- Video clip: Douglass & North Star [PBS]

- Video clip: Douglass & pacifism [PBS]

- Brief profile (by David Blight) with links to published autobiographies (1845, 1855, 1881/92) [DOC SOUTH]

- Research engine records [HOUSE DIVIDED]

The power of first-hand accounts

“Many slave owners came to take greater interest in the lives (and general welfare) of American-born slaves –with whom they had sometimes grown up –than in those of newly purchased Africans who appeared strange and ‘savage.’ More important still, the growing number of blacks in America, the increased size of holdings, and the more equal sex ratios provided greater opportunities for finding spouses than had previously existed. During the half century before the War for Independence, second- and third-generation American slaves built a new system of family relations to replace that shattered by the slave trade; basic family patterns that would persist through the antebellum period became established, patterns that resembled in broad outline those found among white Americans but that differed from them in important specifics.” –Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, p. 50

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Cultural Sources

Slave Life at Mount Vernon (Fairfax Co Public Schools)

“Roots” (1977)

This research guide offers digital tools for teachers and students to explore the history of slavery and abolition in Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania County Slave Records

Pennsylvania Laws and Court Cases

Slavery and Northern Colleges

Letters and Diaries

Speeches and Anti-Slavery Conventions

This week, I sought to tie up some loose ends my previous research left. I began by going through Spahr’s chapter on Noah Pinkney and finding images of objects and pictures that were described to humanize Pinkney.

In this chapter, Spahr claims that in Pinkney’s house “on the wall behind [one of the rooms] are some shelves containing a few jars of peppermint stick slowly crumbling to decay, flanked by an unframed print of Lincoln freeing the

Image of Lincoln freeing a slave. This is the print that most likely hung in Pinkney’s house. Courtesy of Wise Guide: On Texas Time in June 2011 from the Library of Congress.

slave and a certificate of membership in the colored Odd Fellows, both somewhat the worse from fly-wear.” (Spahr 56) There were The print of Lincoln freeing a slave was most likely the image “Emancipation of the Slaves” in which Lincoln stands over a hunched black man and shakes his hand. I decided it is most likely this image because it is the only one in which Lincoln is seemingly freeing a single slave. The other image on Pinkney’s wall as described in this recollection is the certificate from the colored Odd Fellows. While I was unable to find his certificate, I found one for David Bustill Bowser, one of the more prominent members of the colored organization entitled the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America (G.U.O. of O.F). In addition, I found a picture from circa 1890-1930 of members of the G.U.O. of O.F. by searching for the “colored Odd Fellows.”

Image of David Bowser’s certificate of membership into the G.U.O. of O.F. dated 1843. Pinkney most likely had a membership certificate similar to this. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collections in the Library Company of Philadelphia.

In addition, in the description of Pinkney, Spahr said that he wore “an old slouch hat on his head” (Spahr 56). In many of the pictures of Pinkney, he is wearing this type of hat.

Image of Noah Pinkney wearing old slouch hat. Courtesy of the Noah Pinkney image file in the Dickinson College Archives.

Image of an old slouch hat. Courtesy of the Historical Emporium.

In addition to searching through Spahr’s recollections, I also, with the help of Professor Pinsker and archivist Jim Gerencser searched through treasury records that would be uncover wages paid to black janitors.

The ledger from 1882 lists “H. Spradley” and “R. Young” as being paid wages for June 1882 and for matches.

Ledger from 1882. Courtesy of treasurer records from the Dickinson College Archives.

In May 1873, there were three checks made out to janitors. The three janitors were Sam Watts, Robert Young, and George Norris. It appears as though Norris was unable to write because the back of his check has a shaky cross drawn on it, which was a way for illiterate people to sign documents.

Checks for janitors of the college. Courtesy of the treasurer records from the Dickinson College Archives.

Signed backs of checks for janitors. Courtesy of the treasurer records from the Dickinson College Archives.

The final document is made up of a few payment vouchers from 1857 for some of the janitors. Two are made out to Sam Watts and two are for Henry Watts.

Payment vouchers for janitors. Courtesy of the treasurer records of the Dickinson College Archives.

By searching through treasury documents and looking for images described in the Spahr memoir, I have been clearing up inconsistencies and finding more information in places where my research thus far has been lacking.

