Here are three gateway images for the election of 1912:

- The candidates (identify and describe)

2. The issues (Explain the division among Progressives)

3. The Drama (Explain the meaning of this relic)

Here is a draft slideshow built from the work of students in History 211 showing scenes from Election Days past in American history.

“Twenty-four hours from the present writing the question will have been settled who is to be the President of the United States for four years from March 4, but during the interval between this time and that, when the result will be known, the American people will be in a state of excited expectancy.”

–National Republican, Nov. 7, 1876

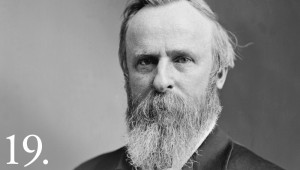

When Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and his wife Lucy went to bed on the night of Tuesday, November 7, 1876, Hayes was resigned to the fact that he had lost the 19th presidential election. By midnight, the Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden, was ahead by about 225,000 popular votes, with over 8.2 million votes cast. He was leading in the electoral vote with 184 out of the required 185 votes to secure the presidency,[1] and the Democrats were eager to pack their bags, evict the Republicans, and occupy the White House for the first time in 15 years. [2] Hayes stayed up to wait on returns from swing state New York, which he and advisors thought would decide the election. When a dispatch sent word that Tilden had a 50,000 vote lead in New York City, Hayes wrote, “from that point, I never supposed there was a chance for Republican success.” Rutherford Hayes wrote in his diary that night, “we soon fell into a refreshing sleep (…) and the affair seemed over.” [3]

19th President, 1877-1881. Courtesy of The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/1600/presidents/rutherfordbhayes.

However, within a few hours, controversial vote tallies came in from four states. Both the Democrats and the Republicans accused each other of fraudulent voting practices and a fierce battle for the presidency ensued, but predominantly between Democrat and Republican Party leaders and not between Hayes and Tilden themselves. With a reputation as an honest man, Hayes did not immediately contest the election, being more worried about the legitimacy of recounting the votes than winning. [4] Although Rutherford B. Hayes remained uninvolved in the election day voting fraud and subsequent recounts, both Republican Party leaders and Democrat leaders revealed intense party competition and corruption of the time period by prioritizing an 1876 party win over a just democratic election, and challenging the right to a fair vote.

While Hayes slept, convinced of his defeat, former Republican congressman Daniel Sickles, stopped at the Republican headquarters to check on the voting return numbers. He quickly realized that if Hayes secured the seven electoral votes from South Carolina, eight electoral votes from Louisiana, and four electoral votes from Florida, all of which had not come in yet, then Hayes’ count would increase from 165 to tie Tilden at 184. Seeing Zachariah Chandler, the Republican Party chairman, in a drunken stupor in his office, Sickles decided to send telegrams in Chandler’s name to several Republican leaders in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida to alert them of the importance of those states’ electoral votes. He received reply, “All right. South Carolina is for Hayes” from Governor Daniel Chamberlain at 3:00 am. [5] Sickles’ dishonesty marked the beginning of a duplicitous election day, although without his telegrams, Hayes may have had no chance at winning.

When Hayes awoke on the 8th, he wrote a letter to his son at Cornell reflecting on his loss. He graciously accepted the outcome, but was disappointed in not having a chance “to establish Civil Service reform, and to do good work for the South” as part of his campaign platform. [6] Both presidential candidates were popular because of their integrity and desire for reform. Hayes, the governor of Ohio, had supported Reconstruction efforts and the ratification of the 15th Amendment, and he wanted to continue to improve the conditions of African Americans in the South. He didn’t smoke, he didn’t drink, and was a volunteer during the Civil War. His opponent, Tilden, was the governor of New York, and known for helping to dissolve the corrupt Tweed Ring Democrat group. Both Hayes and Tilden were appealing presidential figures who contrasted President Grant’s administration, which was tainted with bribery and scandal. Ironically, the election day proceedings did not meet the virtuous standards of its candidates. [7]

