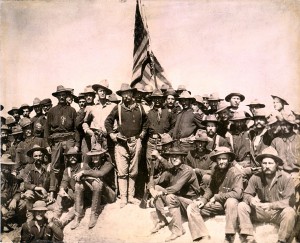

In his fascinating article on Theodore Roosevelt’s complicated nationalism, Gary Gerstle offers students in History 118 a series of challenging ideas. First, Gerstle explains how Roosevelt saw world history in terms of race conflict and believed earnestly in a hierarchy of racial categories –an idea embraced by most people in the nineteenth century. Gerstle then offers compelling details about Roosevelt’s famous experiences with the Rough Riders in the Spanish-America War. Yet instead of focusing on the standard romantic myths about the diverse and rowdy regiment, Gerstle demonstrates how Roosevelt celebrated his fellow Rough Riders at the expense of equally heroic black troops during that brief conflict in Cuba. Students who read this article should be able to identify Presley Holliday, a remarkable man who challenged Roosevelt’s version of the war’s history. Despite Roosevelt’s reluctance to acknowledge black equality, he did reach out to selected African Americans, such as Booker T. Washington. Gerstle goes even further, arguing that what he labels Roosevelt’s “civic nationalism” was a precursor to the spirit of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech and the modern civil rights ideal. He claims that Roosevelt was full of contradictions and that despite his belief in racial hierarchy, and his distaste for blacks and Chinese in particular, he was also a deep believer in the equality of American citizenship and the principle of the “Melting Pot.” Gerstle suggests that in this contradiction, Roosevelt embodied a Progressive Age in America that contained competing ideas of what it meant to be American. Students who need extra background on the diverse topics covered in this article should consult with the online textbook at Digital History, noting especially the chapters on Along the Color Line, Closing the Western Frontier, Huddled Masses, United States Becomes a World Power, and the Progressive Era.

In his fascinating article on Theodore Roosevelt’s complicated nationalism, Gary Gerstle offers students in History 118 a series of challenging ideas. First, Gerstle explains how Roosevelt saw world history in terms of race conflict and believed earnestly in a hierarchy of racial categories –an idea embraced by most people in the nineteenth century. Gerstle then offers compelling details about Roosevelt’s famous experiences with the Rough Riders in the Spanish-America War. Yet instead of focusing on the standard romantic myths about the diverse and rowdy regiment, Gerstle demonstrates how Roosevelt celebrated his fellow Rough Riders at the expense of equally heroic black troops during that brief conflict in Cuba. Students who read this article should be able to identify Presley Holliday, a remarkable man who challenged Roosevelt’s version of the war’s history. Despite Roosevelt’s reluctance to acknowledge black equality, he did reach out to selected African Americans, such as Booker T. Washington. Gerstle goes even further, arguing that what he labels Roosevelt’s “civic nationalism” was a precursor to the spirit of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech and the modern civil rights ideal. He claims that Roosevelt was full of contradictions and that despite his belief in racial hierarchy, and his distaste for blacks and Chinese in particular, he was also a deep believer in the equality of American citizenship and the principle of the “Melting Pot.” Gerstle suggests that in this contradiction, Roosevelt embodied a Progressive Age in America that contained competing ideas of what it meant to be American. Students who need extra background on the diverse topics covered in this article should consult with the online textbook at Digital History, noting especially the chapters on Along the Color Line, Closing the Western Frontier, Huddled Masses, United States Becomes a World Power, and the Progressive Era.

Allie Charles

Theodore Roosevelt was president of the U.S. at a time when many countries were in imperialistic and nationalistic modes; trying to gain new territory and create the best military. This strengthened Roosevelt’s desire of constructing the American race, one that would contain hard-working, ambitious, brave men. His prime example of the men that embodied this race were those who had rid early America of the “savages”.

To create the American race, Roosevelt was very open to mixing races; he believed that the mixture of races would “always produce peoples superior to those that had remained pure”. However, he had opinions on the groups of people whom he felt would better represent this race. Roosevelt favored those of European descent; African Americans and Asians were excluded they were inferior in his eyes. He would shut out these groups in various ways: in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act stopped the immigration of the Chinese. Roosevelt also limited the part that African Americans played in battle by not letting them become officers or have combat roles.

