Who was the most compelling US diplomat of the Second World War?

CHAPTER 13: “Five Continents and Seven Seas”: World War II and the Rise of American Globalism, 1941-1945

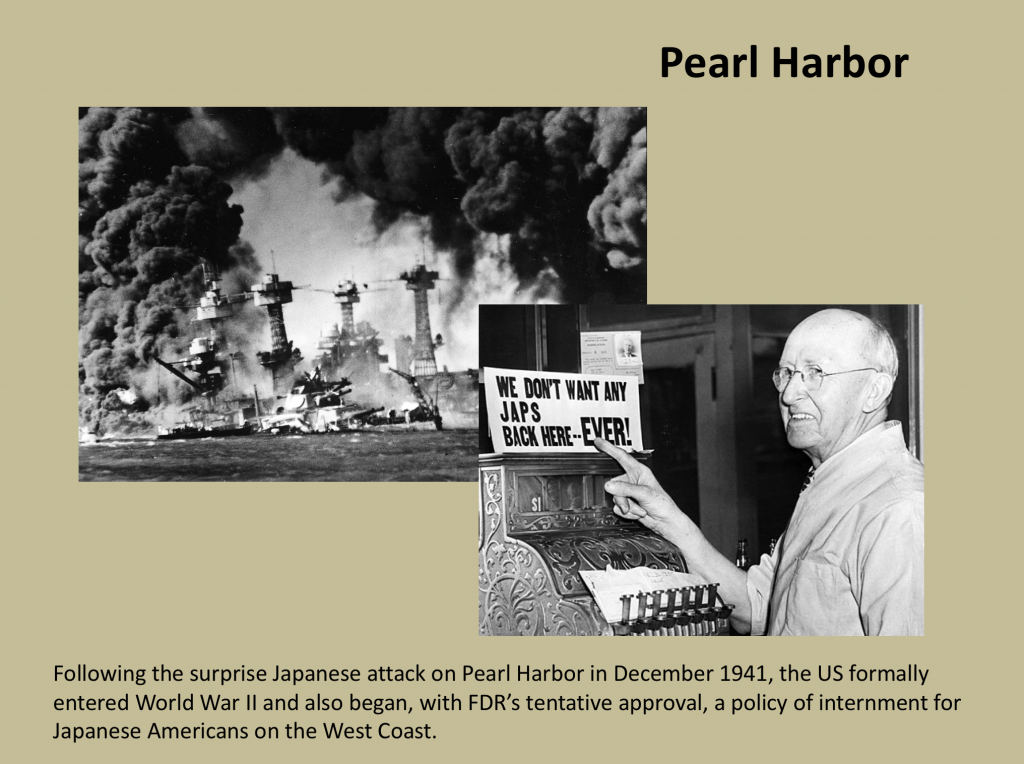

“The Japanese attack on Hawaii undermined as perhaps nothing else could have the cherished notion that America was secure from foreign threat. The ensuing war elevated foreign policy to the highest national priority for the first time since the early republic. By virtue of its size, its wealth, its largely untapped economic and military potential, and its distance from major war zones, the United States, along with Britain and the Soviet Union, assumed leadership of what came to be called the United Nations, a loose assemblage of some forty countries. During the war, it built a mammoth military establishment and funded a huge foreign aid program. It became involved in a host of complex and often intricately interconnected diplomatic, economic, political, and military problems across the world, requiring a sprawling foreign policy bureaucracy staffed by thousands of men and women engaged in all sorts of activities in places Americans could not previously have located on a map.”

“The Japanese attack on Hawaii undermined as perhaps nothing else could have the cherished notion that America was secure from foreign threat. The ensuing war elevated foreign policy to the highest national priority for the first time since the early republic. By virtue of its size, its wealth, its largely untapped economic and military potential, and its distance from major war zones, the United States, along with Britain and the Soviet Union, assumed leadership of what came to be called the United Nations, a loose assemblage of some forty countries. During the war, it built a mammoth military establishment and funded a huge foreign aid program. It became involved in a host of complex and often intricately interconnected diplomatic, economic, political, and military problems across the world, requiring a sprawling foreign policy bureaucracy staffed by thousands of men and women engaged in all sorts of activities in places Americans could not previously have located on a map.”

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 538.

- Executive Order 9066 (February 19, 1942)

- Korematsu v. US (1944) (Densho Encyclopedia)

- Ex parte Endo (1944) (Densho Encyclopedia)

- Esther Popel’s recollection of Mitsui (Endo) (1948)

View Solnit honor’s thesis website: What about India Now?

View Solnit honor’s thesis website: What about India Now?

