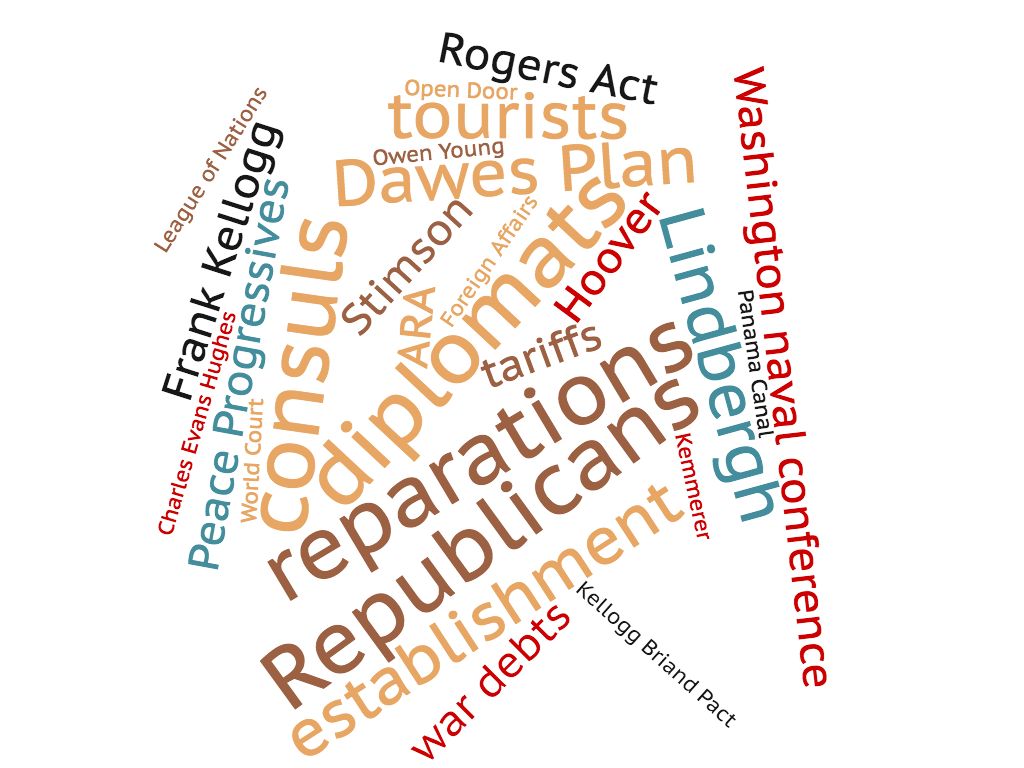

What was the main goal of US foreign policy in the 1920s?

CHAPTER 11: Involvement Without Commitment, 1921-1931

“Often dismissed as an isolationist backwater, the era of the 1920s in fact defies simple explanation. It lacks an overarching theme and a dominant Wilson-like figure. United States foreign policy derived from numerous complex and sometimes conflicting pressures, producing a bundle of seeming contradictions. The United States was without question the world’s top economic power, but it lacked commensurate military power and was not always inclined or able to use its economic might effectively. Republican officials went far beyond their predecessors in terms of involvement in world problems. The United States assumed a level of leadership quite unprecedented in its history. Still in the absence of a compelling external threat in light of Wilson’s recent experience, the Republican leaders did not defy the nation’s long-standing tradition against ‘entangling’ alliances and did not embrace collective security.” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 436)

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 436

KEY PLAYERS

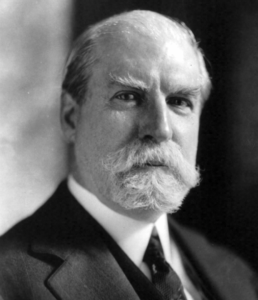

Charles Evans Hughes (1862-1948)

“During the 1920s, the secretaries of state resumed the preeminent role in policymaking they had played before McKinley and Roosevelt. The New York lawyer and unsuccessful presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes was one of the ablest ever to hold the post. An indefatigable worker, utterly devoted to the job, he filled the sizeable void left by Harding and Coolidge and was perhaps the last secretary to personally manage U.S. foreign policy. Hughes ably presided over a department with a budget of $2 million and a staff of six hundred people. He won the loyalty of his aides with his dedication and warm, outgoing personality. Blessed with a brilliant mind, he was also politically astute.” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 442)

“During the 1920s, the secretaries of state resumed the preeminent role in policymaking they had played before McKinley and Roosevelt. The New York lawyer and unsuccessful presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes was one of the ablest ever to hold the post. An indefatigable worker, utterly devoted to the job, he filled the sizeable void left by Harding and Coolidge and was perhaps the last secretary to personally manage U.S. foreign policy. Hughes ably presided over a department with a budget of $2 million and a staff of six hundred people. He won the loyalty of his aides with his dedication and warm, outgoing personality. Blessed with a brilliant mind, he was also politically astute.” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 442)

Charles Dawes (1865-1951)

