Intermestics and the SDGs

April 18, 2024

Prompt: How does the interaction of international and domestic factors empower or hinder some states of the Global South in making progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals compared to other states?”

There are multiple ways that international domestic factors affect state success in achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. However what helps or hinders a country’s success is highly dependent on regional or even country specific factors. Consider one factor that relates to both domestic and international perspectives: natural resources, and the case of Kuwait.

The podcast on Kuwait analyzed the country’s progress towards achieving the SDGs in the context of the water scarcity that exists within the region. Water is crucial to development, however in Kuwait like the rest of the MENA, freshwater scarcity complicates the process of achieving SDGs. Water, and similar resources are unique in discussions of development because they are used in so many parts of life such as industry, food growth, or health. The creators of the podcast look at the issues of water scarcity from a sub-regional perspective, analyzing how the GCC states use more water than other regional states. As a listener, this is when I began to consider the effect of other natural resources in Kuwait’s efforts to achieve the goal, and I considered the use of oil rents to fund desalination plants. Indeed, it seems that in this scenario, natural resources are both hindering and helping Kuwait in achieving the SDGs.

As I continued to listen to the podcast, I learned more about an issue that affects other states regionally. Specifically, I learned about how Kuwait relies on oil, and oil income in order to provide water for its citizens. In addition, I learned about the GCC’s efforts to create a regional water grid. I think this is a particularly good example of ways in which regionally, countries might work together to help achieve goals. This seems especially relevant to natural resources and water in particular because there are likely shared groundwater reserves or rivers that impact the way states consider water usage internationally. I’m inclined to believe that while the problem seems to be domestic or regional, intergovernmental organizations and regional cooperation might be part of the solution. However some might argue that intergovernmental organizations, and increased cooperation and interdependence are not how states are inclined to act. Do you think there is potential success in a regional water grid? What might some challenges be to implementing a successful water grid?

https://softwater-kw.com/en/water-desalination-plant-in-kuwait-2/

Consider now the case of natural resources in Iraq. The podcast on Iraq considered the way natural resources, in this case oil, drives inequality and hinders the country’s ability to achieve SDG 10. I wonder if one could consider inequalities caused by oil to be a domestic issue or an international issue or both? I ask this because I wonder if the cost of oil and associated wealth might be in part due to organizations like OPEC and countries that purchase such oil, or internal usage of those funds. Is the problem one of oil rents itself? Or is it a problem of a “culture of corruption”? I think the issue of usage of oil rents and inequality is an issue prominent in the region, however the issue seems to play out in different ways depending on the state and regime goals.

Looking towards the future, international factors such as increasing desire for clean renewable energy might decrease reliance on hydrocarbons. This would affect both Iraq and Kuwait considerably and hydrocarbons both help and hinder the states ability to achieve the SDGs in differing ways.

When I compare both the states to Morocco, I think about the importance of international non-governmental organizations like Transparency International in collecting and spreading data on country progress. It has for me offered a unique way to compare the country’s success and failure in things like corruption. However, as we mentioned, and another student in our zoom mentioned, sometimes international standards and metrics are not robust enough to enact any real change. What do you think?

My Water Diary

April 1, 2024

It seems important to note first, that while my water usage is lower than the average American’s (1,013 g/d to 1,802 g/d), a lot of this I attribute to Dickinson college making such lower water usage accessible (https://www.watercalculator.org/). For example, my shower at Dickinson has efficient faucets, but the house I grew up in does not. Additionally, Dickinson makes sustainability, like recycling and getting used clothing very easy. Therefore, one must take into consideration the ways the lifestyle of a Dickinson college student differs from the lifestyle of the average American.