FDR’s National Security “Organizational” Chart (selected figures)

- White House: Harry Hopkins, William Leahy, Eleanor Roosevelt

- Administration: Henry Stimson (War), Henry Morgenthau Jr. (Treasury), Jesse Jones (Commerce) Sumner Welles (State), Cordell Hull (State), Henry Wallace (VP), Bill Donovan ( OSS), Elmer Davis (OWI)

- Pentagon: George Marshall, Ernest King

- European Theater: Dwight Eisenhower, Virginia Hall

- Pacific Theater: Douglas MacArthur, Joseph Stilwell, Claire Chennault

- Western Hemisphere: [Hull + Welles] Nelson Rockefeller

- Asia / Mideast: William Philips, Alexander Kirk, Patrick Hurley

Media: Walter Lippmann, Henry Luce

Key Players, Witnesses, or Examples

- Wild Bill Donovan

- Walter Lippmann

- William Phillips

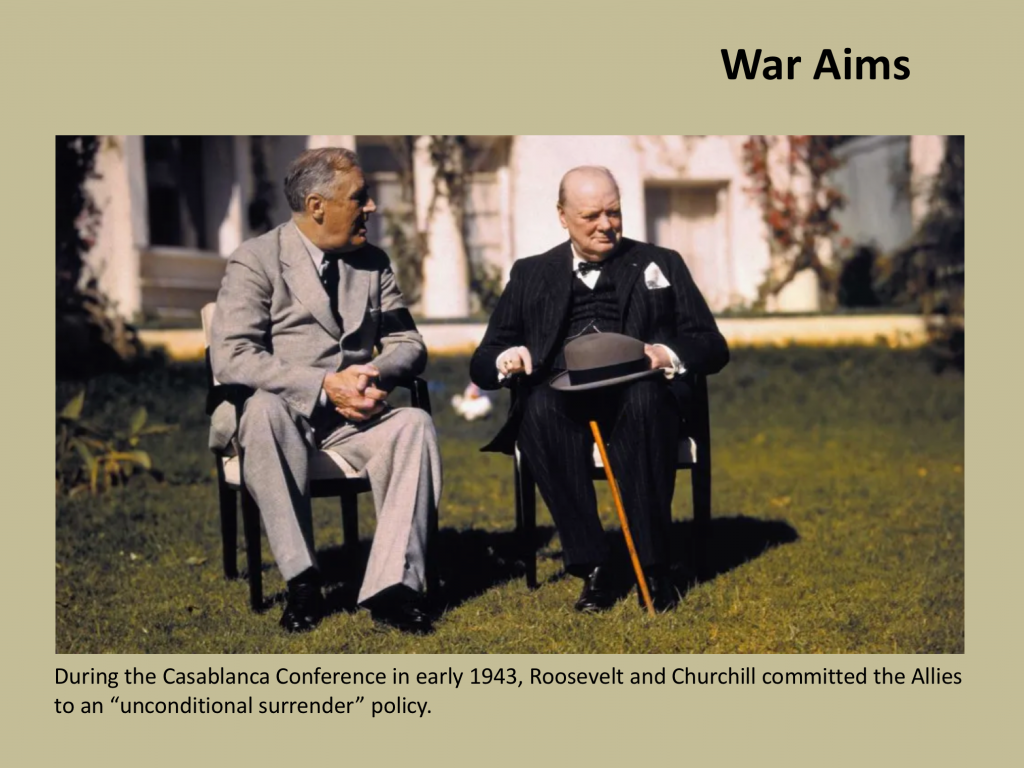

KEY TERMS: Casablanca Conference (1943) // Yalta Conference (1945)

Casablanca Conference (1943)

“As U.S. military planners had feared, the invasion of North Africa in November 1942 was followed by agreement at an Anglo-American summit in Casablanca in January 1943 to invade Sicily and then Italy. Since operations in North Africa and the Pacific were absorbing increasing volumes of supplies, the British now argued that the Allies lacked sufficient resources to mount a successful invasion of France and insisted that they follow up victories in the Mediterranean. Divided among themselves, U.S. military planners were no match for their British counterparts. ‘We came, we listened, and we were conquered,’ one officer bitterly complained. The harsh reality was that as long as the British resisted a cross-Channel attack and the United States lacked the means to do it alone, there was no other way to stay on the offensive. In any event, logistical limitations likely prevented a successful invasion of France prior to 1944. As a way of palliating Stalin’s Russia, the ‘ghost in the attic,’ at Casablanca, in Kimball’s apt words, Roosevelt and Churchill proclaimed that they would accept nothing less than the unconditional surrender of the Axis. The statement also reflected FDR’s determination to avoid repeating the mistakes of World War I, as well as his firm belief that Germany had been ‘Prussianized’ and needed a complete political makeover.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 552-53

Discussion Questions

- How to do you summarize the three-way dynamics of Allied strategic debates during World War II? What does Casablanca illustrate about the competing views of the Americans, British, and Soviets?

- Why was the call for “unconditional surrender” an attempt to avoid the “mistakes” of World War I?