Not long after writing the letter to his son, Hayes was informed that he had won the West Coast and could still win the election. As the sun rose that morning, the president-elect was undetermined, and copies of the National Republican circulated in Washington DC shouting the headline, “Suspense! Possibly Tilden, Hopefully Hayes (…) Reports Very Conflicting, Some Probably Falsified.” [8] The hesitation in declaring a president-elect was due to inconsistent popular vote counts in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, as well as a questionable electoral voter in Oregon. In the 1870s, voting ballots were actually “party tickets,” printed by political parties and containing a list of all candidates for that party. They might have been printed in a color to represent the party and to aid illiterate voters. These tickets made voting fraud simple, as multiple tickets could easily be folded up and submitted by one person. [9] In addition, Hayes believed that the election had been stolen from him through unconstitutional voting restrictions in the South, primarily through limiting African Americans’ and white republicans’ ability to vote by racist terrorist groups and registration requirements, but he was prepared to “accept the inevitable” with “composure and cheerfulness.” [10]

Both parties certain that they had won the states, they each submitted separate vote tallies to Congress. In Florida, out of 47,000 votes, Republicans reported a 922 vote margin with Hayes ahead, and denounced the Democrats for restricting African Americans’ voting rights through intimidation tactics and bribery [11] in addition to tricking illiterate voters by printing Democratic ballots with a Republican symbol. [12] So convinced that they had won the election, by November 9, the Republican newspaper National Republican proclaimed that Hayes had won with the full page headline “Glorious News!” [13]

On the other hand, Democrats were just as confident that Tilden was the winner. In Florida, they claimed that there was a 94 vote margin in favor of Tilden, and contended that Republicans had smeared ink on ballots in a pro-Tilden county to discredit those votes. [14] Voting officials accused opposing parties of stuffing ballot boxes with false votes, and that in some counties, the number of votes surpassed population. To add to the already high level of deception, allegedly the Democratic National Committee in LA claimed that the Republicans suggested that there would be a guaranteed Democratic popular majority in exchange for $1 million. [15] In Oregon, the Democrat Governor La Fayette Grover noticed that one of the Republican electors was federally employed at a post office, and therefore ineligible to be an elector. He appointed a new Democrat elector, and although Hayes still won the electoral votes for Oregon, the Democrats responded by crying fraud. [16] In Louisiana, citizens were informed that Democrats won the election. A Democrat newspaper, the Louisiana Democrat, printed on November 15, “The Republican Party is Dead!” in celebration of a Tilden majority. [17] A week after election day, inconsistent reports announced either Hayes or Tilden as the president-elect, and both parties unequivocally advocated for their own candidate.

The level of cheating on both sides was undoubtedly high. To attempt to reach a verdict, Republican officials under Grant set up “returning boards” in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida to recount disputed votes. Besides sorting through problems related to voter activity, bribery, and other depravities, there was the issue of how to count the controversial votes. Hayes told friend US Senator Carl Schurz that he was concerned that “in the canvassing of results there should be no taint of dishonesty,” and wrote to John Sherman, who was a Republican statesman dispatched to Louisiana, “we are not to allow our friends to defeat one outrage and fraud by another…there must be nothing crooked on our part.” [18] Hayes was dismayed at the amount of underhanded political dealing contributing to the election, and acknowledged that the democracy set up by the Founding Fathers was failing; he wrote in his diary on December 7, 1876, “A contest ruinous to the country, dangerous, perhaps fatal to free government may grow out of [the fraud]. I would gladly give up all claim to the [presidency], if this would avert the evil without bringing on us a greater calamity.” [19] Hayes soon realized that his protests were in vain; party leaders were determined to amass as many votes as possible and the Republican Party was adamant about winning the election by any means necessary.

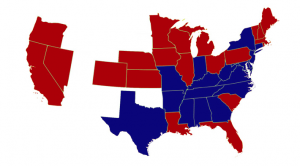

Map of Electoral Votes in 1876 Presidential Election. Red represents votes for Hayes and blue represents votes for Tilden. Courtesy of the American Presidency Project.

