Shokoladnitsa chain of coffee shops, which picks up on the Stalinist motto in its new slogan: “Life is getting tastier.” Coffee shops like Shokoladnitsa are the symbol of the elusive Russian middle class. This particular brand, which takes its name from the word for “chocolate,” was founded during the end of the Thaw but began to expand and operate “according to European standards” (in the words of their website) only in 2000.[2] This was the year of Putin’s inauguration as President of the Russian Federation, when the “strong hand” from Russia’s northern capital ushered in a period of perceived financial and political stability. Suddenly life seemed better and happier not just for Yeltsin’s “new Russians,” who earned their money in the privatization of the early 1990s, but for the average Russian. And their tastes, like their class means, were average. Coffee chains sprung up in major cities, shopping malls were populated by foreign brands, and advertisements for cookie-cutter suburban cottages promised to whisk city dwellers away from the prying eyes of urban life. In cafes like Shokoladnitsa, patrons with middle class aspirations could eat overpriced sweets and be seen spending money, the logoed bags from their shopping conquests strategically displayed at their feet.

Now these cafes are emptier than before. Inflation on food prices has surpassed 15% and the exchange rate, displayed on every corner, changes daily if not hourly. The newest additions to Shokoladnitsa’s 2015 menu are a return to traditional Russian meals, dishes that straddle the border between peasant minimalism and those ubiquitous French-inspired recipes eaten at every birthday celebration and on every holiday. For 300 rubles ($4.80), plain chicken broth is served with a thin slice of mushroom and chicken tart; for a quarter more, a spoonful of beef stroganoff is ladled over a mound of powdered mashed potatoes. These are the meals of a true middle class, one that subsists on a healthy capitalist diet of moderation, fear, and fantasy. If “life is getting tastier,” it is only in the middle-class imagination. The images on the advertisements depict the new realities of Russia’s financial diet: a single milkshake, one slice of cake, or a thin pair of rolled Russian crepes. As patrons trickle in to beat the cold, the advertisements are a reminder that even when times are tough—especially when times are tough—there is always value in fantasy. As the cards placed on each table reassure, “The exchange rate of chocolate is always stable.”

February 2015

[1] Anya von Bremzen, Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking: A Memoir of Food and Longing (NYC: Crown, 2013). See also: Maryam Omidi, “Soviet Kitchen: A Culinary Tour of Stalin’s Iconic Cookbook,” The Calvert Journal (November 11, 2013), (http://calvertjournal.com/articles/show/1746/soviet-kitchen-culinary-tour-of-stalins-iconic-cookbook. Last Accessed February 26, 2014.

[2] “O kompanii,” Shokoladnitsa, http://www.shoko.ru/moskva/o_kompanii/. Last Accessed February 26, 2015.