A Documentary Discussion

May 26, 2016

Over the past few days, my group and I have visited the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant and have interviewed a number of people varying from professors alive at the time of the incident to leaders of nuclear watchdog groups. These experiences allowed me to have a greater insight into the way people of the United States interact with nuclear disaster. We made sure to ask basic questions inquiring about where they were at the time of the incident as well as more thought-provoking ones about their positions on having a nuclear power plant right in Central Pennsylvania’s backyard. We made sure to keep these interviews private in order to conceal their identities. I will go further into detail about my interview experience when we do our first interview in New Jersey or Japan as I would like to compare/ contrast my experiences across cultural borders (even within the U.S.).

What struck me the most throughout these past few days have been the number, or lack thereof, of minority stories and/or representation in both the nuclear industry as well as the introductory videos our class had today about The Tōhoku earthquake, tsunami, and resulting nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant. Specifically, in a NOVA special our class watched today on Tōhoku, all of the scientists and journalists were, well, western males that were from either the United States or other western countries such as Great Britian. This does not bother me too much on a usual basis as access to scientific information is often only accessible to those that have the income or social privilige to do so. However, the documentary was made in order to inform the public about a natural disaster that killed over 15,000 Japanese individuals, and yet, none of the scientists, journalists, or spokespeople were of Japanese origin. Even more so, there was only one interview of an elderly Japanese farmer couple that lived significantly farther away from the disaster than other potential interview candidates. Yes, there exists certain limitations that may not be controllable towards choosing interviewees for an American documentary. For instance, Japan and the United States have not necessarily had the best past in terms of diplomatic relations and other politics, and individuals may have been sensitive towards being interviewed after such a devastating series of events, but I am sure there existed at least a single voice that was willing to reach out and share their story. In addition to this, many filmographic techniques were used to make the documentary dramatic and entertaining such as camera angles and music choice.

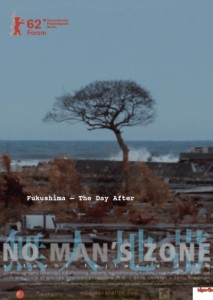

Luckily, the next documentary we watched was entitled, “No Man’s Zone,” which is a documentary done by and for the Japanese people.

This documentary was very raw, and the female narrator incorporated comments that helped the viewer understand the situation at hand. For instance, she mentioned in the beginning of the film that it was difficult for a cameraman to film in a certain area because of the emotional burden attached to stepping on fresh rubble and potentially, a human body. The narrator also incorporated many philosophical comments on the nature of humans. For example, she critiqued society as she stated that people sometimes tend to leave devastating images out of the discussion of the aftermath of disasters because of an innate fear humans have of death. The documentary also consisted of dozens of interviews of Japanese people, both anonymous and not.

Some may see the tactics used in this film as “dramatic,” but I would like to challenge that thought. Is it dramatic because it surpasses the westernized perceptions and expectations we have of documentation, especially concerning natural disasters? Is it dramatic because a woman is the narrator and not a man? Was it dramatic because the images were raw and of rural areas that would not normally have been displayed and represented?

This series of examinations I’ve had can quite literally go on forever, so I would like to conclude on that thought. Perhaps this documentary was not entirely scientific, but it did provide me with an additional lens that I longed for when learning about the Tōhoku region and the Fukushima disaster. Maybe the supreme form of a documentary will contain both diverse narratives and raw imagery as well as information on the scientific processes that occurred during the event, and maybe a clash between the two will never allow us to reach that point.

Leave a Reply