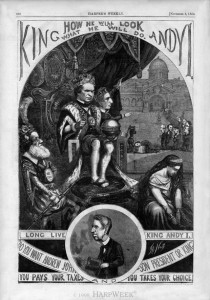

American politics has always been pretty rough, but perhaps no period was as bare-knuckled and partisan as the Reconstruction era. The confrontations involved more than just political combat between Democrats and Republicans. There were factions at odds with factions. Most notably, President Andrew Johnson waged war against Radical Republicans. These men had once been Unionist allies, but now found themselves in bitter disagreement over Reconstruction policy in the South. The result of this escalating conflict was the impeachment crisis of 1868. Thomas Nast, a leading cartoonist for Harpers Weekly depicted this crisis in a brilliant series of cartoons for the magazine. Please browse the selection of these cartoons and select one that seems to embody some of the most important insights from Eric Foner’s history of the period.

American politics has always been pretty rough, but perhaps no period was as bare-knuckled and partisan as the Reconstruction era. The confrontations involved more than just political combat between Democrats and Republicans. There were factions at odds with factions. Most notably, President Andrew Johnson waged war against Radical Republicans. These men had once been Unionist allies, but now found themselves in bitter disagreement over Reconstruction policy in the South. The result of this escalating conflict was the impeachment crisis of 1868. Thomas Nast, a leading cartoonist for Harpers Weekly depicted this crisis in a brilliant series of cartoons for the magazine. Please browse the selection of these cartoons and select one that seems to embody some of the most important insights from Eric Foner’s history of the period.

Author: Matthew Pinsker Page 2 of 3

Eric Foner and Olivia Mahoney have created a web-based exhibition hosted by the University of Houston that is designed to accompany his published work on Reconstruction. Students in History 118 should browse the image gallery of the sections of the exhibit entitled “Meaning of Freedom” and “From Slave Labor to Free Labor” in order to immerse themselves in the images and stories of the formerly enslaved people fighting to establish themselves as free American citizens. These types of visual exhibitions sometimes are even more effective than print sources in conveying the experiences of ordinary people in the past. What does this exhibit reveal about the everyday life of Reconstruction for the freed people?

Prince Rivers (1822-1887)

The story of Prince Rivers embodies many of the insights which Eric Foner tries to convey in the opening chapters of his book, A Short History of Reconstruction (2015 ed.). Rivers was a “contraband,” a wartime runaway slave, who fled behind Union lines along the South Carolina coast in 1862. He joined the Union army, serving in one of the first all-black regiments, and became something of a wartime celebrity. Later, during post-war Reconstruction, he became a political figure in South Carolina. The sad ending to his career, however, suggests how, as Foner put it, Reconstruction truly became, “America’s Unfinished Revolution.” You can read about Rivers in the following two posts at the Emancipation Digital Classroom. Try to use his story to punctuate Foner’s analysis about “Wartime Reconstruction” and the various “Rehearsals for Reconstruction.”

The end of the Civil War brought about the restoration of the Union and the end of slavery, but were these two objectives really one and the same? If so, does Abraham Lincoln deserve the lion’s share of the credit for melding them together? These are the types of questions that historians argue over. So did nineteenth-century Americans. One way to engage a fresh perspective on that debate is to examine what a commercial printer in Philadelphia did with a popular image following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. Here is what the image looked like that year:

Yet here is what the original illustration looked like in January 1863 when Thomas Nast first drew it for Harpers Weekly:

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

The difference is more than just color. Nast’s allegory for emancipation has now been subtly altered to give the martyred president a greater role.

Below is a photograph taken at Fort Sumter on Friday, April 14, 1865. That was a special day for the Union coalition –a kind of “mission accomplished” moment as Col. Robert Anderson returned with a delegation of notables, including abolitionists like Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and William Lloyd Garrison, to raise the American flag once again over the fort in Charleston harbor where the Civil War had begun almost exactly four years earlier.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

Note the cracked glass plate from this seemingly ruined photograph now in the collection of the Library of Congress. But look what happens to this image when it is digitized at a high resolution and then magnified.

That’s Rev. Henry Ward Beecher speaking on the afternoon of Friday, April 14, 1865, from what he called “this pulpit of broken stone.” Originally, scholars, using magnifying glasses, thought that William Lloyd Garrison was perhaps seated on Beecher’s left.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

But now we are confident at the House Divided Project that Garrison was actually seated in a special section on Beecher’s right, with other leading abolitionists and Lincoln administration notables.

