The River of Roosevelt – Rio Da Roosevelt – runs 400 miles through western Brazil, finally meeting the Amazon River. It is among the harshest tributaries of the Amazon, and until less than one century ago, was thought to be unchartable by all but the Amazonian natives. Unsurprising to those who knew him and to those who study him, President Theodore Roosevelt thought differently. Equally unsurprising, Teddy Roosevelt would soon seek to ‘do’ differently.

Considering the rich and varied narrative of his own life, it is not unlikely that Teddy Roosevelt’s plans for the River of Doubt were hatched late on the night of November 5th, 1912.

His November 5th would have seemed quiet from all perspectives: a day spent at home, closeted away from the public and the press with staff, friends, and family.

In the life of a former Colonel in the Spanish-American War, New York City Police Commissioner, and two-term President of the United States, November 5th was an exceptionally quiet day. On this day, of course, Theodore Roosevelt was not merely ‘former President;’ he was the Progressive – colloquially, Bull Moose – Party’s nominee for the White House, and on the night of November 5th, he would see his hopes for a third term in office stand against those of Democratic and Republican candidates.

The New York Times reported that Theodore Roosevelt watched 1912’s election day unfold from his home on New York’s Oyster Bay Harbor. He spent much of the morning avoiding all manner of publicity, whether it was a local trying to catch a glimpse of a famous neighbor or a reporter trying to get an exclusive scoop. The Boston Daily Globe reports Roosevelt finally leaving Sagamore Hill for an engine house on the eastern side of Long Island, where he would cast his ballot. The Globe’s reporter ascribes anxiety to the crowd observing Roosevelt at the polls, stating “he took so long that some of his party wondered whether he could be scratching candidates.” Exiting the booth, he took a few minutes to speak with a crowd of supporters and voters, before returning home to Sagamore Hill. A few hours later, in what would be his last appearance as a candidate before votes were finally tallied, he met with Progressive Party secretary George Perkins. Perkins was so surprised as to be “peeved” at the lack of interest displayed by Roosevelt in his election, having spent a significant portion of the conversation with him listening to gossip about Sagamore Hill and the nature surrounding it.

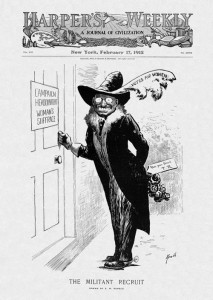

Regardless of Roosevelt’s personal interest in the election of 1912 – and his true feelings on the subject will likely forever remain a mystery – this was a formative election year in United States history. It marked the beginning of the end, as Alexander Keyssar explains in The Right to Vote, of female disenfranchisement from the vote, with states from Oregon to Illinois beginning to allow woman to participate in Presidential elections. Equally important, it marked the last truly viable third-party candidacy in a Presidential election until Ross Perot in 1992. Though Roosevelt sought to remove a Republican President he saw as far too conservative, he incidentally inserted a Democratic President he likely saw as far too liberal, all the while bolstering the unchallenged sanctity of the two-party system.

More than a year later, as the former President set out to chart a different kind of course in the Amazon, he may have been less interested in avoiding the American public’s eye or interest, and more focused on forgetting the story of his candidacy for a third term in his own heart and mind.