Yalta Conference (1945) “Roosevelt discussed the issues with Churchill and Stalin for the last time at Yalta in the Crimea in early February 1945. The very name ‘Yalta’ has served as a metaphor for the ebb and flow of tensions with the Soviet Union. For some U.S. participants, the conference seemed, in Hopkin’s words, ‘the first great victory for the peace,’ a meeting where allies with divergent interests reached reasonable agreements to end the war and establish a basis for lasting peace. Less than ten years later, in the tense atmosphere of the early Cold War, Yalta became synonymous with treason, fiercely partisan critics of FDR claiming that a dying president, duped by pro-Communist advisers, conceded Soviet control over Poland and Eastern Europe and sold out Chiang Kai-shek. A ‘great betrayal,’ it was labeled, ‘appeasement greater than Munich.’ Because a ‘sick man went to Yalta’ and ‘gave away much of the world,’ Senator William Langer fumed, ‘our beloved country is facing ruin and destruction.'” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 584-85

“Roosevelt discussed the issues with Churchill and Stalin for the last time at Yalta in the Crimea in early February 1945. The very name ‘Yalta’ has served as a metaphor for the ebb and flow of tensions with the Soviet Union. For some U.S. participants, the conference seemed, in Hopkin’s words, ‘the first great victory for the peace,’ a meeting where allies with divergent interests reached reasonable agreements to end the war and establish a basis for lasting peace. Less than ten years later, in the tense atmosphere of the early Cold War, Yalta became synonymous with treason, fiercely partisan critics of FDR claiming that a dying president, duped by pro-Communist advisers, conceded Soviet control over Poland and Eastern Europe and sold out Chiang Kai-shek. A ‘great betrayal,’ it was labeled, ‘appeasement greater than Munich.’ Because a ‘sick man went to Yalta’ and ‘gave away much of the world,’ Senator William Langer fumed, ‘our beloved country is facing ruin and destruction.'” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 584-85

Post-War Multinational Structures

- Bretton Woods (1944): World Bank and IMF

- San Francisco (1945): United Nations Organization

Discussion Questions

- Herring goes on to write that the Yalta Conference in 1945 “cannot be understood” without appreciating its context. What was the most essential context for appreciating the challenges posed to FDR at this Big Three gathering?

- How should we assess the historic significance of the Allies in World War II? Did they win the war but lose the opportunity for shaping a better peace?

Dropping of the Atomic Bomb (1945)

Atomic Age

Col. Paul Tibbets was the pilot in command of the Enola Gay (a B-29 bomber named for his mother) that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945. The city had a population of about 350,000 at that time. The explosion immediately killed about 70,000 of those residents, destroying most of the city’s buildings. Tens of thousands more died in the weeks afterward. Tibbets was interviewed on camera, not long after he returned (August 19th).

Russell Baker was a young 19-year-old naval pilot originally from Virginia who was training to go overseas in the summer of 1945. He later became a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the New York Times who recalled his coming of age during the Great Depression and World War II in a famous memoir, Growing Up (1982).

“On August 9 the second atomic bomb was dropped at Nagasaki. Next night I wrote to my mother. “Well, today, to all intents and purposes, the war ended. The feeling of extreme elation which I had expected, existed for a bare moment, then life subsided back into its groove and it was just another day….” I didn’t confess that I hated the war’s ending. I knew she had been praying to God to save my skin; I could hardly tell her I was sorry her prayers had been answered… Still there was no hint in either my mother’s correspondence or mine that the arrival of the nuclear age interested us much. My mother, also excited about premature news that the war was over, had less cosmic things on her mind. The night after the Nagasaki bombing she wrote: “I’m still hoping that you’ll go to college when the war is over and study journalism; that is, if you’re still interested in that kind of work. Don’t lose hope and get married at this stage of the game.” (Russell Baker, Growing Up, p. 230)

John Lewis Gaddis of Yale University is one of the nation’s leading historians of the Cold War era. In this excerpt, he challenges the widely-held view that President Harry S Truman never hesitated and never questioned his decision to authorize the dropping of two atomic bombs on the Japanese in 1945.

“It took leadership to make this [containment of atomic war] happen, and the most important first steps came from the only individual so far ever to have ordered that nuclear weapons be used to kill people. Harry S Truman claimed, for the rest of his life, to have lost no sleep over his decision, but his behavior suggests otherwise. On the day the bomb was first tested in the New Mexico desert he wrote a note to himself speculating that ‘machines are ahead of morals by some centuries, and when morals catch up perhaps there’ll be no reason for any of it.’ A year later he placed his concerns in a broader context: ‘[T]he human animal and his emotions change not much from age to age. He must change now or he faces absolute and complete destruction and maybe the insect age or an atmosphereless planet will succeed him.’ ‘It is a terrible thing,’ he told a group of advisors in 1948, ‘to order the use of something that …is so terribly destructive, destructive beyond anything we have ever had …. So we have got to treat this differently from rifles and cannon and ordinary things like that.’” (John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War, p. 53)