This week, I planned to focus on understanding more on Jim Powell and Sam Watts because I did not have much information on them.

I began by going to the Dickinson College Archives to inquire about treasurer files relating to employees. They were unable to find treasurer files from the 19th century, so they gave me faculty minutes instead. Unfortunately, but predictably, there was nothing in the faculty minutes that was even semi-related. I also asked if there were any files relating to Powell, Watts, or custodians in general beside the sources already in the drop file. This search also led to a dead end. Because I remembered seeing the “Corps of Hygiene” that provided information and pictures of the black custodians from the 1870s in a copy of the Microcosm, I decided to leaf through a few of the earlier Microcosm’s that have not yet been digitized. While I could not find anything similar to the “Corps of Hygiene,” I did find an interesting page relating to the

Faculty page that lists Spradley and Young as professors in the 1882 Microcosm. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

janitors in an 1882 Microcosm. Listed on the second page of the “Faculty” section, are “Henry Spradley, J. A. N., Adjunct Professor of Experimental Physics,” “Rev. Robert Young, A. M. E. C., Adjunct Professor in Dutch Scientific Course,” and their “Assistants” in West College (Shirley, Kurnel, and John) and East College (Bud, Bob, and Charlie). This most likely satirical piece may reveal six additional black janitors (the three from East College and the three from West College) to further research.

Drawing of “the Janitor” found in the 1881 Minutal. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

Next, I went to the Cumberland County Historical Archives to search through Newspapers.com for references to Powell and Watts. Based on previous research and information from Professor Pinsker, I searched “Banty Jim,” “Jim Powell,” “James Powell,” “Pompey Jim,” “Sam Watts,” and Samuel Watts.” Using Watts’s search names, I only found a handful of articles that related to him. I also only found one article on Powell that I had not seen before. I then tried searching “Dickinson custodian(s),” “Dickinson janitor(s),” and “Dickinson employee(s).” Each of these searches came back with no results. Newspapers.com does not allow advanced searches, so I could not search for “Dickinson” and “custodian,” which may have yielded some results.

I finished my research for the week at the Dickinson College Archives. I asked for information regarding either Watts or Powell and received a bound thesis written by John Alosi called Shadow of Freedom: Slavery in Post-Revolutionary Cumberland County, 1780-1810. The front cover has a picture

Cover of Alosi’s thesis featuring image of Powell. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

of Jim Powell, and a brief background of him appears in “On the Cover,” a page-long chapter that appears at the beginning of the thesis. The information in this chapter comes from the 1840 census. I also looked for references to slaves, former slaves, and slavery in the card catalogue, and with the help of an archivist, found a few letters by and to various members of the

Page about Powell from Alosi’s thesis. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

Dickinson community regarding their position on slavery from Antebellum to Reconstruction Era. These letters, mostly concerning Dickinson presidents, should be able to provide a basic background on Dickinson’s ties to anti-slavery and pro-slavery, which will be helpful for my Dickinson and Carlisle background page. Finally, I searched through the presidents’ files and pulled documents that seemed like they might be related to black janitors/employees

Letter insisting on the firing of the janitor. Courtesy of the Dickinson College Archives.

at Dickinson. Here, I found a few letters that will also help to give background to Dickinson’s ties to slavery (particularly relating to the McClintock Riot). However, I found a letter from President W. Neill to the Dickinson College Trustees on September 28, 1826 to insist upon the removal of the janitor because he “has become so very negligent of his duty.” This letter may provide insight into when former slaves or free black men began serving as janitor at the college. It also may prove that the employment of black janitors began at least 16 years before the 1842 letter regarding the employment of former slaves was written to Robert Emory.

While I did not find much more on Powell and Watts than I already had, I found a few interesting sources to humanize them, a few more potential names to add to the list of black janitors at Dickinson College, and background information on Dickinson’s complicated relationship with slavery.

Expanding off a previous research journal post, I continued searching the Dickinson College archives for references to slave labor in the construction of the first two college buildings. The Board of Trustees Papers (RG 1/1) are where Georgetown University’s Cory Young first discovered a mention of “Black James, Mr. Holmes’ Negro” who was paid 15 shillings for work on the college on July 26, 1799.

