Portrait of George Gordon Meade, credit to Wikimedia Commons

By Devon Caldwell

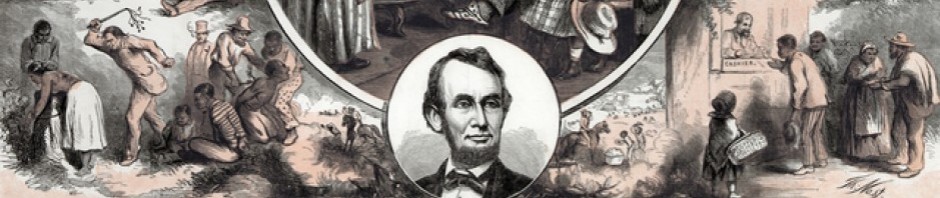

Dated only eleven days after the end of the Battle of Gettysburg, this “never sent, or signed” letter by President Abraham Lincoln voiced his displeasure with General George Meade, the commander of the Army of the Patomac. The Union was victorious during the three days of battle which took place between July 1-3, 1863. The battle was table-turning, so much so that Richard F. Welch explains that following the battle, “Lee’s army, dangerous as it was until the very last, would never again have the punch — in numbers, morale, quality and quantity of officers — that it took into Pennsylvania in June 1863.”

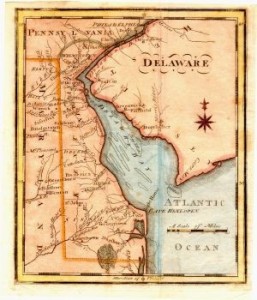

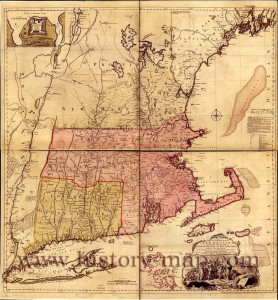

The 4th of July, 1863, saw the Confederate Army (led by General Robert E. Lee) retreat south toward Virginia. Lee’s plan was to cross the Potomac River, but there was a certain problem: the river had flooded at Williamsport, Maryland, and following the destruction of Lee’s pontoon bridge by Union General William H. French, the South was trapped (Wittenberg, et al, 160-161).

Left in Williamsport for nine days quite literally trapped, Lee and his men were finally able to cross the Potomac over the night of the 13-14. Lee had escaped back into Virginia and Lincoln was greatly displeased when he heard this news. Lincoln believed that by following Lee and his army, the Union could “have ended the war” (Lincoln, 14 July 1863). A letter sent by Lincoln only a few days earlier to Major General Henry Halleck confirms this belief, as Lincoln felt the “rebellion would be over” if “Gen. Meade can complete his work…, by the litteral (sic) or substantial destruction of Lee’s army…” (Lincoln, 7 July 1863). Of course, Lincoln soon learned that this would not happen.

A letter from Halleck — who himself had previously written to Meade to urge an attack on Lee and the remainder of his forces — to Meade written July 14 conveyed Lincoln’s “dissatisfaction” with Meade’s hesitance (Halleck, 14 July 1863). Meade’s same-day response to Halleck offers his own resignation: “the censure of the President…is…so undeserved that I feel compelled…to ask to be immediately relieved from the command of this army” (Meade, 14 July 1863).

From this point began Lincoln’s letter to Meade on July 14. Lincoln immediately attempted to soothe relations between he and Meade, and noted that he is “very — very— grateful” for Meade’s success at Gettysburg and rushed to apologize for the “supposed censure” that gave Meade “pain” (Lincoln, 14 July 1863). Using a form of empathy, Lincoln then compared the pain that Meade felt to his own “distress” that he felt must be “expressed.” Lincoln explained that he had evidence to believe that Generals Meade, Couch and Smith had no plan to pursue Lee insofar as to fight another battle, only to “get him across the river without another battle.” (Lincoln, 14 July 1863). Lincoln felt that all 3 Generals shared the blame for Lee’s successful retreat and later, criticized Couch and Smith for arriving too late to the Battle of Gettysburg.

Invasion of Maryland – General Meade’s army crossing the Antietam in pursuit of Lee, July 12, engraving for Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper by Edwin Forbes, Credit to Wikimedia Commons

Continuing on, Lincoln proceeded to defend his feelings very much as if he were in a courtroom, he even went so far as to use “the case” in his terminology (he will shortly hereafter use the terminology of “prossecution (sic)”, as well). Lincoln’s defense followed this logic: following the conclusion of the Battle of Gettysburg, as Lee and his men retreated, it seemed to Lincoln that the Union did not “pressingly pursue [Lee]” and while Lee and his men were “detained” by the flooded Potomac, although the Union army was able to be “upon” Lee again with “twenty thousand veteran troops” and “many more raw ones within supporting distance, all in addition to those who fought with you at Gettysburg…”, Lee was able to “move away at his leisure” (Lincoln, 14 July 1863) without an attack from the Union side. Meanwhile, Lincoln knew Lee received no new men, and therefore felt the Union soldiers had a decided advantage.