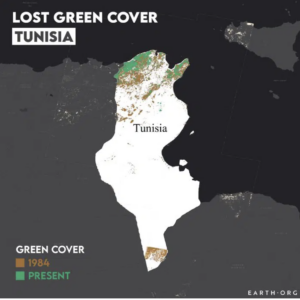

The average American water footprint is 7,800 litre/day or 2060.542 gallons/day. My sub-region of study is North Africa so I looked up Tunisia to compare. The average Tunisian uses 6 100 litre/day or 1,611.44 (gallons/day.https://www.waterfootprint.org/resources/interactive-tools/personal-water-footprint-calculator/). Socially, I think it is likely Tunisians consider water scarcityin their activities and everyday lives, in a way that people in the US don’t.

https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/2022/12/21/tunisia-raises-price-of-drinking-water-by-up-to-23-per-cent/

Economically, water scarcity is going to make water demanding goods expensive, and is going to limit who is able to access goods. For example, foods that require a lot of water to grow are going to be expensive and inaccessible locally, and might be cheaper to import. Countries without oil wealth, like North African countries, might find such imports out of reach. Perhaps it would also mean it will take more water to consume things.

This means that Tunisia has to import virtual water from countries, likely from outside the region given how scarce the surrounding region is as well. Internationally, Tunisia must maintain good trading relations with the countries they get this water from. Water scarcity also means the Tunisian government must have the funds to import virtual water. These patterns present challenges to sustainable development.

I am writing my final research paper on food security in Tunisia, and part of the problem is the arid climate makes sustainable food security difficult. Reliance on imported food, which is virtual water, makes the country vulnerable, presenting foundational challenges to human life. Patterns of reliance on external countries for virtual water pose challenges for countries because it makes them vulnerable to price shocks, issues with transportation, etc. Are there any other ways you can think of water scarcity posing challenges for MENA countries? Did you notice different challenges for different sub-regions?

Learning to Read

February 20, 2024

Adam Kostko, a humanities professor at a liberal arts college, argues in his article “The Loss of Things I Took for Granted,” what he considers to be a crisis of literacy amongst today’s college students. Kostko is careful to describe the crisis as not the fault of students but distributors of literacy education.

Specifically Kotsko calls attention to students’ alleged inability to gain meaning from readings and even understand the words within reading themselves. Recalling anecdotes from the classroom, Kostko explains that students find even short readings to be “intimidating.” So too, according to Kostko, students struggle to read at all, let alone read and understand.

As a current student, who reads what I would consider to be 20-60 pages on average for each class, I appreciate that Kotsko understands the importance of reading prior to class, and its significance to college students’ education. However, I disagree with Kotsko on a few points.

Firstly, I disagree that students find ten pages or more to be intimidating. Certainly, I’ve heard students complain about reading loads but I have yet to meet a student who does not believe in their ability to read or read well. Second, I find that Kotsko’s definition of meaning in reading is somewhat narrow. What is considered meaning in the humanities, is different in languages, or STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). To fail to address such differences means that the reality of student experiences might have been overlooked.

Kotsko lists the common explanations for the alleged decrease in literacy. The first of such is the argument that technology, specifically smartphones, are too distracting for any person to read for an extended period of time, thereby corrupting the reading experience. Kotsko does not seem to consider this to be the main contributor for the problem, but they do not discredit this explanation entirely.

I do think technology has changed the way students read, however I do not think it is an exclusively negative change. I argue that the way we communicate has changed because of technology. Because there is so much content online, I typically rely on clear and concise information in order to understand what is happening regarding a certain topic. Writings that do not quickly or clearly explain meaning or purpose can be tedious and time consuming. Current college students might be expecting different types of communication from students in the past. So too, on days I find my phone to be particularly distracting, I power it off until I finish my readings in order to focus. I know at least some of my peers do the same.

Kotsko acknowledges that the pandemic, and possible gaps in education may contribute to students’ inability to read as well as they did in the past. However, Kotsko again argues that the true cause of students’ declining literacy is elsewhere.

So why might today’s college students be struggling to read? According to Kotsko, its academic policies like No Child Left Behind emphasize students’ ability to test instead of their ability to read and understand written information. Educators have jeopardized students’ abilities, in favor of higher test scores that would bring about better funding.

The problem is so extensive that according to the author, students’ literacy or their ability to read at all, let alone read well, has been ruined, because reading long texts doesn’t help students achieve higher test scores. I disagree with this argument most. Kotsko argues students are unable to find meaning in readings, and read for extended periods of time; however, tests and school require students to focus for extended periods of time. Is it impossible that other types of focus can translate to focus in reading? In addition, I do not think that preparing students for tests is what has jeopardized their education.

