In terms of some background, the block quote I will be analyzing is taken from an interview I conducted for the LGBT Oral History Project, which is not yet published. My interviewee discusses sirb’s (sirb’s pgp) experience in forming the first all black drag king troupe in Central Pennsylvania and how they used to do routines based off of the stepping of historically black fraternities. As sirb says, “We made up our own dance routine, um, our own steps, we might do a few moves of the little stepping, say one of the frats that we saw, mixed with a move from another group back in the day that we seen, just put these all together and come up with our, with what we were gonna do…Yeah, it is, it is, it’s hard to do but, if you look at a lot of steps now, it’s all mixed up. If you just really look at like all the dance steps, you get like you might have Michael Jackson, you might have James Brown, you might have, like just put together. We just added a little bit of this stepping to it without taking the frat’s moves you know we might see something like oh, we like the idea of this hand move motion, we might that. And we might see something else like oh, we like the way they did a dip, so we might go dip. Dip and then do a hand, you know. That’s how we would do it.” It ‘s interesting to think of the implications of a group of presumably gay women, or as my interviewee refers to them, “masculine identified women,” interpreting the gendered behaviors of a group of men. Greek life is seen as one of the most elitist and exclusive institutions in higher education (expressing a generalization and common opinion, not what I think). These organizations often require very rigid expectations in terms of gendered behaviors, such as very strict dress codes, only allowing opposite sex partners for dates, and having parties focused around mingling with organizations of the opposite sex. Due to the historical context of when a lot of greek organizations came into existence (in the South, immediately after the civil war), the dues one must pay, and the climate of a lot of these greek organizations right now (SAE, border control parties, Antebellum South parties), these organizations also explicitly exclude people of color and poor people. As a reaction to the racist, classist, heterosexist, and cissexist implications set forth by these fraternities and sororities, people of color made their own specifically black or multicultural fraternities and sororities. Historically black and multi-cultural fraternities and sororities subvert the elitism of these greek organizations and carve their own stake in a traditional college experience. And while all of these organizations do great work in philanthropy and community organizing, they often continue to perpetuate these strict gendered and sexualized patterns that exclude LGBTQ+ people. Doing a drag interpretation of greek life spins all of these traditions on their head. As Judith Butler says in Gender Trouble, “that the structure of impersonation reveals one of the key fabricating mechanisms through which the social constructions of gender takes place. [She] would suggest as well that drag fully subverts the distinction between inner and outer psychic space and effectively mocks both the expressive model of gender and the notion of a true gender identity” (136-137). As black and multicultural fraternities and sororities complicate the racialized and socio-economic presumptions of greek life while drag performances of their routines subvert their gendered and sexualized standards. This black drag performance accomplishes both of those tasks simultaneously. Drag seeks to complicate cisgender identities, saying that maybe my sex and gender do not always correlate in the way you think they should. There is a huge difference between drag and trans identities and I absolutely want to make that clear, there is a lot of cissexism within the drag community. Drag is a performance, you’re one gender in drag and another out of drag, while trans is an identity, when trans person takes off their dress or binder at the end of the day, they’re still trans. Drag is temporary, trans is permanent. Moving on to specifically drag, it blurs the lines of the gender binary by making a farce of these gender roles we have in our society, often camping up and over-exaggerating these expectations, and challenging the idea that boys should always have a masculine identity and girls should always be feminine. And drag is very performative, expressing gender in a way we don’t expect, as RuPaul says, “you’re born naked and the rest is drag.” In this quote, RuPaul seeks to critique the ways in which gender is a constant performance, an identity and appearance that one must constantly uphold, through self-policing, in order to fit into a designated role. But drag transcends and complicates the gender that one expects someone else to be and gives someone the experience to explore their own interpretation of how a boy or girl should act through what they have learned from their own experience. These greek identities are exactly what drag seeks to critique, the extreme masculinity of fraternities that is expressed through Brooks Brothers blazers, L.L. Bean khakis, and Vineyard Vines bow-ties in the most ridiculous color schemes I have ever seen is paired with the super femininity of sororities which manifests itself in Lilly Pulitzer dresses and Jack Rogers sandals, is almost camp within itself, being the extreme exemplar of what society thinks gender and sexuality should be. A black drag rearticulation of black fraternity performance complicates everything we think we know about race, class, sexuality, and gender within the greek system.

Diana Ross and her Supremes

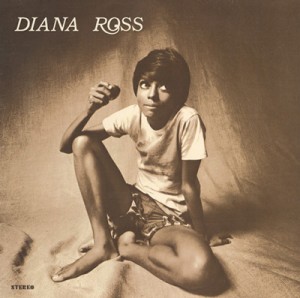

Diana Ross and her Supremes Diana Ross’ First Solo Album, Diana Ross

Diana Ross’ First Solo Album, Diana Ross