“The administration named Chicago banker Charles G. Dawes and Owen D. Young, a General Electric executive with close ties to the J.P. Morgan banking firm, to head its group of experts, closely monitored their work, and stepped in on occasion to mediate disputes. It was no easy task. A settlement had to be hard enough on Germany to satisfy Allied and particularly French concerns while soft enough to be acceptable to Berlin. The fast-talking and indefatigable Dawes –an ‘astounding human dynamo,’ once colleague called him– also had close connections to France from his wartime service in Paris and helped bring the French along. Young devised a flexible and ingenious plan, ironically one that would bear Dawes’s name, that became a means not only to solve the intractable reparations problem but also to promote German recovery….Hoover exulted in the ‘disinterested statesmanship’ carried out by private American citizens and labeled the Dawes Plan a ‘peace mission without parallel in international history.’” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 459)

“The administration named Chicago banker Charles G. Dawes and Owen D. Young, a General Electric executive with close ties to the J.P. Morgan banking firm, to head its group of experts, closely monitored their work, and stepped in on occasion to mediate disputes. It was no easy task. A settlement had to be hard enough on Germany to satisfy Allied and particularly French concerns while soft enough to be acceptable to Berlin. The fast-talking and indefatigable Dawes –an ‘astounding human dynamo,’ once colleague called him– also had close connections to France from his wartime service in Paris and helped bring the French along. Young devised a flexible and ingenious plan, ironically one that would bear Dawes’s name, that became a means not only to solve the intractable reparations problem but also to promote German recovery….Hoover exulted in the ‘disinterested statesmanship’ carried out by private American citizens and labeled the Dawes Plan a ‘peace mission without parallel in international history.’” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 459)

KEY TERMS: Washington Naval Conference (1921)

“[Charles Evans] Hughes handled the [Washington naval] conference with consummate skill. He prepared with utmost care, mastering the technicalities of complex weapons systems without getting bogged down in detail. He kept U.S. naval officers on board without letting them take control. Avoiding Wilson’s mistakes, he made Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge part of the solution, thus preventing him from again becoming the problem. he developed a full-fledged plan for sizeable reductions in the tonnage of battleships, the ultimate weapon of the era, and kept his proposals secret until the conference opened. On November 11, 1921, Armistice Day, the delegates attended a moving ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery. The following day, in what journalist William Allen White called ‘the most intensely dramatic moment I have ever witnessed,’ Hughes unveiled his plan in what became known as his ‘bombshell speech’ before a stunned audience at Washington’s Constitution Hall. Addressing a packed house including prime ministers, admirals, the entire U.S. Congress, and some four hundred journalists from across the world, he insisted that the competition in armaments ‘must stop!’ He proceeded to call for the scrapping of sixty-six ships, including four British super-dreadnoughts authorized but not yet under construction and a Japanese battleship, the Mutsu, built in part with collections from schoolchildren. ‘Hughes sank in thirty-five minutes more ships than all of the admirals in the world have sunk in a cycle of centuries,’ an admiring journalist wrote.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 453-54

Discussion Questions

- If Secretary of State Hughes’s performance at the Washington Naval Conference of 1921 was so masterly and dramatic, why has this episode become so obscure?

- How does the story of naval disarmament on the Pacific during the 1920s illustrate what Herring calls the growing pattern of US “involvement without commitment” during the interwar period?

Dawes Plan (1924)

“The United States played a central role in resolving the tangle [over WWI debts and reparations]. The administration named Chicago banker Charles G. Dawes and Owen D. Young, a General Electric executive with close ties to the J.P. Morgan banking firm, to head its group of experts, closely monitored their work, and stepped in on occasion to mediate disputes. It was no easy task. A settlement had to be hard enough on Germany to satisfy Allied and particularly French concerns while soft enough to be acceptable to Berlin. The fast-talking and indefatigable Dawes –an ‘astounding human dynamo,’ one colleague called him– also had close connections to France from his wartime service in Paris and helped bring the French along. Young devised a flexible and ingenious plan, ironically one that would bear Dawes’s name, that became the means not only to solve the intractable reparations problem but also to promote German recovery. The plan scaled back the reparations figure and started with small payments that increased as the German economy improved. By requiring recipients to buy German products, it also helped kick-start German recovery. Germany was provided a loan of $200 million and required to undertake reforms U.S. businessmen considered essential. Responsibility for payment was assigned to an American, S. Parker Gilbert, who in the process gained substantial influence over German finances. Hoover exulted in the ‘disinterested statesmanship’ carried out by private American citizens and labeled the Dawes Plan a ‘peace mission without parallel in international history.’” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 459

Discussion Questions

- The US had rejected the Treaty of Versailles and remained out of the League of Nations. Yet the Dawes Plan of 1924 was one of only several ways that Americans remained invested in the post-war settlement in Europe and elsewhere. What were some of the key ways that US policymakers engaged with Europeans during the 1920s?

- The Dawes Plan helped illustrate rising US power in global trade and international economics. How did this newfound economic clout affect American priorities in foreign policy?