I first wanted to follow up on John Holmes, who as a slave owner was more likely to generate records than the bondsman James. To do so, I used the record group’s finding aid, available online. There, each series within the group is broken down into boxes and then folders, with brief descriptions of their contents. Looking through the finding aid for Series 6, (the Financial Affairs records) I found a folder labeled “Bill of John Holmes for expenses incurred while collecting subscriptions in Baltimore.” True to the description, the folder contained a bill submitted on April 16, 1799, listing Holmes’ expenses on a trip collecting subscriptions to fund the new college’s construction. The first slip showed Holmes’ request to be reimbursed for “2 Horses” and “36 Gallons of Oats,” but on the second slip the otherwise mundane document assumed a new light. Tallying the expenses, Holmes also sought reimbursement “for Jem and two horses for Sixteen Days,” almost certainly the same “Black James” who would appear again, just three months later, in the financial ledger already discovered by Cory Young. [1]

John Holmes’ bill for expenses, April 16, 1799. (Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections)

Holmes asks to be reimbursed for “Jem and two horses for Sixteen Days” (Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections)

This record suggests that James, the slave of John Holmes, accompanied his master to Baltimore, and that Holmes billed the college for James’s time. It is an indication that enslaved people were hired out to Dickinson College not just within the limits of Carlisle, but also in the course of larger fundraising efforts. [2]

These records, from 1799, pertain to New College, the initial college building constructed between 1798-1803. As it neared completion, however, the structure burned in early 1803, and a new fundraising campaign was launched to build what is today know as West College, or Old West. I sought to broaden the scope of my research by looking into contracts arranged for the building of West College, and see if any enslaved labor was used in its construction.