Roosevelt contradicted himself at many times about this issue. He believed very strongly of the promise that people would be welcomed and able to have the same rights as any other American citizen. He was very against discrimination, but he just truly felt that African Americans were not as superior. Roosevelt struggled with this ideology throughout his life.

Nguyen Ai Quoc

By the end of his life, Theodore Roosevelt had established a mixed legacy of civil rights and equality among African Americans. During his life, Roosevelt oscillated between praising specific individuals, to discriminating against the African American race as a whole. One notable, early example of Roosevelt’s interaction with African Americans was during the Spanish-American War. During the battles of Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill, Roosevelt’s all white regiment; the Rough Riders found themselves fighting alongside the all black 9th and 10th Calvary Divisions. After the war, Roosevelt praised the 10th Calvary’s conduct during the war. However, this praise was short lived and in the following year in 1899, Roosevelt wrote in Scribner’s Magazine that the black soldiers did not conduct themselves as well as white soldiers during the battle and that he even needed to draw his pistol on a group of Black soldiers to prevent them from fleeing the battlefield. This incident was disputed by a black 10th Calvary veteran, Presley Holliday. While he confirms that Roosevelt did draw his pistol on a group of black soldiers, Holliday says the group was merely following orders to carry the wounded back to the rear and to bring supplies back toward the front. He also recalls that Roosevelt apologized to his unit the next day. In the years after the war, Roosevelt had many more interactions with African Americans. During his Presidency, he had lunch with Booker T. Washington at the White House, dishonorably discharged 167 soldiers of the all black 25th Infantry Regiment, appointed a black man to the position of collectorship of Charleston, and excluded black delegates from the Progressive Party Convention in 1912. The only pattern that seemed to emerge from his treatment of African Americans was that while he thought the race as a whole was inferior, he did on occasion give praise to individuals or groups of individuals who distinguished themselves. In the end though, they would remain separate from the “melting pot” which he praised as one of America’s greatest strengths.

Elaine

Gerstle makes a well-supported argument regarding Roosevelt’s dilemma in defining American nationalism, especially given a more mixed American population. However, I found that Gerstle was over-zealous in making Roosevelt seem more tolerant in his social views. When explaining why Roosevelt accepted Jews and Irish-immigrants into the Rough Riders, while excluding blacks, Gerstle says this is a sign that “Roosevelt was becoming more liberal in his racial attitudes” (1287). In a footnote (15) on page 1287, Gerstle adds that Richard Slotkin disagrees with this conclusion. Slotkin writes that Roosevelt sought to mirror the “only those social types who had figured as parts of his mythic ‘Frontier’” (Gunfighter Nation, 104). Gerstle forgave Roosevelt his contradictory views, saying he was simply “a man of his time” (1307). However, for someone who espoused the ideals of New Nationalism and American idealism, Roosevelt did not include Americans who demonstrated the true American ‘frontiersman’ values that he admired, namely African-Americans. They had fought hard, with great tenacity and political cunning only a few decades before for their freedom, during the Civil War. While they were not fighting through untamed wild as the frontiersmen had done, African-Americans performed countless feats of bravery, and yet Roosevelt did not consider this part of American history at all. He did blacks further injustice by covering up their major part in the victory over Spain in 1898 (1292).

For these reasons I would argue that Roosevelt did not invite figures like Booker T. Washington to the White House for lunch because he saw him as equal to a white man, but rather, as in his bid for office 1912, Roosevelt was simply looking for political support. He denied blacks positions in the Progressive party in the South to get the white southern vote and tried to emphasize his supposed support for blacks in the North to get their vote as well (1304-5).