For example, Kotsko gives an example of a student who is unfamiliar with basic vocabulary and criticizes common core standards for failing in students’ phonics education that would help them understand. I do not think vocabulary issues are just issues of instruction, but also lack of reading variety. I read Lord of the Flies four times during my middle and high school years. In addition, I read The Crucible, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Odyssey at least twice. The lack of communication of works taught in a small town, in schools is astonishing. At the time, I was appreciative of the fact that I didn’t need to reread the novels as carefully, but looking back, I think it would have been good for me to read different authors, in different styles. This isn’t to say that such classics don’t belong in high school classrooms. I’m simply arguing that a specific set of classics is taught, but often students get little other literary exposure that not only could have bolstered their education, but also have made them interested in reading itself. Indeed, most of my vocabulary comes from reading science fiction and fantasy novels during free periods in high school. If we are to focus on failures within the humanities, I would consider this to be a major one. In highschool I was never taught to appreciate alternative written works such as journalism, academic reports, etc. All of these styles, though, I interact with regularly in my classes. Indeed, it was a sharp learning curve during my freshman year of college trying to understand writings that were not in the form of a novel.

Therefore I appreciate Kotsko’s concern, however I think he missatributes the sources of such problems. In addition, the problem Kotsko describes seems somewhat overstated, and is framed in a highly contextual way. Indeed, how I do my readings for class is dependent on how I will be interacting with the text in class and in my assignments. Meaning each time I read, I apply different techniques.

Here is the article if you are interested in reading: https://slate.com/human-interest/2024/02/literacy-crisis-reading-comprehension-college.html

If you disagree with my critiques, or have an experience that differs from mine feel free to share. I am a student, not an educator, so I do not doubt that there are factors to this argument that I am missing.

Othering

February 18, 2024

Prompt: Taking the concepts of self and other, think about your community (your home, your college or university, some other community in which you are involved) and consider who belongs and who is an outsider.

This prompt reminds me of a conversation I had with a student who had grown up in Carlisle, and prior to their time at Dickinson College considered the students to be outsiders who came and went, but were relatively disconnected with the community. In my current community at Dickinson college, I consider similarly situated individuals to be a part of my community. This generally means I perceive students to be my community, and those who inhabit Carlisle to be “others.” This conversation made me question what specifically makes me consider someone a part of my community.

To me, those who share experiences with me, such as studying, finals, school dances, and student jobs are similarly situated, and therefore are a part of my community. They likely share my needs, desires and frustrations.

Those who I experience as a distinct individual are usually people I interact with. Even if such persons are acquaintances, I consider them to be individuals, with specific interests, and habits. Plural others are more likely to be people I know of but don’t interact with, such as those on the Dickinson sports teams. Based on an interactive approach, I don’t usually form perceptions about people I know as plural others. However narratives about plural others, without any other contextual or historical information, can be influential, in possibly dangerous ways. So for example, if one hears a rumor about a specific team, and they have no contextual knowledge to explain or refute the rumor, inaccurate or incomplete perceptions can be formed.

Narratives can be tools used to create inaccurate perceptions by those who have no interaction or knowledge to rely on to counter such narrative. In this sense, from an international politics perspective, “othering” can be harmful. If a politician, state or the media, tells citizens a specific narrative to justify their actions, then it can perpetuate such narrative. It also can serve as an explanation for harmful behavior when applied to public opinion. States can also bolster nationalism on a large scale, and perpetuate a narrative of a greater state or national community in order to explain harm or othering. However, that is not to say that nationalism as a source of community or pride is necessarily bad in policy, it is just that it, like many other things, can be twisted to perpetuate harms.

http://www.collegecompare.com/dickinson-college

In another sense, othering compromises the ability of people to be understood as multifaceted communities or individuals. Simple narratives or othering can be reductive to the reality of people or individuals. In this sense, othering is tempting as a descriptor of a group because it is easy to accept and move on. To have better understanding means to address personal bias, learn about others, and possibly make your own community uncomfortable by confronting their understanding of people. This dynamic of reducing individuals to the narratives that accurately or inaccurately describe them likely shows up in international politics, in the news media and in policy choices regarding regions. However, because of the failure to take communities and persons for face value, there is risk of inaccurate policy that perpetuates harmful narratives. It is, of course, impossible to completely understand each person or community in their whole, but it is important to let people dictate their own self narratives, instead of narratives created by “others.” We can interact with group we consider to be “others” by listening, and understanding.

