Back to the Atlantic

June 14, 2016

Our last day in Japan consisted of a lot of travelling, and during this time, I was able to reflect a lot on the experience I’ve had in this class thus far. Spending my last 500¥ was a very intimate moment between myself and the cashier at Muji, a very high end, minimalistic store in Japan. With 500¥, I was able to buy an eraser, which better be the most flawless eraser of all time.

My eraser from Muji and some mochi for snacking

My eraser from Muji and some mochi for snacking

Also, I cannot help but mention that on our last morning in Japan, I experienced a 4.9 earthquake, and got completely excited. I know that this reaction is probably not the best to have during an earthquake, but knowing how small its magnitude was and how seismically safe the buildings in Tokyo are, I think my feelings at the time were pretty validated. Growing up in California, I have always been fascinated with earthquakes and plate tectonics in general. Experiencing an earthquake in one of the most seismically active zones on the planet DEFINITELY had me jumping up and down (mentally and quite physically). Not to mention, when I got the notification from one of the many seismic apps on my phone, tears welled in my eyes– a girl’s dream has finally come true.

I had to screenshot the overlap of my location and the location of the quake so I could look back on the wonderful moment in years to come.

I had to screenshot the overlap of my location and the location of the quake so I could look back on the wonderful moment in years to come.

On the half-day flight, I managed to write some more poetry and such on my experiences in New Jersey and Japan, specifically pertaining to natural disasters (while Three-Mile Island was not necessarily a natural disaster). Through this, I found that many of the people we interviewed were women. Being the only woman in this group, this was not really noticeable to me until one of my colleagues pointed it out, which was quite interesting since I usually notice these patterns when analyzing another person’s research. The women were also mainly mothers that were concerned with the situations at hand. In a previous blog, I mentioned that many families were split up because the concern mothers had did not match up with those of fathers. Similar situations occurred in New Jersey (referring to the mother that left when the evacuation notice was given and the father that stayed), which I did not expect to find in the Japanese response to disaster.

Ultimately, I have realized that the most damage from all of the disasters we have studied have been social and emotional. Since it is too early to tell whether the Fukushima explosions caused radiation-related diseases and the casualties of Sandy and Tohoku have very finite numbers, the amount of families and communities that were and still are affected by these events surpasses the numbers. As a result, economies and local governments are seen as criminal and many communities, both in the United States and Japan. In the future, governments must recognize the potential ethical dilemmas that may rise from ignoring certain populations of people.

View of Tokyo from the 350th floor of the Skytree

View of Tokyo from the 350th floor of the Skytree

Tōhoku

June 12, 2016

North-eastern Japan was very different from Tokyo. From the larger roads to the mountainous terrain, the Tōhoku region gave me another reason to fall in love with this country.

Our experience up north was mainly divided into two sections of study: nuclear disaster and natural disaster. In Fukushima prefecture, we interviewed many individuals that were directly affected by the Dai-Ichi explosion in March of 2011. Many of these people were moved into temporary housing because of the earthquake’s damage and/or dangerous radiation levels in their communities. The other majority of people we interviewed were concerned mothers that changed their family’s lifestyle to accommodate for a safe environment for their children. Because of this, many families were split up by their mother’s precautions and their father’s disagreement with the extremities of these safety precautions. For instance, some mothers decided to keep their children indoors and not allow them to play outside and others moved from dangerous cities entirely, leaving their husbands behind to work. Many couples did not agree on the potential for danger with high levels of radiation in the atmosphere, and continue on living separately. Because of this, many mothers we interviewed were afraid to communicate their fears of radiation poisoning and danger in their area with the larger public, resulting in small groups of mothers spread across the Fukushima prefecture. Many mothers met without their husbands knowing simply to avoid conflict.

As we trekked further north, we saw the earthquake and tsunami damage closer to the epicenter of the 3.11 disaster. This was one of the hardest parts of the trip. We visited the Ogawa Elementary school where almost all of the people on the roof of the school went missing or passed away as a result of the tsunami’s height. Some escaped to higher grounds, but others did not. This experience really emphasized the intensity of the tsunami and how large the surge was because even though these people were prepared for disaster to strike, they could not have been prepared for 3.11. Seeing the elementary school and other devastated areas like the Disaster Response Center in Minamisanriku where many deaths happened as well made me wonder whether disaster preparedness is really possible. Yes, there are basic things everyone must know to do such as store food and water and extra clothes, but the intensity of disasters cannot be predicted as much as we want to believe they can. The term “disaster preparedness” is actually contradictory in itself. Must we redefine disaster preparedness? Can we even be really prepared for disasters like the “big ones” scientists talk about all the time?

A view from Fukuurajima

The disaster response building in Minamisanriku and a community-built memorial

A mural remaining from the elementary school

Push

June 10, 2016

The past week has been filled with narratives that I am not sure how to share in words other than a poem.

You are not who I expected you to be.