But was this the case? By this point, the Civil War had raged on for over two full years. Although the Battle of Gettysburg was a Union victory — a victory that Lincoln felt had the potential to end the war altogether — the casualties for both sides were tremendous. Modern figures have the total Confederate casualty figure at 28,063 (3,903 fatalities, 18,735 wounded and 5,425 missing) while the Union figure is 23,049 (3,155 fatalities, 14,529 wounded and 5,365 missing). So while the Confederate had a much higher aggregate total, the losses of the Union should not be discounted. It is very possible that General Meade felt that his army was in no shape to pursue Lee and fight another battle. Lincoln was merely a bystander to the death and destruction wrought at Gettysburg and as such, it is quite impossible that he had the firsthand knowledge like that of the Union generals. Although Lincoln may have felt that one final attack on Lee and his men at Williamsport could spell the end for the Confederacy, the Union general may not have felt that an attack was worth the risk or even at all feasible in its current battered state.

Regardless, Lincoln continued his letter by explaining the “misfortune” of “Lee’s escape” and the consequences thereof, while not neglecting the opportunity to once again assert that Lee was within the Union’s “easy grasp.” Lincoln feared that Lee’s retreat would prolong the war “indefinitely,” especially so as he knew that Meade would no longer have the same amount of troops available to him (“…few more than the two thirds of the force you had…”) as he pursued Lee back into Virginia. The President felt it “unreasonable to expect” a better opportunity for an attack to present itself “South of the river” than the one Meade had “last monday (sic)”.

Escape of the Army of Virginia, commanded by General Lee, over the Potomac River near Williamsport, painting by Edwin Forbes, Credit to Wikimedia Commons

Lincoln’s final short paragraph explained his purpose of writing: he learned that Meade learned of Lincoln’s own dissatisfaction second-hand, and wanted to personally explain why he felt such a way. Lincoln also wanted to be sure that Meade did not feel prosecuted or persecuted.

Again, it should be pointed out at this point that this letter went unsent by Lincoln and Meade remained in command of the Union army as Lincoln denied his resignation and furthermore, defended and supported Meade as shown in his letter to General Oliver O. Howard in which he wrote, “Gen. Meade has my confidence as a brave and skillful officer, and a true man” (Lincoln, 21 July 1863). This however, did not come before Lincoln seemingly admitted that his letter to Meade was written rashly: “A few days having passed, I am now profoundly grateful for what was done, without criticism for what was not done (emphasis author’s)” (Lincoln, 21 July 1863). Perhaps it was for this reason that the letter remained unsent. The President realized how emotionally and impetuously he had written this letter to Meade, and after a few days had passed, Lincoln realized it would be better if the letter were not sent at all. And so, the letter remained — as written on the envelope containing the letter — “never sent, or signed.”

References

“George G. Meade,” Civil War Trust. 2014. <http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/george-meade.html/>.

“July 14, 1863,” Shenandoah Valley Battlefields. 2013. <http://www.shenandoahatwar.org/150-Years-Ago-Today/1863-Entries-150-Years-Ago-Today/July-14-1863/>.

“Letter to Oliver O. Howard, July 21, 1863,” Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. University of Michigan. <http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln6/1:722?rgn=div1;view=fulltext/>.

“Letters from Union General George Gordon Meade,” Gettysburg College. Archived PDF. <http://www.gettysburg.edu/dotAsset/4a24eaf8-8a64-4d64-9f1e-12a6a2be2631.pdf/>.

“Lincoln’s Unsent Letter to George Meade,” Civil War Trust. 2014. <http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/primarysources/lincolns-unsent-letter-to.html/>.

“Lincoln Message Discovered at the National Archives,” National Archives. 7 June 2007. <http://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2007/nr07-108.html/>.

“Retreat from Gettysburg,” Civil War Trust. 2014. <http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/gettysburg/gettysburg-history-articles/battle-of-gettysburg-finale.html/>.

Wittenberg, Eric J., J. David Petruzzi, and Michael F. Nugent. One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4–14, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2008

Backcountry, n. –a rural area or wilderness

Backcountry, n. –a rural area or wilderness