Theodora Trimble, University of Pittsburgh

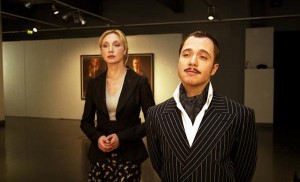

The Liubov’-Morkov’ trilogy adapts the popular Freaky Friday trope of American cinema to explore family values of the post-Soviet middle class. The first film begins seven years into Marina and Andrei’s marriage when the couple visits a psychologist in order to address their relationship troubles. They wake up to find their bodies swapped: Marina must go to work as a lawyer and Andrei as an art critic. The magic is reversed after they team up to defeat a group of museum crooks and achieve a greater mutual understanding. The role reversal in the second film occurs after Marina and Andrei have children. Their twins must go to work, navigating their parents’ high-power jobs, and the adults are forced to attend school. The third film follows the couple as they wake up in the bodies of their own parents, Andrei as his ex-army colonel father and Marina as her geriatric mother.

The films engage with family values in contemporary Russia through their quest to normalize the nuclear family while also foregrounding Marina and Andrei’s financial status in the efforts to reverse the body swaps. The story continues a long tradition from Soviet cinema that considers the reconstitution of the nuclear family as its central concern. During the years of the Thaw, for example, Soviet films explored this problem through melodramas that took the death of Stalin and mass casualties from the Great Patriotic War as points of departure for rebuilding broken generational relationships.

In the second and third installments to Liubov’-Morkov’, familial dysfunction shifts from the center of marital discord to the locus of generational divisions. Marina and Andrei, as well as their parents, however, notably have socialist amnesia, eliminating memories of Soviet culture as the cause for familial ruptures. Their affluence becomes both the problem and guiding force to their understanding of values, as the rebuilding of their family is achieved through Western, capitalist socio-political standards.

Writing about the nuclear family in the American context, Rayna Rapp argues that the family reflects and distorts material relations as a “socially necessary illusion which simultaneously expresses and masks recruitment to relations of production, reproduction and consumption—relations that condition different kinds of household resource bases in different class sectors” (181). Without conflating post-Soviet family standards to those of an American middle class, it is worth noting that the Liubov’-Morkov’ films connect the value of a heteronormative nuclear family—or the illusion of one—to a particular class status. The second film, for example, moves Marina and Andrei’s living space out of a city apartment and into a suburban mansion.

The films also suggest that the family in contemporary Russia is linked to state campaigns. The third film follows Marina and Andrei as they defeat a group of villains who are trying to rob Russia of its Fabergé egg national treasures. Saving the family becomes synonymous with saving the state: once the threat to Russia is absolved, the family may also thrive and grow.

The years of Vladimir Putin’s presidency have been marked by a series of state campaigns that concentrate on the building and preservation of the nuclear family. In search for a solution to combat the country’s demographic woes, the state was responsible for spearheading a new incentive program across Russia in 2007 to combat its depleting birth rate. The Russian Day of Conception, 12 September, is a national day of procreation, as couples who successfully give birth on 12 June, National Day in Russia, are eligible to receive cash incentives for having children.

The increasing number of policies directed at homosexuality and homophobic propaganda in recent years adds to efforts to mold Russian family values according to state standards. If one considers the Reagan era in America as representative of a moment in which the conflation of conservative religious principles merged with politics to advocate family values—and pride in having capital—as the core of moral standards, Russian state efforts have also succeeded in making politics the center of the post-Soviet middle class family. Recent Russian cinema also considers evolving state principles with respect to the representation of the family on screen, ensuring that Putin’s politics will continue to merge family values with those of the so-called middle class.

February, 2015

Works Cited:

Rapp, Rayna. “Family and Class in Contemporary America: Notes Toward an Understanding of

“Ideology.” American Families. Ed. Stephanie Coontz, Maya Parson, and Gabrielle Raley. New York: Routledge, 1999. 180-196.