TURNING TOUGH CHOICES INTO SCHOLAR-LED TRANSFORMATION-Reflection

February 7, 2024

Dr. Najat Aoun Saliba’s talk on her research and activism gave me insight into the challenges and techniques of change.

Saliba began her talk by summarizing her academic research on air pollution in Beirut and the dangers of smoking different types of nicotine. She explained the methodology behind the projects and why she and her team at the American University of Beirut received international recognition for their findings.

Dr. Najat Aoun Saliba ran for parliament to change smoking, inhalant safety, and air pollution policy. She wanted to apply her research findings to Lebanese society. However, corruption and stagnation within the parliament have hampered her attempts.

Saliba created a system of local solutions instead to combat environmental decline and address humanitarian needs. She considers herself an activist and scholar whose work is based on social justice. One such example of scholarly activism is the international response by scholars to the outbreak of COVID-19 and the search for a cure.

Dr. Saliba described what she considers to be three pillars or steps to sustainable social change. The first is community and contextual research that can be applied to bring about change and given recognition by widespread communities. The second is community-driven solutions. For the solutions to be sustainable, they must work well within communities. The third pillar, which, according to Saliba, has yet to be achieved, is an international change that would bring about social and environmental change in a way that creates accountability. Saliba described that the source of many of the social and ecological problems she has faced is greed and corruption by political officials in Lebanon. Corruption permeates the governing system, making any change that would be costly and difficult to bring about.

Her organization, called the Environment Academy, seeks to bring about sustainable change, such as stopping illegal tree cutting or overgrazing of forests. Her methods include empowering local government authorities to participate and co-create change with the organization.

Dr. Najat Saliba https://www.aub.edu.lb/articles/Pages/Najat-Saliba-For-Women-in-Science.aspx

According to Saliba, success is dependent on the analysis of the problem in the context of individual towns and communities. To bring about such change, the organization must connect scholars, lawyers, government authorities, and the communities. With such strong support in different areas, fighting against corruption can be more synchronized. Patience and small steps towards big change are considered to be pillars of change as well.

The talk “Turning Tough Choices into Scholar-Led Transformation” made me think about how this method of scholar and community led transformation can be applied to Carlisle. First students and educators should identify issues within the area that we think can be addressed through policy and community engagement. It seems to me, that the most important factor for change, atleast for Saliba is cooperation and participation from people from different disciplines and domains.

Where I Live: Where They Live

February 2, 2024

First and foremost, it seems crucial to mention that often the places we live, and the places we call home are different. This factor came up frequently in the two discussions this Tuesday with the AUS students. Students often placed markers in places where their family lives, or where their family is from instead of the places they currently dwell. A common theme throughout such discussions was family and community. Often people selected the places they did specifically because they identify closely with communities there. Though we did not discuss culture a lot, people were able to talk about societal customs such as talking politics at family gatherings. I found this particularly interesting, as my family makes a point to avoid talking politics at family gatherings. In addition, we found that shared objects brought questions about cultural differences such as discussions regarding uses of incense.

Environment seems particularly relevant to our conversations, though it was never directly addressed. Often students mentioned outdoor recreation as a common extracurricular activity. It seems to me that outdoor recreation looks different around the world. For example, in the Winter I enjoy the snowy weather. However, some students may not live in areas with snow. Likely outdoor recreation may look entirely different. In addition, one student and I discussed agriculture. Specifically through olive trees. They mentioned that they have a family member in Jordan who grows olive trees, which reminded me of my grandmother who lives on an olive grove in California. I Imagine growing olive trees might be different in each area of the world based upon climate.

Through our shared objects, I discovered a few universal values. One of which is family. Often the objects were those that were gifted by relatives, or those that reminded us of relatives or friends. We were also able to talk about what se

emed to be universal desires, such as a commonly held desire for better food options on or near our campuses.