It was obviously a moving, reflective moment for Garrison, one captured in this detail image above from right after the ceremony and by the little known story of his visit the following morning to see the grave of secessionist icon John C. Calhoun. You can read more about this episode here and here. Sometimes people are surprised by the stories that slip out of public memory and don’t make it into standard textbooks. The Garrison visit to South Carolina in April 1865 is certainly one of them, but another such lost tale involves a Dickinsonian named John A.J. Creswell, who was deeply involved in the final passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, which occurred in early January 1865. Here is the image that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper to celebrate that moment.

You will notice the trio of men in the lower right hand corner, obviously prominent figures according to the illustrator. We researched them here at the college and were thrilled to discover that one of them was a Dickinsonian. It turns out that these are three congressman from the Mid-Atlantic (from left to right) Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley, and John A.J. Creswell. We used a detail from that image for the cover of our first House Divided e-book, which profiles Creswell, a Dickinson graduate and Maryland politician who became one of the nation’s most important wartime abolitionists. Yet, he’s almost completely forgotten, not even mentioned in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Lincoln” (2012), which concerned passage of the amendment. You can download a free copy of Creswell’s biography, written by Dickinson college emeritus history professor John Osborne and college librarian Christine Bombaro, here. Ultimately, that might be the best way to rediscover the drama at the end of the Civil War –by seeing old stories from new perspectives.

The Living Room Candidate website, courtesy of the Museum of the Moving Image, has collected televised presidential campaign advertisements from 1952 to the present day. They offer a great window for understanding some key trends in US history since 1945.

The Living Room Candidate website, courtesy of the Museum of the Moving Image, has collected televised presidential campaign advertisements from 1952 to the present day. They offer a great window for understanding some key trends in US history since 1945.

Here is a pioneering TV ad from the 1952 campaign, presented in what was then popular movie newsreel style, for the Republican campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Think carefully about what the commercial is emphasizing –and also what it omits.

Compare that 1952 effort to this more polished, 1960 John F. Kennedy campaign ad, designed to invoke some of the more popular TV jingles of the 1950s.

Perhaps the most famous (or infamous) ad in the history of modern presidential campaigns appeared as a paid advertisement on TV only once –the so-called “Daisy ad” from 1964. Students should be able to explain what this ad was about, and why it was so powerful and controversial.

The Richard Nixon campaign in 1968 revolutionized the use of TV commercials in presidential contests, relying on them more than any other previous campaign organization. These two notable examples show some of the new techniques of advertising and also help highlight the shift in national climate since 1952.

The foreboding nature of those 1968 ads helps explain the strategy of calculated optimism behind this biographical short from the 1976 Jimmy Carter campaign. What’s also especially useful about this effort is how it captures several political and social trends from modern US history.

In the 1984 presidential election, Ronald Reagan won 49 out of 50 states. This commercial, known popularly as the “Morning Again in America” ad helps illustrate the broad appeal of the reelection campaign –and the sophisticated selling techniques of modern presidential politicking.

Here are video clips of Walter Cronkite’s original February 27, 1968 CBS Evening News Broadcast on the Tet Offensive and also an oral history from Cronkite about that pivotal TV moment recorded in 1999. Explain why this was such a pivotal moment in the history of US involvement in Vietnam.

The result of rising anti-war sentiment in the Democratic primaries and clear signposts of mainstream concern from sources such as Cronkite’s February special report convinced President Lyndon Johnson to announce on March 31, 1968 that he would not seek reelection after all. Here is the full broadcast of his address to the nation that evening. His remarks on quitting the presidential race begin around the 38 minute mark.

H.W. Brands labels his chapter on the 1950s as “The Golden Age of the Middle Class,” but even Brands seems unsure how much to believe in this label. Were the Fifties a “Golden Age,” or a new “Gilded Age,” or more ominously, still the “Dark Ages” for race and gender discrimination? There were certainly real signs of widespread growth and prosperity for the American nation in this defining post-war decade, but also significant underlying tensions and growing social problems. Trying to fit all of these trends into a single narrative is challenging, but students in History 118 should be able to explain the contours of the period with a series of notable examples.

The starting point might well be a consideration of population growth and the cultural consequences of the celebrated “Baby Boom.” US population soared between 1940 and 1960, from about 132 million people to over 180 million. The country gained about 30 million people during the 1950s alone –roughly equivalent to the entire population of Civil War era America. During this era of limited immigration (between the 1924 National Origins Act and the 1965 Immigration Act), the vast majority of these demographic gains came from an increased national birthrate. By 1964, Brands reports, four out of every ten Americans were Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964). The question for discerning students is how did all of these new children affect what Brands labels the “child-based culture” of the 1950s? One way to answer that question is by pointing to various trends in television, entertainment, music, sports, and other aspects of an emerging mass culture. But how much of this was a by-product of demographics or of new technologies remains an issue worth discussing.