Garret Cerny

Gerstle, in this brief excerpt, defines the racialized structure of American nationalism in the period following reconstruction. In this progressive era, Theodore Roosevelt rose to the forefront of American politics as a leader of the Republican Party, and was inaugurated as president in 1901. In this expository, Gerstle delves thoroughly into Roosevelt’s role in the Rough Riders, the United States’ first volunteer cavalry. The men within this cavalry were organized by Theodore Roosevelt and emphasized in the process of choosing the appropriate men was Roosevelt’s goal of displaying the racial “melting pot” that characterizes the United States of America. According to Gerstle, 20,000 men applied to fill just 1000 positions and the men were incredibly diverse racial backgrounds ranging from Harvard athletes to western cowboys to Native American men: all in hopes of generating the finest, racially-diverse, All-American force. It was most curious that Roosevelt refused to accept black or Asian men into his mixed ethic group, perhaps due to his perceived belief that these men were not independent enough to fight or lead a military attack. Roosevelt’s ideas were contradicted when the Rough Riders fought alongside the all black 9th and 10th cavalries during the Spanish-American War when he witnessed leadership and bravery that he could not find in many of his Rough Rider troops. Although at many points during his career, Roosevelt praised the abilities of the African American, it seems that his overall view of this non-white race was one of perceived inferiority.

Devin Pratt

Although Theodore Roosevelt looked down on African-Americans and Asians, he held a very progressive view on race and nationalism for a man in the late 1800s. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, a volunteer Calvary of about 1,000 men, was largely comprised of western hunters and trappers, however there were also many european immigrants, hispanics, and American Indians. The diversity of the Rough Riders embodied what would come to be the American melting pot. Roosevelt referred to the mixed races of soldiers who served with him in his Rough Riders as a “splendid set of men” (Gerstle 1286), and embodied his belief that American nationality was a complicated classification that was not defined by a single color or ethnic background.

Not only were the Rough Riders ethnically diverse, but they were also diverse in their backgrounds. The regiment consisted of uneducated, rowdy backwoods Americans who were itching for a fight, and also young college graduates who brought civility and tactical minds to the unit.

The Rough Riders ended up fighting beside black soldiers in Cuba, where he developed a respect for their discipline and experience in combat. After the battle of Las Guásimas, the Rough Riders finally included black soldiers into their ranks and Roosevelt’s development into a liberal thinker on the subject of race was complete.

D'Andre Battle

Roosevelt’s Nationalism was certainly complicated and I also found it interesting how Gerstle mentions that this nationalism was rooted in Roosevelt’s Republicanism, which appeared to be a conservative one. In mentioning that Roosevelt believed in riding the government of any form of favoritism. This is after the party as a whole has taken the brunt of being alleged to have favored black people and policy during the Reconstruction era. Roosevelt’s Republicanism seems to be the kind that emerged after the Reconstruction era.

I also appreciate how Grestle displays the contradictions of Roosevelt’s nationalism. He does so by showing that Roosevelt only supported demographics that fit into his idea of nationalism, even if he did not agree with their views. Although feminists wanted to equally and just treatment relative to their male counterparts, Grestle mentions that Roosevelt only supported suffrage because it would “ultimately strengthen men, enhancing their ability to pursue national virtue and glory”. From this one can see that Roosevelt only made actions that, in the long term, supported his beliefs.

Penelope Bencosme

Theodore Roosevelt had a fixed idea when it came to who was superior and who was inferior. But he was open minded and welcoming. He believed, that due to scientific proof, the blacks were inferior to the whites simply because of their race, not because of their skin color. It does sound contradicting, however, that is what the article focuses on. Roosevelt strongly supported abolition and blacks, however, he believed that they didn’t have the strength necessary to be able to succeed. He believed that the whites had to deal with them because there were already too many of them in the US. He also really believed in the idea of the melting pot, that any person that was European or of European descent could come to the United States (the pot) and become part of the culture (melt) and then progress as a nation. Meanwhile he simply believed that blacks couldn’t mix. When he went to war against the Spanish he put together a regime called the Rough Riders and he included a diverse group of people that he believed were adventurous and strong enough to fight and defeat the Spanish, but none of them were black. While in Cuba he was accusing the blacks of being cowards and even pulled out a riffle to make sure that the black soldier got back to his place. However, someone went against that argument and said that the black man was responding to the call just as the white men were. In addition, Roosevelt thought that the Cubans were white and peace seekers and civilized just like the whites in the United States but he was shocked to find out that they were dark skinned and the Spanish who he thought were savages were actually white.