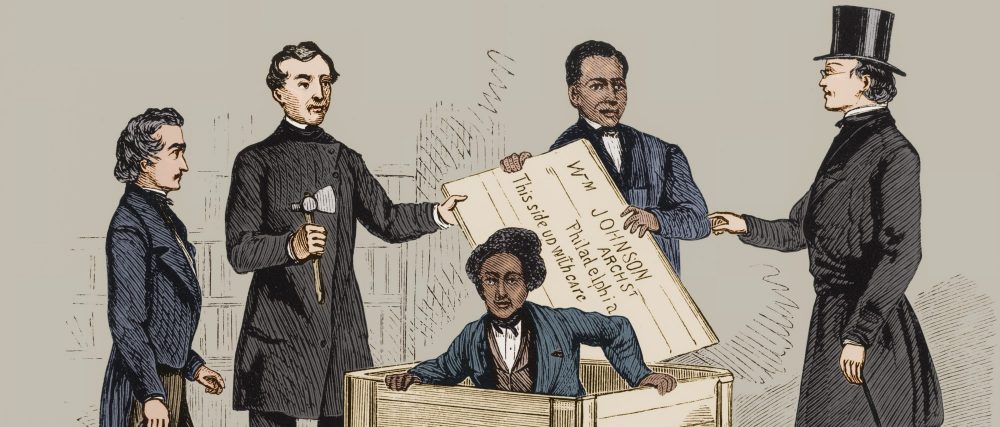

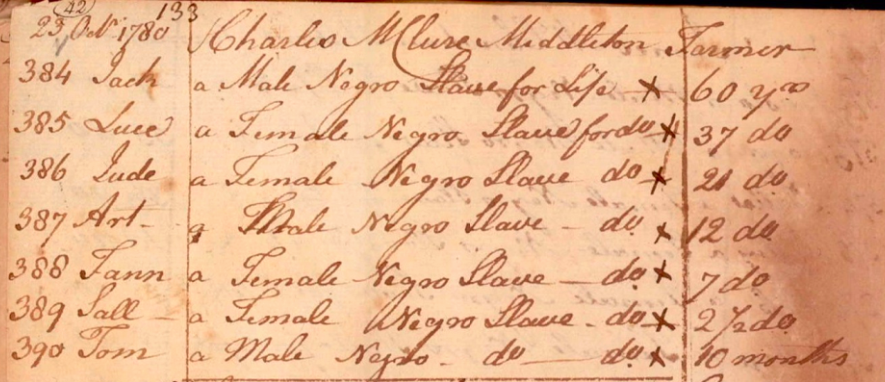

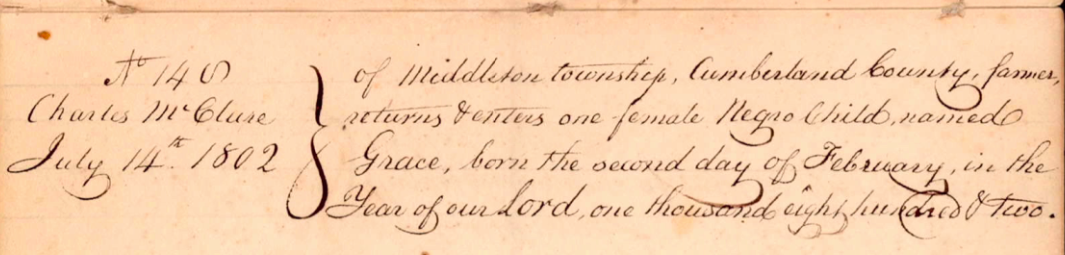

Using the same finding aid, I noticed a file named “Contracts for goods and services, including a partial list of contractors.” Inside was a handwritten list of contractors whom the college had hired, as well as the material they were to supply. I referenced the names against those of slave owners appearing in the Cumberland County Slave Returns to see which of the suppliers owned slaves. While at least three of the contractors had registered slaves in 1780, it proved more difficult to verify whether or not they still owned slaves some 23 years later. There was one exception: Charles McClure, a farmer from neighboring Middleton township, who had served as a Trustee of the college since 1794. McClure, who had agreed to deliver 3,000 bushels of sand for the building of West College, had previously registered seven slaves in 1780, and more recently the birth of a “Negro Child named Grace” in 1802. [3]

Charles McClure registers 7 slaves in October 1780. (Cumberland County Archives)

Charles McClure registers another slave birth in 1802, shortly before he was contracted to work on Old West. (Cumberland County Archives)

While McClure’s slave registrations are far from definitive proof that enslaved labor was used to deliver materials for the building of West College, it does show that the college hired a local slaveholder to supply materials. What remains to be seen is if any more definitive connections between the construction of Old West and slave labor can be made.

Notes

[1] Bill of John Holmes, April 16, 1799, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 6.4.33, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections.

[2] As noted in my previous post, a man named William Holmes registered a “Negroe boy named Jim” in October 1780. Georgetown University’s Cory Young has found that William Holmes died within several years of registering “Jim,” sometime prior to August 1785. (See Estate Advertisement, Carlisle Gazette, August 17, 1785, Readex Early American Newspapers Database). It is possible that “Jim” went from William Holmes to his brother, John Holmes. Regardless, what remains clear is that by 1799, John Holmes owned an enslaved man of working age known alternatively as “James” or “Jem.”

[3] Contracts for Goods and Services, West College 1803, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 5.4.4, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Carla Christiansen, “Samuel Postlethwaite: Trader, Patriot, Gentleman of Early Carlisle,” Cumberland County History, 31 (2014): 34.

After discovering information on Sam Watts in the Dickinson janitorial drop file, I began to wonder if Samuel Water was a misspelling of Samuel Watts. Professor Pinsker and Dickinson College Archivist Jim Gerencser confirmed my suspicions. I returned to Ancestry.com and researched for “Samuel Watts.” The search yielded nine results for multiple people named Samuel Watts. Knowing he worked at Dickinson in the 1870s, I disregarded all entries that marked the birth year after 1870. Because all the other people called Samuel Watts were born after 1880, I was left with two sources that applied to the correct Samuel Watts. The first is the 1860 census and the second is the 1870 census.

According to the 1860 census, Sam Watts was born in Virginia in about 1836. This implies he would have been a slave during his childhood. By 1860, he had moved to Carlisle and worked as a waiter. He was married to Martha Watts who was a 22 Pennsylvanian born washerwoman. Their children were Agnes (7), Laura (3), and Cecilia (3 months).

This is the 1860 census of Samuel Watts in Carlisle, PA. Courtesy of Ancestry.com.

According to the 1870 census, Sam Watts was born in Maryland in about 1832. This would still imply he was a slave for his life but makes him about four years older. By 1870, he was employed as a college janitor. He was still married to Martha Watts, but she is listed as only 26 years old by the 1870 census when she should have been about 32 based on the 1860 census. Their children were Agnes (14), Laura (12), Henry (8), and Nelson (3).