Particulars, such as love of reading, sports, or travel also became apparent through students sharing personal objects. When showing objects that are important to them, students demonstrated their values. It seems there was not a single student that chose an object for an entirely superficial or meaningless reason. For example, I didn’t pick the necklace I showed to my peers because I think it is pretty. Instead I chose it because it was gifted to me by my grandmother, and therefore holds familial and sentimental meaning.

- The necklace I brought in as my object.

Other objects, such as an alarm clock, appealed to shared experiences, such as the need to arrive in class on time. Regardless of what the object was, it seems there were many ways that we were able to connect to each other through our values, needs, and desires. I am glad I was able to connect so well with the other students.

If I did not get a chance to talk with you in our groups, feel free to comment what you brought in as your object! Do you think it demonstrates a particular or universal value? If the object has familial or cultural value, please feel free to share about the object and what it means to you!

Tools of Authoritarianism and Change in MENA

December 12, 2023

To me, when studying authoritarianism in MENA, tools that have broad analyses or specific analyses are valuable, just in different ways and at different stages in the learning process. One crucial tool for studying authoritarianism in MENA is structural analysis of the numerous factors that affect authoritarian regimes’ outcomes. A Political Economy of the Middle East offers such broad analysis. This source uses categories to understand the larger internal structures within regimes. Broad categories helped me compare and contrast large regional differences so I could better understand individual cases. The author’s methodology helped me see what factors existed across regime types, and I was able to identify those as important. For example, I understand now that rapid growth in population leading to less job availability is a problem that affects multiple countries. By using population statistics, I was able to draw conclusions about the causation of events such as the Arab Spring. Therefore, I think the model of A Political Economy of The Middle East is valuable because it demonstrates the importance of economics and demographics in authoritarian regimes beyond the actions or policies of a regime itself. This tool of the region spanning approach is especially useful when learning about vocabulary for studying. However, the additional context of things such as colonial history or former leadership was a bit brief, but I do think they are essential to look at.

Detailed cases such as Wedeen’s book on Syria, especially after reading about regional trends helped me better understand how differences such as population, sectarianism, regime, leadership, military, etc. change outcomes. In the case of Syria, an in-depth look was essential to my understanding of how the Arab Spring has escalated into a Civil War. Indeed, some outcomes cannot be accurately understood by applying the same concepts to every country. Such an issue seems similar to Lisa Anderson’s argument in “Searching Where the Light Shines: Studying Democratization in the Middle East.” One of the issues we discussed was that scholars frequently use language and concepts occurring in other regions to explain what is happening in MENA, discounting the complex history of the region. So too, it seems that this could apply to individual countries in MENA. For example, the dynamics that exist between rulers and citizens in Saudi Arabia are likely going to vary in many ways with the dynamics in Egypt or Tunisia. So while categories are excellent for understanding general trends, Weeden’s individual focus is valuable for in-depth understanding.

In addition, Wedeen seems to frame the book from the perspective of a citizen who has internal responses to things such as propaganda, and protest. Wedeen’s focus helps readers understand what’s happening within a country and also was is happening to citizens and communities. Such an analysis seems similar to our time spent talking about Tunisia, and analyzing different regions in the country and economic factors that drive dissent. Individual studies allow for analysis of colonial histories or the specific effects of natural resource wealth.

By studying particular actors, especially those in power, I understood why some regions had differing economic outcomes or were in different stages of democratization. Leadership is important in authoritarian regimes, but using categories may not always describe all the effects.

In addition, there seems to be different rhetorical value in each work. Wedeen writes from the perspective of Syrian citizens and in an arguably less analytical way than the authors of A Political Economy of the Middle East. As a reader, this meant that the writing was not only more approachable, but I was also able to appreciate the impact of the authoritarian regimes on citizens. However, A Political Economy of the Middle East offered graphs and statistics to show trends and back up claims.

Overall, I think each type of perspective and type of methodology can be a useful tool, depending on levels of understanding of the topic. But if real understanding is the goal, you cannot utilize just one type of tool.