Not until 4:10 am on March 2, 1877 was election day truly over. [20] Ultimately, Rutherford Hayes won the election. Republican candidates Hayes and running mate William Wheeler were given 4,033,497 popular votes, or 48%, and 185 electoral votes. Democrats Tilden and Hendricks were given 4,288,191 popular votes, or 51%, and 184 electoral votes. In spite of losing the popular vote, all disputed electoral votes from South Carolina, Louisiana, Florida, and Oregon were awarded to Hayes. [21]

Fraudulent votes and political party intervention at the state level corrupted the election and made it effectively impossible to determine a true winner, and Democrats started calling Hayes “Rutherfraud” and “His Fraudulency” because they were furious at how he “stole” the election. [22] Hayes expressed in his inaugural speech on March 5 that he, “owed his election to office to the…zealous labors of a political party” because it was due to the interventions of his party’s supporters that he was eventually elected. [23] The election day events of 1876 exposed the democratic-republican government experiment as an imperfect system. The election demonstrated that election day voting needed continual adjustment to avoid biased votes and false votes from political parties, and set the stage for later constitutional debates over the right to vote and the right to have a vote counted.

[1] Richard Wormser, “Hayes-Tilden Election (1876),” The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, PBS, 2002. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_election.html

[2] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[3] Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume III, The Disputed Election–Electoral Commission–Selection of Cabinet, 1876-1877, Nov. 11, 1876, Ohio History Connection. Retrieved Nov. 4, 2016 from http://apps.ohiohistory.org/hayes/results.php?page=4&ipp=20&&searchterm=election

[4] Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[5] “The Political Situation,” Finding Precedent: Hayes vs Tilden, HarpWeek, 2008. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://elections.harpweek.com/09Ver2Controversy/Overview-1.htm.

[6] Rowland L. Young, “The Year They Stole the White House,” ABA Journal 62 (1976): 1460. [Google Books]

[7] Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Rutherford B. Hayes: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center. Accessed Oct. 30, 2016 from http://millercenter.org/president/biography/hayes-campaigns-and-elections

[8] The National Republican, (Washington DC), Nov. 8, 1876. [Library of Congress] Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86053573/1876-11-08/ed-1/seq-1/

[9] “The History of the Paper Ballot,” Fair Vote. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://archive.fairvote.org/righttovote/pballot.pdf

[10] Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume III, The Disputed Election–Electoral Commission–Selection of Cabinet, 1876-1877, Nov. 12, 1876, Ohio History Connection. Retrieved Nov. 4, 2016 from http://apps.ohiohistory.org/hayes/results.php?page=4&ipp=20&&searchterm=election

[11] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[12] Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[13] The National Republican (Washington DC), Nov. 9, 1876. [Library of Congress] Retrieved Nov. 6. 2016 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86053573/1876-11-09/ed-1/seq-1/.

[14] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[15] Gilbert King, “The Ugliest, Most Contentious Presidential Election Ever,” Smithsonian.com, Sept. 7, 2012. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-ugliest-most-contentious-presidential-election-ever-28429530/?no-ist.

[16] S. Mintz and S. McNeil, “The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876,” Digital History, 2016. Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3109.

[17] The Louisiana Democrat [Alexandria, LA], Nov. 15, 1876. [Library of Congress] Retrieved Nov. 6, 2016 from http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82003389/1876-11-15/ed-1/seq-2/.

[18] Quotes in Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[19] Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary of Rutherford B. Hayes, Volume III, The Disputed Election–Electoral Commission–Selection of Cabinet, 1876-1877, Dec. 7, 1876, Ohio History Connection. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2016 from http://apps.ohiohistory.org/hayes/results.php?page=5&ipp=20&&searchterm=election

[20] Ari Hoogenboom, “Chapter 17: Disputed Election,” Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President (University Press of Kansas, 1995). Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016 from http://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/disputed-election-by-ari-hoogenboom/

[21] John Woolley and Gerhard Peters, “Election of 1876,” The American Presidency Project, 2016. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2016 from http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1876

[22] Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Rutherford B. Hayes: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center. Accessed Oct. 30, 2016 from http://millercenter.org/president/biography/hayes-campaigns-and-elections

[23] Rutherford B. Hayes, “Inaugural Address of Rutherford B. Hayes,” March 5, 1877. Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, 2014. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2016 from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/hayes.asp