Another way to interpret the period is by focusing on the economics of the Baby Boom, and considering how changing living and working patterns spurred important developments in post-war America. The 1950s certainly marked an era of industrial supremacy, big cities, interstate highways, and general stability for American capitalism, but also showed signs of a new more turbulent, suburban-oriented and service-based economy. During the early years of the post-war period, this combination of economic factors seemed to work wonders, with a greater equality of income than had been true across recent American history, but still, all was not equal in the society.

The most obvious inequality of the period was racial. The 1950s marked the resurgence of civil rights protests for the roughly 17 million American blacks who still endured Jim Crow in the South or faced other forms of persistent discrimination in the North. Brands illustrates the post-war civil rights movement by focusing on the impact of the two monumental Supreme Court decisions in the 1954 and 1955 Brown cases, and also on the 1955-6 Montgomery Bus Boycott. Students should be able to explain the significance of these milestone events.

Many historians, including Brands, also find a revealing linkage between the domestic civil rights movement and the international Cold War. In particular, during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the struggle to contain communism seemed to migrate toward what was increasingly called the “Third World,” as American policymakers sought (often unsuccessfully) to influence events in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Thus, questions of race and geopolitical strategy often overlapped. Regardless of the regional challenge of the moment, however, leading the globalized Cold War proved to be an enormous burden for American policymakers. Brands ends his sprawling chapter on the 1950s by quoting from President Dwight Eisenhower’s now-famous farewell address (January 1961), which invoked a warning about the rising “military-industrial complex.” Yet this warning, however “sobering” in Brands’s words, was complicated, because Eisenhower, the former general and sometimes belligerent commander-in-chief, was by no means prepared to stand down in the global fight against what he termed in that speech a “hostile ideology … ruthless in purpose and insidious in method.” Clearly, whatever had been so golden about 1950s was also competing against many ominous shadows.

Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton, Missouri in March 1946 surely “evoked divergent reactions in America,” as H.W. Brands claims in American Dreams (p. 32), but there can be little doubt that it struck a particular chord among key policymakers in the Truman administration, most notably with the new president himself. Students should listen to the opening of the famous speech and try to explain why Harry Truman (on stage, far left) found it so persuasive, remembering that less than just a year earlier, Churchill, Truman and Stalin had been together at the Potsdam conference, happily shaking hands as victorious allies.

Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton, Missouri in March 1946 surely “evoked divergent reactions in America,” as H.W. Brands claims in American Dreams (p. 32), but there can be little doubt that it struck a particular chord among key policymakers in the Truman administration, most notably with the new president himself. Students should listen to the opening of the famous speech and try to explain why Harry Truman (on stage, far left) found it so persuasive, remembering that less than just a year earlier, Churchill, Truman and Stalin had been together at the Potsdam conference, happily shaking hands as victorious allies.

Churchill’s stern 1946 warning about the Soviets highlighted a growing tension in superpower relations, a period that columnist Walter Lippmann described memorably as “The Cold War.” The US policy toward the Soviet Union which subsequently defined this Cold War period has come to be known as containment. State Department official George Kennan helped develop this containment doctrine, principally through two powerful documents, the so-called “Long Telegram,” and an anonymous article for the journal Foreign Affairs, titled, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.” Here is an excerpt from the now-famous 1947 article:

These considerations make Soviet diplomacy at once easier and more difficult to deal with than the diplomacy of individual aggressive leaders like Napoleon and Hitler. On the one hand it is more sensitive to contrary force, more ready to yield on individual sectors of the diplomatic front when that force is felt to be too strong, and thus more rational in the logic and rhetoric of power. On the other hand it cannot be easily defeated or discouraged by a single victory on the part of its opponents….In these circumstances it is clear that the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.

Students should be able to explain the significance of this passage and to articulate how key developments such as the Truman Doctrine (1947), Marshall Plan (1947) and Berlin Airlift (1948) help illustrate the initial application of containment principles. They should also be able to describe the views of early critics of US policy. It’s important to understand why figures such as Senator Robert Taft, a leading conservative, or Henry Wallace, a prominent progressive, questioned the rush toward Cold War. Some students might also find it helpful to view some of the placemarks in the map below (under the layer from Early Cold War, 1945-62), from the US Diplomatic History course here at Dickinson:

When Harry Truman became president in 1945 following the death of Franklin Roosevelt, he had seemed ill-prepared for the job. Yet according to H.W. Brands, “Truman grew into the presidency, far more quickly than most people, including himself, had considered possible” (p. 25). That growth helps explain why Truman prevailed in the 1948 election. He ran an aggressive campaign, calling a Republican-controlled Congress into special session, mobilizing core constituency groups within the New Deal coalition, and then conducting the last great “whistle-stop” campaign tour in American political history. Yet perhaps more important than anything else in this complicated four-way race, Truman managed by the fall of 1948 to appear to a majority of Americans as a safe choice for a commander-in-chief. It was a peacetime election, but the public was still in so many ways holding onto a wartime mentality. Arguably, nothing else better explains Truman’s success. At least to a majority of American voters, he appeared to be the right leader for a dangerous and fast-evolving Cold War era.

