After a lifetime of enslavement, Paul Jenning’s achieved freedom in March of 1847 by Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts. Jennings had only had two masters prior, the most notable, and with whom he spent the most time, being James Madison; the fourth president of the United States.

Born on the Madison’s Montpelier estate in 1799, Paul Jennings was just a young boy when James Madison was elected president. In 1809 Jennings was moved with the Madisons to the executive mansion in Washington D.C., and had been chosen to be one of the footmen for the president. Jennings’ duties included setting for meal services, and greeting guests of President Madison.[1] Jennings describes Washington D.C. during the first years of the Madison presidency as “a dreary place,” with an unfinished presidential mansion, and and unpaved roads.[2] He lived with other members of the live-in staff at the cellar level of the building.[3]

Paul Jenning’s footman duties in the president’s mansion were fairly routine until war was declared in June of 1812. He notes in his narrative that before war was officially declared that President Madison would have constant meetings with Colonel James Monroe and other members of his inner circle, who Jennings points out, all were in favor of a declaration of war.[4]

When the British invaded Washington D.C. on August 24th, 1824 the British army began their assault on Washington, and Jennings, along with Madison’s and the live-in staff were forced to evacuate the capitol. Jennings had began to set up dinner that was to be ready by 3 o’clock, he recalls, when everyone in the mansion was ordered to clear out. It was in this frenzy, that the story of Dolley Madison saving the portrait of George Washington came about, but Jennings in his recollection debunks the story: “She had no time for doing it. It would have required a ladder to get it down. All she carried off was the silver in her reticule, as the British were thought to be but a few squares off, and were expected every moment. John Susé (a Frenchman, then door-keeper, and still living) and Magraw, the President’s gardener, took it down and sent it off on a wagon, with some large silver urns and such other valuables as could be hastily got hold of.”[5] Jenning’s recollection provides a key insight on what really happened during the British invasion and sheds more light on the decades old folktale. However, some historians and articles still do not recognize this.[6]

For the remainder of the war, Jennings, as well as other slaves of the Madisons, were moved to the home of Colonel John Taylor, who presided in Washington, until the end of the war.[7] He served as the Madison’s footman for the remainder of the presidency, and then was moved back to the Montpelier estate. There, he married another slave named Fanny and started a family. Fanny was from another plantation, however, so it is likely that the Madisons had to give permission to Jennings to marry across plantations.[8] It is also likely that this marriage was not seen as completely legitimate. Historian Peter Kolchin points out that marriages among slaves were allowed by owners to “promote ‘mortality,’ stability and a rapidly expanding slave population.”[9] It is clear that this marriage was not seen as legitimate, because Dolley Madison took Jennings with her to Washington after James’s death in 1836.[10]

Jennings spoke highly, and with great reverence of and for James Madison. In his reminiscences of the president he calls him “one of the best men that ever lived,”[11] and saying that Madison never hit a slave, or allowed an overseer to do so either. Slaves of the Madisons were reprimanded in private, as to avoid embarrassment for either the masters or the slaves, and were never punished with anything past verbal means.[12] Jennings was also at Madison’s side when the former president passed away, and had been acting as his personal caretaker for the final years of his life.[13]

After President Madison’s death, Dolley Madison took Jennings with her to Washington. Though they would still see each other, it is clear that Madison did not see Paul and Fanny’s marriage as legitimate. However, Dolley did make it a point to see that Jennings would be freed upon her death, according to her will. However, Dolley had to sell Montpelier in 1844, and only took Paul Jennings with her. Fanny, and the rest of Paul’s family was left at the estate, as they were sold as property. Fanny died shortly after.

Paul Jennings then returned to the White House under the Polk administration, doing similar duties as he did in the Madison administration, but this time working for pay, which he kept. In 1846, Madison sold Jennings to Pollard Webb. The following year, Webb sold Jennings to Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, who immediately freed him and hired him, in order for Jennings to pay Webster back the $120 he had spent for his freedom.[14]

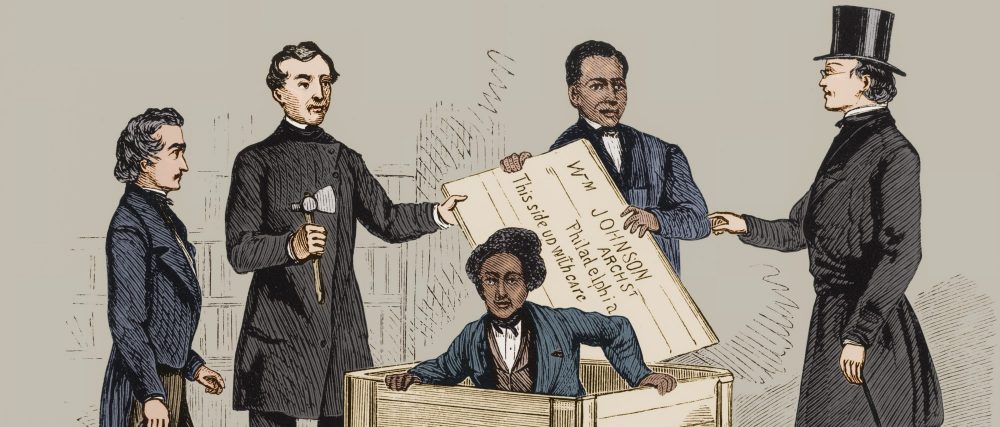

The remainder of Jenning’s life was spent as a free man. He was reconnected with his children from Montpelier, and remarried. He also took part in a movement to free upwards of seventy slaves in Washington in 1848. This movement was ultimately unsuccessful and was named the Pearl Incident, in which slaves from the surrounding area ran away at night and boarded the Philadelphia ship The Pearl. As soon as the morning came, these slaves’ owners found that their slaves had gone missing, and quickly pursued The Pearl, and took back their slaves.[15] Due to lack of evidence, it is unclear whether or not authorities found Jenning’s connection with this attempted escape.

Paul Jennings lived out the rest of his life in Washington, D.C., with his family close to him. He passed away in 1874. His life as a slave, and his journey to freedom is a common one of in-house slaves among wealthier families, however Jennings had the luxury of living in the White House for many years, during, and well after the Madison presidency, and even received payment during the Polk presidency. He achieved freedom at the hands of a Massachusetts senator, and lived out the rest of his days in Washington, D.C. as an abolitionist with his family.

[1] Samuel Momod,. Jennings, Paul (1799-1874) in Black Past. 2012. [Black Past]

[2] Paul Jennings. A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison. (Brooklyn. 1865). 6.

[3] Elizabeth Dowling Taylor. A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons. (New York. 2013). [Google Books]

[4] Jennings. 6.

[5] Jennings. 13.

[6] See Jeff Broadwater. James Madison: A Son of Virginia and A Founder of a Nation. (University of North Carolina Press. 2012.). And Taylor. A Slave in the White House.

[7] Jennings. 11.

[8] Momodu. Jennings, Paul.

[9] Peter Kolchin. American Slavery: 1619-1877. (New York: Hill and Wang. 1993). 123.

[10] Momodu. Jennings, Paul.

[11] Jennings. 15.

[12] Jeff Broadwater. James Madison: A Son of Virginia and A Founder of a Nation. (University of North Carolina Press. 2012). 189. [JSTOR]

[13] Jennings. 18.

[14] Momodu. Jennings, Paul.

[15] Samuel Momodu. The Pearl Incident in Black Past. [Black Past]