By Ryan Schutte

On November 3, 1874, Captain A.S. Daggett of the 2nd U.S. infantry sat at his hotel window and watched horrified as bloodshed ensued outside the polls on the main street of Eufaula, Alabama on election day. An altercation outside a polling station between a black Republican, Milas Lawrence, and white Democrat, Charles E. Goodwin, quickly turned into a massacre after Lawrence was stabbed in the shoulder by Goodwin’s companion, William Dowdy. Prepared for conflict, unofficial white militia men shouted, “Fall in Company A; Fall in Company B,” and began firing an estimated 500 shots into the mass of unarmed black men on the street. When the dust had settled, seventy-five men were found wounded and seven dead. More life was lost later that night in the neighboring town of Spring Hills, when Democrat intruders broke into the house of the Republican city court judge Elias Hills and opened fire, killing his 16-year-old son, Willie. Overshadowed by the carnage of that day was the large-scale destruction of ballot boxes, the theft and burning of hundreds of casted ballots, as well as the denial of thousands of black men from the polls. Democrats swept the county elections, and symbolic of the rest of the nation, had a new party representing their district in the House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War. The events of Eufaula in 1874 exemplify the militaristic arm of the Democratic Party that was taking hold in southern politics, and paired with inadequate federal response, effectively eliminated blacks’ newfound rights granted by the 14th and 15th amendments [1].

Sitting just below America’s Black Belt along the Chattahoochee River, Eufaula, like the rest of the nation experienced a period of expansion in the right to vote with the Civil War’s end [2]. Despite opposition from Southern states and President Andrew Johnson, the majority Republican Congress passed the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing newly freed blacks citizenship, due process, equal protection under the law, and, most importantly, the right to vote [3]. The democratization of the right to vote was, by no means, accepted without resistance and in a petition sent to Congress, Alabama conservatives referred to the newly enfranchised blacks as, “…ignorant generally, wholly unacquainted with the principles of free Governments, improvident, disinclined to work…dishonest, untruthful, incapable of self-restraint, and easily impelled…into folly and crime…” [4]. By 1874, “White Northern disillusionment with Reconstruction” had set in, and the nation was in the midst of an economic downturn like never before. As a result, black civil rights expansion became increasingly unpopular, and southern blacks were left alone in the fight to protect their newfound voting rights [5].

Throughout the summer of 1874, racial and political tensions in Eufaula had reached its climax as white conservatives hoped desperately to redeem political control from the Republican coalition of carpetbaggers, scalawags, and enfranchised blacks. To Barbour County Democrats’ dismay, influence from the opposition political alliance often resulted in the election of Republican candidates in local elections– their current representative in Congress a leading black politician, James Rapier [6]. Rapier, born free in the slaveholding south in 1837, won his seat in December of 1873 and worked hard during his tenure in the defense of black rights. In his first address to Congress, Rapier reaffirmed this stance as he proclaimed, “I cannot willingly accept anything less than my full measure of rights as a man, because I am unwilling to present myself as a candidate for any brand of inferiority.” Consequently, Alabama’s white conservatives were determined to win the November congressional election in order to save the state from “Negro Rule” [7]. In June of 1874 at the state convention, Democrats nominated former Confederate, Jeremiah Williams, for the 2nd Alabama congressional seat and adopted the Pike County Platform [8]. The platform read:

“[Nothing] is left to the white man’s party but social ostracism of all those who act, sympathize or side with the negro party, or who support or advocate the odious, unjust, and unreasonable measure known as the civil rights bill; and that from henceforth we will hold all such persons as enemies of our race, and we will not in the future have intercourse with them in any of the social relations of life [9].”

In essence, the Alabama Democratic platform encouraged the ostracism of white Republicans in hopes that deprivation of a satisfactory social life could change their opponents’ voting behavior or force them to move [10]. Later that Summer, local Democrats took more extreme measures to defeat the Republicans when they formed the “White Man’s Club of Eufaula.” Similar to the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan, members of the organization attempted to force local black voters to pledge loyalty to the Democratic party [11].

On top of the pressures provided by the Democrats, a faction within the local Republican Party had materialized over the pending impeachment of Judge Richard Busteed. Despite his determination to stay out of the conflict, Rapier was forced to give in when armed protestors showed up at the Republican nominating convention in August, threatening violence unless their demands were met. To many voters, Rapier’s surrender to the violent faction of Republicans reeked of corruption, and following the event one southern newspaper noted the Democrats disapproval of the “bargain” [12] . In a political misstep, Rapier went back on his pledge a few days later, and leading up to the election, his chances of earning a second term were in question [13].