References:

Cammett, Melani Claire, Ishac Diwan, Alan Richards, and John Waterbury. A political economy of the Middle East. Routledge, 2019.

Monarchies and Political Unrest in the MENA

November 2, 2023

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/king-declares-morocco-a-constitutional-monarchy/

Authoritarian leaders are likely never in a position to rest easy. The complex requirements of maintaining trust and bribing elites, combined with the need for suppression and acquiescence, means that maintaining authoritarian rule is a difficult task. Since the Arab Spring and the last decade, social and technological factors have given monarchical authoritarian leaders even more reason to worry.

In my view, the most critical factors that have challenged or continue to challenge authoritarian rule are broad regime civil or social traits that translate to challenges and create political unrest, such as the Arab Spring. The main challenges I see facing authoritarian monarchies in the MENA are 1) problems associated with a surplus of educated, unemployed youth and 2) issues within regimes, such as discontent or conflict within royal families that threatens legitimacy.

Using these challenges and examples from MENA monarchies, I will demonstrate the ways such factors threaten regimes as well as the ways monarchies defend themselves. Consider Morocco during the Arab Spring. The protestors were like those in many other MENA countries: young, unemployed persons who were well educated (Khatib and Lust 2014, 324). Young people are given high expectations for job markets and find no work available, leading to unrest. Unlike previous uprisings, the mobilizations during the Arab Spring, not just in Morocco, social media, and the internet allowed movements to reach further. In addition, it is that the protests occurring in other MENA nations displayed on the news inspired protestors, as was discussed in class. The added factor of technology and rapid connection might make authoritarian leaders nervous about their ability to control populations.

However, the protests in Morocco were unsuccessful for numerous reasons. One reason is that the structure of the Moroccan government itself has a long-standing monarchical history. Therefore, there is an added element of legitimacy that might have discouraged populations from desiring to oust the monarch. Instead, they sought government reforms (Khatib and Lust 2014, 224). A country such as Morocco might not have the economic resources to buy off citizens, so given that citizens did not desire a new regime type, the government could appease them with the promise of change or a few minimal changes that took so long to occur that political action had decreased (Khatib and Lust 2014, 228).

Therefore, monarchies may be well suited in some regards to counter protester hostility. Appeals to legitimacy through real or perceived claims of tradition and religion allow leaders to create a certain reverence around themselves. Non-monarchical authoritarian regimes may not have such success in cultivating perceptions of legimitacy.

Consider Bahrain, which faced some of the most political unrest during the Arab Spring. The Al Khalifa ruling family was new compared to other dynasties, and social splits and inconsistencies in Royal power weakened political strength (Khatib and Lust 2014, 173). Consider first the Royal family, internal factions, and bribery that can weaken family power and create public dissatisfaction. For example, many of Crown Prince Salman’s economic reforms financially injured his uncle, who happened to be the prime minister. In addition, Prince Salman used bribery in order to further his economic goals. These reforms led to a split that politically weakened the family and regime (Khatib and Lust 2014, 180-181). Therefore, families are not always ideal for political uniformity, weakening their stance. In the end, Bahraini authorities called on outside security forces in order to suppress the protestors during the Arab Spring, utilizing regional and political connections from exterior states.

Therefore, there are many ways in which monarchical regimes can specifically defend themselves against popular movements that might harm them. Such ways include appealing to legitimacy to protect a real or perceived cultural role, limited or promised political reform, and physical repression, atleast in rentier states like Bahrain. The tools of legitimacy perhaps works both for and against MENA monarchs as many of them were established recently, meaning their claims to power are not embedded in tradition in the ways that Morocco’s might be. So too, many regional monarchs are active in some, but not all political affairs, insulating them from public dissent with political systems. Monarchs can blame other actors for government downfalls(Lucas 2004, 108). In addition, it would seem that regimes can also prevent unrest by limiting repression physically and politically as the Moroccan monarchy did and faced less backlash in 2011 as a result (Khatib and Lust 2014, 228). However, even authoritarian monarchs with extensive repressive capabilities and real legitimacy don’t rest easy, given the success of some countries in ousting monarchies and the changing realm of political participation.