Pulling back before releasing you

are not who they expected you to be.

whole homes stripped to

foundation homes

thought to have had

foundation

Homes no longer a home but toothpicks for you to pick grime out your teeth, consuming

reminding us that we consume without asking

And you came without asking

You are proof that you act on your own, a

vessel we are only guests on

clipping phone lines like floss string and plucking bolts off tracks, flicking them to destination

Concrete walls like Lego pieces, your job to disassemble.

You are reclaimation of space and decolonization in its purest state.

You are time-machine, begging.

and you push. you push

cousins into alcoholism push yourself onto shores familiar with your frequent kisses but not your abuse and you push.

Only now must we realize that you push.

You are not who I expected you to be,

Storm without calm

always

pushing

The inundation zone in Minamisanriku, a part of the Tōhoku region in Japan severely hit by the tsunami on March 11, 2011

A radiation level posting in Fukushima-shi

An abandoned building with earthquake damage in Tomioka, a city evacuated due to high radiation levels

Sharing a Sea

June 3, 2016

The past week has been such a blast. I flew in to Tokyo on Tuesday around 3:30 PM local time, leaving from the East Coast on Monday. I still am not sure whether it was the 12-hour flight or the fact that I finally landed in a place I have always wanted to visit, I felt something…different. Nonetheless, we were immediately immersed into our Japan-phase of our projects that day.

Specifically, I am conducting research on how Japan and the United States deal with natural disasters and their aftermath and whether the two are significantly different. To better our understanding of Japan’s experience with disasters, I did a variety of things with my group such as visit the Edo-Tokyo Museum, the Tokyo Center for Disaster Preparedness, the Peace Boat (NGO) headquarters, and attend an anti-nuclear power protest. Of all of my experiences here, the most refreshing thing to do was meet with undergraduate students that attend Chuo University in Tokyo. We asked them a coupls of questions about their memories of the Tōhoku quake/ tsunami, and many of them were doing daily things in junior high school when they felt the P-waves from the earthquake’s epicenter. Tokyo is quite far away from the Tōhoku region in terms of Japan’s size, and the students still felt the earthquake in a major city. This concerned me a lot as I recently learned that Tokyo is predicted (70%) to have a major earthquake in the next 30 years, which highly likely to be in the range of our lifetime. These students were second and third-year students who are close in age with me, making the situation a lot harder to swallow. Even more so, I asked them all if they were ready to experience something like this, and only 1/4 students in my group had a legitimate, tangible disaster kit with essentials packed away in it for him and his family. After finding this out, the group and I laughed as we realised this student was the only one who had their life together. The students have all experienced natural disasters, but there is always the possibility of so ething bigger and unpredictable to occur at any time along Japan’s rapidly changing faults and plate boundaries.

This made me think a lot about disaster preparedness and mitigation. Is there a point where preparedness reaches an extreme? How will we know the difference between living in fear and being prepared at any moment? Can we really be prepared at any moment?

We carried on our conversations to dinner at a traditional Japanese restaurant. There, I learned more about the culture directly from the students and the customs of Japanese dining.

Below are a couple of more things we did throughout the city:

We visited shops around the Tsukiji Fish Market.

This is the helipad and evacuation zone at the Tokyo Disaster Center.

(various views of the city)

(an interesting makeshift loo in the case of an emergency happening while in an office or on a campus)

(an interesting makeshift loo in the case of an emergency happening while in an office or on a campus)

I am glad to say I have finally bridged the gap I longed for across the Pacific, and have created a new relationship with myself and the ocean I have always called home.

Jersey Shore and More

June 2, 2016

Last weekend, our group spent time in Toms River, New Jersey. We met with coastal geologist Dr. Sue Halsey, and interviewed folks that were affected by Superstorm Sandy. The most informative portion of our trip was on Saturday, and we went into the field on Sunday, driving along most of the barrier island. The first place we visited was a famous boathouse along the river. The owners showed us around and pointed out the renovations made to the house after Sandy passed through. They pointed out their heating system that was suspended from the ceiling to avoid damage as well as their newly elevated deck to avoid excessive damage to the dock’s and boathouse’s foundation.

After visiting e boathouse, Dr. Halsey gave us a very detailed tour of homes that were affected on New Jersey’s coast as well as along the river banks. We worked started in Toms River, made our way to Lavalette, and traveled north to Mantoloking.

(boathouse)

(boathouse)

Lavalette is a town on the barrier island, meaning it was much more exposed to damages done by the ocean. Barrier islands are interesting because they are surrounded by water on both the eastern and western parts of them, but exist as a means of protection for the mainland. I examined New Jersey on a map multiple times, and it astonishes me that the barrier island can really fit as many homes as it does. It was extremely different actually being on the island versus seeing its size on a map. In Lavalette, we visited one of our interviewee’s homes, who lives only about 6 houses down from the shoreline. The family’s house was severely damaged by the end of the storm surges. Our interviewee relayed to us that when her husband got up around 1:00 AM, he immediately rolled into water and had to find his way to the roof of their house.