Nothing clouded the political landscape more than the growing “atmosphere of violence” as election day neared, and according to historian, Melinda M. Hennessey, city court judge, Elias Keils “personified” the political struggle in Eufaula. Keils, a former secessionist, but now a middle-aged Republican leader in Eufaula, had been elected to the city court in 1870. In his four years as city court judge, Keils faced significant political opposition from the Democratic party and was accused of protecting guilty blacks in the county. As the midterm election of 1874 neared, Keils recognized the growing political and racial tensions throughout Bourbon County; and, seeking support and protection, wrote to Alabama attorney general, Benjamin Gardner, as well as U.S. Marshall, Robert W. Healy, on several occasions. Finally, less than two weeks before the election, the marshall answered his pleas, and a company of soldiers led by Captain A.S. Daggett was sent to oversee the elections. However, just as the soldiers from the U.S. 2nd infantry arrived in Barbour County, their ability to aid the election was severely restricted by General Order No. 75. General Irwin McDowell, Commander of the Department of the South and Captain Daggett’s superior, gave the order, limiting uses for Army troops to enforce writs of U.S. courts and protect Internal Revenue Department agents. Despite Captain Daggett’s protests, he and his troops were essentially powerless, and Keils and the Republican party were forced to proceed with the election unprotected [14].

Despite the lack of protection, black voters were prepared to use strength in numbers, and the night before the election hundreds gathered on the outskirts of Eufaula to prepare for election day. Republican leaders, George H. Williams, Henry Frazer, and Edward Odom organized voters, handed out Republican ballots, and gave orders to travel unarmed on their march to the polls, to “avoid the slightest excuse for white violence…” [15]. On the morning of November 3rd, an estimated 1,500 men marched into the town ready to cast their votes at the town’s polling place. Throughout the morning, blacks and whites, Republicans and Democrats, cast their votes peacefully. However, at 1 o’clock, Milas Lawrence’s and Charles Goodwin’s paths crossed as Goodwin and his fellow Democrats attempted to force an underaged black boy to vote the Democratic ticket. Once the first gunshot sounded, white men ran to their predetermined stations on either side of the street and to second-floor shops above. After about one minute and an estimated 500 gunshots, with the attacked laying in the street, former Confederate brigadier general, Alpheus Baker, yelled with the rest of the men, “Let the Yankees come. We are ready for them” [16]. The violence and destruction in Eufuala on November 3rd kept many blacks and Republicans from the polls and hundreds of casted ballots for the Republican ticket were destroyed. In the end, the Alabama 2nd congressional district went to the Democrats as Jeremiah Williams won the election by 1,056 votes and took his seat at the House of Representatives. After an unsuccessful appeal over the validity of the election, James Rapier was forced to forfeit his position and the election of Williams was confirmed [17].

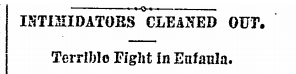

Headline in Georgia Weekly Telegraph a week after Eufaula Election Riot. Courtesy of Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

In the aftermath of the Eufaula Riot, Congress launched an investigation into the events that transpired on November 3rd. When the evidence had been collected, the majority determined it was a “premeditated affair to intimidate black voters…” [18]. Southern newspapers, however, responded quite differently, and placed blame on the Eufaula’s black population. A November 10th article from the Georgia Weekly Telegraph twisted the story saying, “The difficulty grew out of the abuse of a negro… by several Radical negroes, chief among whom was one very bad negro named Milas…With an oath against the whites, and daring them to come on, he drew out his pistol and fired”[19]. Not only did the source reverse the attackers and the victims, but made sure to refer to the whites responding to the attack as “gentlemen.” Similarly, another account from a Mississippi paper, The Hinds County Gazette, gave whites a heroic and patriarchal role in the riot, where whites saw the assault and “would not allow it to be done” [20]. The inaccuracy and racial bias of these two accounts demonstrate the growing Democratic influence over the once Confederate states in the years following the war. The lack of consequences for the guilty party following the Eufaula Riots and the ability of Democrats to twist the narrative to their own benefit opened the doors for further acts of violence that would eventually eliminate Republican support and the black vote in the South.