Khatib, Lina, and Ellen Lust. 2014. Taking to the Streets: The Transformation of Arab Activism. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Russell, Lucas. 2004. “Monarchical Authoritarianism: Survival And Political Liberalization In A Middle Eastern Regime Type” International Journal of Middle East Studies 36, 1: 103-119

A Siege of Salt and Sand-Review

October 2, 2023

The film A Siege of Salt and Sea is an informative piece demonstrating how the combination of geographical location and climate change impacts the traditions and livelihood of Tunisian citizens.

https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/lost-green-cover-Tunisia-1.jpg.webpmoney.

By interviewing citizens and scientists instead of politicians or authorities, the filmmakers captured how desertification and rising sea levels impact daily life. The citizens spoke of their worries for the future, their children, and how climate change affects how people live and spend money. Climate change has forced many Tunisians to choose between supporting their families or fighting the impact of climate change. In addition, citizens experience how insect infestations affect daily lives, even when politicians may not be inclined to elaborate on such issues.

Many interviewees spoke of their childhood and the rapid change that has occurred in the last decades in their hometowns and regions.

The film’s structure also demonstrates that much of the pressure to mitigate the effects of climate change is placed upon affected citizens when policy is a preferable way to tackle the issue. Multiple persons mentioned their dissatisfaction with how authorities handled the climate crisis.

The filmmakers also included the Arab Spring and how they have become one of the first nations to include climate change in their constitutions. It demonstrates how the people of Tunisia value the environment and a sustainable future if policy allows them to access such a future.

Rentierism and MENA

September 26, 2023

Michael Ross, in his article, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy, “analyzes rent in the Middle East and North Africa, investigating the negative impacts associated with those who have high national income from rents and connections to authoritarianism. Ross asks insightful questions about how “resource wealth” affects governing bodies and the populations of such states. In addition to his analysis, Ross claims that resource wealth derived from minerals and oil resources makes states less democratic.

https://www.istockphoto.com/photo/oil-refinery-with-twilight-sky-gm505406394-83666411

Given our class discussion and readings, if oil rents produce peculiarly damaging political and social outcomes in the Middle East and North Africa, it is the interaction of rents with other factors, not just the size of the rent itself. Though it may not be immediately apparent what the factors in question are, it is clear that there are other relevant issues than the size of rent alone.

This question reminded me of the video we watched by the Center for Global Development in class and its concept of rent. Consider a country which, due to high rent income, lowers taxes. If the taxes are lowered or nonexistent, citizens may have less power because the rent goes directly to the government and is the government’s money. Such a state that does not utilize its citizens’ money to improve the state is no longer obligated to act on behalf of the population. The state has no accountability. The video addresses this issue by suggesting that rent money goes to citizens. This idea is consistent with Ross’ theory of the rentier effect. States with low accountability must rely on things such as patronage and low taxes in order to maintain control. The relevant chapter from the political economy books suggests patronage will not lead to a sustainable economic future. Patronage also harms those without access to resources like familial connections and, therefore, no clear employment. The video, reading, and Ross’s article suggest that it is not just the size of the rent that matters but also who controls the usage of the rent.

Ross’ article demonstrates that state wealth in relation to its oil rent is a particularly relevant factor to a negative impact on democracy. Ross states, “a given rise in oil exports will do more harm in oil-poor states than in oil-rich ones. Hence, oil inhibits democracy even when exports are relatively small, particularly in poor states.” (Ross, 342). Given that the factor of state wealth compared to oil rent impacts the negative consequences to a country, it seems unlikely that just the enormous size of oil rents makes them damaging. There must be internal factors within countries that increase harmful outcomes.

Therefore, it seems that at least given the resources we have in class, oil wealth and a combination of other factors make states less democratic. However, the issue of the unusual size of oil rents cannot be ignored, and may very well be one of the many factors that create adverse social and political outcomes in MENA.

Center for Global Development . (2012). Oil to Cash: Fighting the Resource Curse through Cash Transfers. YouTube. Retrieved September 26, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8f7MSOLMRk&t=3s.

Ross, Michael Lewin. 2001. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics 53, 3. (Apr.): 325-361