(dunes in Lavalette)

(dunes in Lavalette)

We walked down to the beach and examined the dunes that were rebuilt after the storm, and after that, we took the van up along the barrier islands to examine similar formations. What I found interesting was that in the suburbian areas like Lavalette, there were many anecdotes about having to wait months for reconstruction of both homes and dunes while homes in more wealthy areas like Mantoloking, NJ received immediate aid. This brings up the concern that disaster relief is class-reliant meaning those that cannot necessarily afford aid at the time will be more prone to harm than those of higher socioeconomic class.

(newly raised home in Mantoloking)

(newly raised home in Mantoloking)

A Documentary Discussion

May 26, 2016

Over the past few days, my group and I have visited the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant and have interviewed a number of people varying from professors alive at the time of the incident to leaders of nuclear watchdog groups. These experiences allowed me to have a greater insight into the way people of the United States interact with nuclear disaster. We made sure to ask basic questions inquiring about where they were at the time of the incident as well as more thought-provoking ones about their positions on having a nuclear power plant right in Central Pennsylvania’s backyard. We made sure to keep these interviews private in order to conceal their identities. I will go further into detail about my interview experience when we do our first interview in New Jersey or Japan as I would like to compare/ contrast my experiences across cultural borders (even within the U.S.).

What struck me the most throughout these past few days have been the number, or lack thereof, of minority stories and/or representation in both the nuclear industry as well as the introductory videos our class had today about The Tōhoku earthquake, tsunami, and resulting nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant. Specifically, in a NOVA special our class watched today on Tōhoku, all of the scientists and journalists were, well, western males that were from either the United States or other western countries such as Great Britian. This does not bother me too much on a usual basis as access to scientific information is often only accessible to those that have the income or social privilige to do so. However, the documentary was made in order to inform the public about a natural disaster that killed over 15,000 Japanese individuals, and yet, none of the scientists, journalists, or spokespeople were of Japanese origin. Even more so, there was only one interview of an elderly Japanese farmer couple that lived significantly farther away from the disaster than other potential interview candidates. Yes, there exists certain limitations that may not be controllable towards choosing interviewees for an American documentary. For instance, Japan and the United States have not necessarily had the best past in terms of diplomatic relations and other politics, and individuals may have been sensitive towards being interviewed after such a devastating series of events, but I am sure there existed at least a single voice that was willing to reach out and share their story. In addition to this, many filmographic techniques were used to make the documentary dramatic and entertaining such as camera angles and music choice.

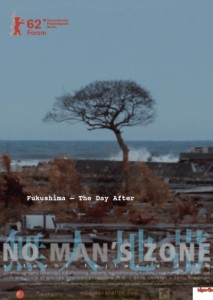

Luckily, the next documentary we watched was entitled, “No Man’s Zone,” which is a documentary done by and for the Japanese people.

This documentary was very raw, and the female narrator incorporated comments that helped the viewer understand the situation at hand. For instance, she mentioned in the beginning of the film that it was difficult for a cameraman to film in a certain area because of the emotional burden attached to stepping on fresh rubble and potentially, a human body. The narrator also incorporated many philosophical comments on the nature of humans. For example, she critiqued society as she stated that people sometimes tend to leave devastating images out of the discussion of the aftermath of disasters because of an innate fear humans have of death. The documentary also consisted of dozens of interviews of Japanese people, both anonymous and not.

Some may see the tactics used in this film as “dramatic,” but I would like to challenge that thought. Is it dramatic because it surpasses the westernized perceptions and expectations we have of documentation, especially concerning natural disasters? Is it dramatic because a woman is the narrator and not a man? Was it dramatic because the images were raw and of rural areas that would not normally have been displayed and represented?

This series of examinations I’ve had can quite literally go on forever, so I would like to conclude on that thought. Perhaps this documentary was not entirely scientific, but it did provide me with an additional lens that I longed for when learning about the Tōhoku region and the Fukushima disaster. Maybe the supreme form of a documentary will contain both diverse narratives and raw imagery as well as information on the scientific processes that occurred during the event, and maybe a clash between the two will never allow us to reach that point.

Hey there!

May 26, 2016

Hello there! My name is Hayat Rasul, and I am from Granada Hills, LA, California. I am a rising sophomore here at Dickinson College. As a first year last semester, I was involved in eXiled Poetry Society, Feminist Collective, Liberty Caps Society, Muslim Student Association, and the Posse Foundation. I am a Mathematics and Earth Sciences double major. Because you really wanted to know, my favorite color is orange and my favorite animal is the snail. Beyond that, I chose to study in this course because of its focus on natural and non-natural disasters and how different communities react to them. Also, as a Californian, quakes and frequent seismic activity have been programmed into my interests as a scientist. I hope to gain knowledge about the differences between the disaster coping cultures within Japan and the United States as well as disaster awareness and preparedness and the way intersectional and diverse identities are involved.

.