Testimony from Captain A.S. Daggett Describing His Orders and the Riot

Although violence like that of Eufaula was not a commonplace in the 1874 election, the electoral outcome held true throughout the nation. Ninety-four Democratic congressional candidates around the country beat out their Republican adversaries in 1874, and took a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War [21]. The election marked a success for the Democratic party, not only in congressional seats, but in their newfound ability to control the black vote. While Republicans maintained control over the Presidency and the Senate, the midterm election of 1874 made clear that control over the South was slipping. The election signaled that with little to no federal oversight, southern state and local governments had free reign over elections and could implement policies to nullify the designed effects of the 14th and 15th Amendments. 1874 marked the beginning of the end of the black right to vote in the South– a right that would take almost a century to recover.

[1] Hennessey, Melinda M. “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 38, no. 2 (1976): 118-120. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

Owens, Harry P. “The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” The Alabama Review 16, no. 3 (1963): 233. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

Wilhelm, Blake. “Election Riots of 1874.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. November 6, 2009. Accessed November 1, 2016. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2484.

[2] “Eufaula, Alabama.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufaula,_Alabama#Geography.

[3] Pinsker, Matthew. “Understanding the ‘Strange Odyssey’ of the Fifteenth Amendment.” September 20, 2016.

[4] Keyssar, Alexander. The right to vote : the contested history of democracy in the United States. n.p.: New York : Basic Books, 2009., 2009. 73-74, 84.

[5] Robertson, Andrew W. “The Continuing Struggle for Full Rights” In Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History, edited by Andrew W. Robertson, 26-27. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010. doi: 10.4135/9781608712380.n239. [Google Scholar]

[6] Wilhelm, 2009.

Hennessey, 113.

[7] Rabinowitz, Howard N. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982. 83-84.

Hennessey, 112.

[8] Hennessey, 114.

“Democratic Party Platform of Pike County, Alabama (1874).” Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 4, 2016. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/democratic-party-platform-pike-county-alabama-1874.

“Williams, Jeremiah Norman, (1829-1915).” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Accessed November 6, 2016. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000512.

Rabinowitz, 83-84.

[9] “Democratic Party Platform of Pike County, Alabama (1874).” Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 3, 2016. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/democratic-party-platform-pike-county-alabama-1874.

[10] Hennessey, 114-115.

[11] Wilhelm, 2009.

[12] “By Telegraph.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger [Macon, Georgia] 15 Sept. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

[13] Rabinowitz, 85-86.

[14] Hennessey, 112.-113, 116, 119-120.

Owens, 231-232, 226.

[15] Hennessey, 116-117.

Owens, 232-233.

[16] Hennessey, 117-119.

Owens, 233-234.

[17] Rabinowitz, 86.

[18] Hennessey, 123.

[19] “Intimidators Cleaned Out.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger (Macon, Georgia), November 10, 1874. Accessed November 3, 2016. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

[20] “The Election Riot at Eufaula, Ala.” Hinds County Gazette [Raymond, Mississippi] 11 Nov. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 3 Nov. 2016.

[21] “United States House of Representatives Elections, 1874.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_House_of_Representatives_elections,_1874.

Bibliography

“By Telegraph.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger [Macon, Georgia] 15 Sept. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

“Democratic Party Platform of Pike County, Alabama (1874).” Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 4, 2016. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/democratic-party-platform-pike-county-alabama-1874.

“Eufaula, Alabama.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufaula,_Alabama#Geography.

Hennessey, Melinda M. “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 38, no. 2 (1976): 112-25. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

“Intimidators Cleaned Out.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger (Macon, Georgia), November 10, 1874. Accessed November 3, 2016. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

Keyssar, Alexander. The right to vote : the contested history of democracy in the United States. n.p.: New York : Basic Books, 2009., 2009. Dickinson College Library Catalog, EBSCOhost (accessed November 3, 2016).

Owens, Harry P. “The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” The Alabama Review 16, no. 3 (1963): 224-38. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

Rabinowitz, Howard N. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982. 83-84.

Robertson, Andrew W. “Congress.” In Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History, edited by Andrew W. Robertson, 904-909. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010. doi: 10.4135/9781608712380.n239. [Google Scholar]

“Strategic Politicians and U.S. House Elections, 1874–1914.” The Journal of Politics, 2005., 474, JSTOR Journals, EBSCOhost(accessed November 4, 2016).