When Harry Truman became president in 1945 following the death of Franklin Roosevelt, he had seemed ill-prepared for the job. Yet according to H.W. Brands, “Truman grew into the presidency, far more quickly than most people, including himself, had considered possible” (p. 25). That growth helps explain why Truman prevailed in the 1948 election. He ran an aggressive campaign, calling a Republican-controlled Congress into special session, mobilizing core constituency groups within the New Deal coalition, and then conducting the last great “whistle-stop” campaign tour in American political history. Yet perhaps more important than anything else in this complicated four-way race, Truman managed by the fall of 1948 to appear to a majority of Americans as a safe choice for a commander-in-chief. It was a peacetime election, but the public was still in so many ways holding onto a wartime mentality. Arguably, nothing else better explains Truman’s success. At least to a majority of American voters, he appeared to be the right leader for a dangerous and fast-evolving Cold War era.

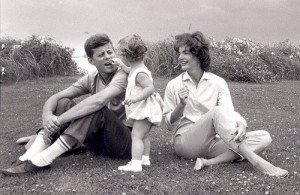

John F. Kennedy entered the White House with his young family in January 1961. He was the youngest man elected president of the United States, and the only Catholic so far. He only served for about three years, or a thousand days, but his legacy remains among the most widely discussed and debated. H.W. Brands focuses on two episodes more than any other: the Cuban Missile Crisis and the civil rights protests that escalated dramatically in the early 1960s. How would you assess Kennedy’s leadership in those pivotal areas? Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, seemed far less glamorous than Kennedy and yet he achieved more revolutionary change in domestic legislation than any president since Franklin Roosevelt. How did he accomplish so much so quickly during the mid-1960s? Which legislative actions were the most historically significant? Which proved to be the

John F. Kennedy entered the White House with his young family in January 1961. He was the youngest man elected president of the United States, and the only Catholic so far. He only served for about three years, or a thousand days, but his legacy remains among the most widely discussed and debated. H.W. Brands focuses on two episodes more than any other: the Cuban Missile Crisis and the civil rights protests that escalated dramatically in the early 1960s. How would you assess Kennedy’s leadership in those pivotal areas? Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, seemed far less glamorous than Kennedy and yet he achieved more revolutionary change in domestic legislation than any president since Franklin Roosevelt. How did he accomplish so much so quickly during the mid-1960s? Which legislative actions were the most historically significant? Which proved to be the  most controversial? Taken together, these various programs, dubbed “The Great Society” by Johnson and his admirers, represented a dramatic transformation in the role of the federal government. Take a moment and try to identify some of the biggest changes in American life and politics that had occurred in the century since the end of the Civil War.

most controversial? Taken together, these various programs, dubbed “The Great Society” by Johnson and his admirers, represented a dramatic transformation in the role of the federal government. Take a moment and try to identify some of the biggest changes in American life and politics that had occurred in the century since the end of the Civil War.

Was Senator Joseph McCarthy a lying, demagogue bent on destroying American civil liberties? Or was McCarthy instead a determined foe of dangerous Communist spies during the early 1950s? H.W. Brands calls McCarthy a “virtuoso of the political attack” who “tapped into anxieties current in the American psyche,” but also acknowledges that some of those “anxieties were perfectly rational” (52-53). Students in History 118 need to review the evidence themselves and offer their tentative conclusions. What were the principal causes of the intensifying “Red Scare” of the late 1940s and early 1950s? How should Americans describe this era and what lessons, if any, seem most relevant? The issue has special relevance for Dickinson College since the school was censured in 1956 by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) for firing an economics professor (Laurent LaVallee) for invoking the Fifth Amendment when he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities (HUAC) committee. See this article from the Chicago Tribune and also this background from the Lionel Lewis’ book, Cold War on Campus (available through Google Books). Brands also explains the impact of the Korean War on the Cold War and how containment doctrine began to evolve in dangerous new ways under President Eisenhower. Students in History 118 should be able to describe and explain the significance of covert operations in the mid-1950s, for example, and special items like the Doolittle report of 1954.