This is the 1870 census of Samuel Watts in Carlisle, PA. Courtesy of Ancestry.com.

While I do not know which census is correct (if either) regarding Sam Watts’s birth year or birthplace or Martha’s birth year, it is very likely that Sam Watts was previously a slave. Both Virginia and Maryland likely would have enslaved him. A slavery status might also explain why his birth year is uncertain by a span of four full years. The census records also reveal that he became a janitor at Dickinson sometime between 1860 and 1870.

In order to properly explain the relationship between slavery and the founding of Dickinson, I needed to provide context about slavery in Cumberland County during the college’s formative years. To do so, I turned to the Early American Newspapers database (Readex), made available via the Waidner Spahr library. Using the advanced search option, I entered “Negro” in on of the search bars (“Negro” is often used in place of “slave” in runaway advertisements) and set the place of publication as Carlisle. Most of the ensuing results were from the Carlisle Gazette, a paper established around 1785 that served as the town’s main organ during the period of Dickinson College’s founding.

Immediately, I found a record that tied Dickinson College even closer to slavery. It was a June 1787 notice placed by Trustee John Montgomery, one of the key figures in the college’s founding. He sought to sell a “strong, healthy Negro Wench, and a female Child six months old,” along with “two negro Boys, one about six and the other about four years old.” [1] Prospective buyers would have paid close attention to the ages of the enslaved children, knowing that those born after March 1, 1780, would eventually gain their freedom when they turned 28. Still, until then, the three children Montgomery had put up for sale could be sold legally within state lines and treated in the same way as those who were slaves for life.

Dickinson Trustee John Montgomery advertises four enslaved people for sale. (Carlisle Gazette, July 25, 1787, Readex Early American Newspapers Database)

Pennsylvania’s 1780 Gradual Abolition law, and the oftentimes muddied status of bondsmen in places like Cumberland County, led to considerable confusion. In late 1796, a man named James was arrested “on suspicion of being a Runaway” and housed in the Carlisle jail. “The negro says that he was not recorded,” read the notice, an indication that local African-Americans were using the Gradual Abolition law and its strict requirements on registration to their advantage. [2]

Beyond glimpses into local slavery, I had also hoped to find reference to the school for enslaved children founded around 1788, which I wrote about in a previous post. The school was intended to offer a Christian education for the children of “those people laboring under the unfortunate condition of slavery” in Carlisle and the surrounding region. [3] Remembering that one of the pledges on the school’s founding document, held in the Dickinson College Archives, came from the firm Kline and Reynolds (the printers of the Gazette), I speculated that they may have mentioned the school in their paper.

Modifying the search terms to “School,” with the place set as Carlisle and specifying the year as 1788, I found a specific mention to the school, which the editors of the Gazette referred to as the Charity School. It described a meeting of the subscribers, in which “it was agreed to set aside that part of the original plan, which respects the negroes.” This decision may reflect the second document contained in the Dickinson archives, where the school was shifted from a weekday school to an exclusively Sunday evening school, evidently geared more towards the poor white children than those of slaves. “It is hoped that many parents, unable to educate their children themselves,” read the notice in the Gazette, “will embrace this opportunity of obtaining the aid of the benevolent.” [4]

Notice of the founding of the Charity School. (Carlisle Gazette, November 28, 1787, Readex Early American Newspapers Database)

Now armed with a name, I added the term “Charity” to “School,” and removed the date restriction. With these new terms, I found what I had originally sought—a notice of the school’s founding. The Charity School began in November 1787, “intended for the purpose of instructing poor persons in reading, who are engaged during the week in the business of their employers or masters,” and was held initially on Sunday evenings at the Court House. During its inaugural session, 23 “scholars” were addressed by Dickinson College president Dr. Charles Nisbet, who encouraged them to “acquire a knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, imbue the precepts of the Savior of mankind, and converse as it were with his Holy Apostles[.]” [5] Using the same terms, I found yet another allusion to the Charity School in January 1789, announcing that the “subscribers” (those who had pledged money to sustain it) were to meet at Dickinson College, tying Dickinson even closer to the school. [6] What remains to be discerned is why the school’s subscribers (many of whom were Dickinson Trustees) decided to “set aside that part of the original plan, which respects the negroes,” and what that can tell us about the complicated relationship Dickinson’s founders had to slavery.

Notes