“The Election Riot at Eufaula, Ala.” Hinds County Gazette [Raymond, Mississippi] 11 Nov. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 3 Nov. 2016.

“United States House of Representatives Elections, 1874.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_House_of_Representatives_elections,_1874.

Wilhelm, Blake. “Election Riots of 1874.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. November 6, 2009. Accessed November 1, 2016. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2484.

“Williams, Jeremiah Norman, (1829-1915).” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Accessed November 6, 2016. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000512.

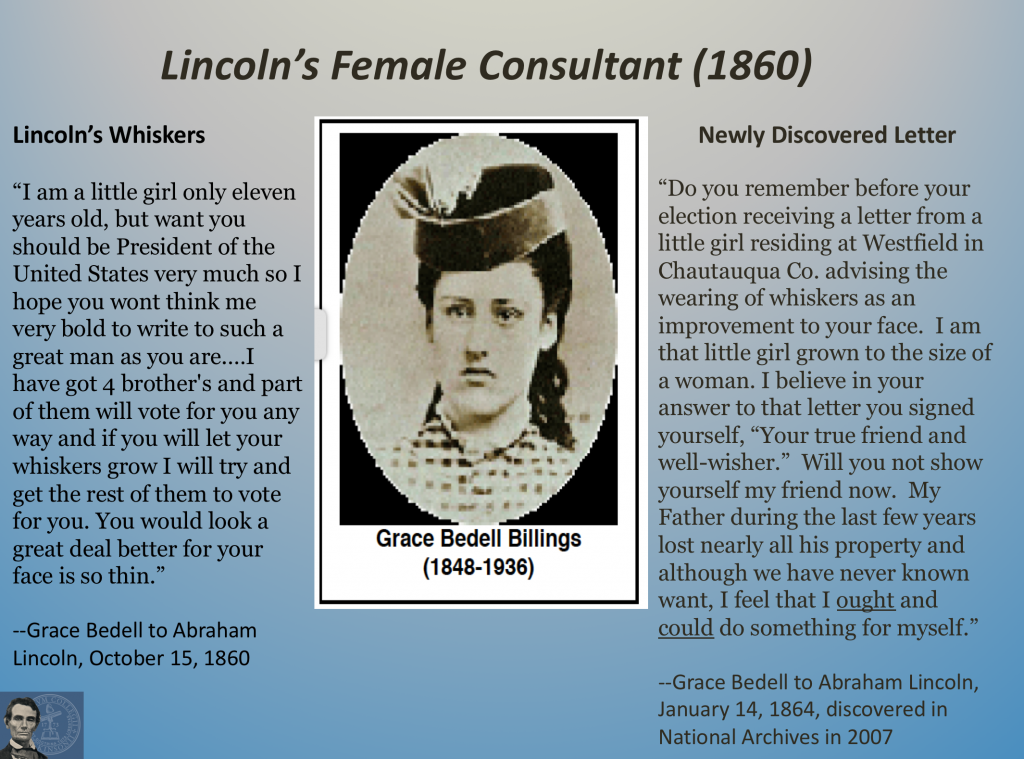

Why did the results of the 1860 election trigger Civil War?

The election of 1860 was the only presidential election in American history that resulted in widespread violence. Seven states in the Deep South, led by South Carolina, refused to accept the results of the contest that elevated the new Republican Party and its nominee, Abraham Lincoln, into national power. Secession began in December 1860 (with an ordinance drafted by Dickinson College graduate John A. Inglis) and escalated into the organization of the Confederate states in February 1861 and then full blown Civil War by April when President Lincoln refused to back down in the face of assaults on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor.

Thus, the 1860 contest stands alone in American history. Yet how should students best understand its meaning? In History 211, students will look carefully at the so-called “campaign” of Abraham Lincoln, through study of his 1859 autobiographical sketch and his October 1860 letter to a young girl named Grace Bedell. C-SPAN filmed a previous version of this particular class in 2010. You might want to check it out (and pay particular attention to the late student arriving at the beginning of the video…).

For those who need additional background on the contest, please check out the following resources:

CNN calls the 2000 election for Gore, then for Bush, and then as too close to call, November 8, 2000:

ABC News describes Florida recount problems on November 12, 2000:

ABC News on the Gore v. Bush per curiam decision on the evening of December 12, 2000:

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén