Introduction

This project focuses on changing notions of American women’s roles and sexuality from the beginning of the Progressive Era in the 1890s through the 1950s. This time period reflects 70 years of social transformations for American women of all races, ages, and social classes. Females’ spheres expanded outside of the home and into the workforce, higher education, and newfound social lives. Female sexuality became more fluid and allowed for a “New Woman” to emerge: an independent, educated, workforce-bound female who sought radical social change and equal rights for women. World War I and World War II opened up space for women in male-dominated industries and work fields, further pushing the limits of a changing society. Although many females were partially excluded from the progressive change that upper and middle-class white women experienced in this era, including African American women, lower-class women, mothers, and elders, all women experienced new opportunity and freedom in some form. Evidently, the expansion of women’s home sphere into other realms, fueled by progressivism, transformed American society and created a movement that would continue into the modern-day.

The transformation of American women’s roles and sexuality gained momentum during the Progressive Era, which lasted from 1890 to 1920. This was a period of social activism and political reform that focused partly on women’s rights and new functions in society outside of the traditional home. In the late 19th century, many families decreased in size, specifically white, native-born families. Urbanization led parents to consider having less children to reduce living costs. Additionally, new medical advances that reduced infancy mortality rates caused families to have fewer kids, knowing that most of them would survive. An “emphasis on individualistic and democratic values” emerged for both males and females.[1] Growing economic opportunities for white, middle-class women allowed them new freedoms in the workforce. As a result, the relationship between husband and wife became a shared role of decision making, although responsibility for child care and housework remained a female’s task. By 1909, “the woman’s pledge to obey her husband had been dropped from civil marriage vows”. [2] This change represented a shift in the power dynamics of married couples: females were gaining more autonomy. Additionally, marriage was viewed more as a romantic relationship based on mutual respect, causing the divorce rates to soar as marriages lacking affection failed. Despite these new freedoms for females, many women remained subordinated within traditional families. [3]

Women’s sexuality also transformed with the advent of the 20th century. While the 19th century led to changing notions of women’s sexuality, in the early 20th century women also began to reject the social and institutional controls that suppressed their sexual freedoms. For example, traditional Victorian values suggested “firm control of sexual impulses” and the “centrality of reproduction” to sexual activity for white middle and upper-class females. [4] This notion was supported by nativists of the Eugenics Movement in the 1920s, who encouraged Anglo-Saxon women to have children and avoid “Race Suicide” due to the influx of immigrant families in the early 20th century. On the other hand, poor whites and women of color “had the role of providing sexual service to men and domestic service to women,” as well as reproducing the labor force. [5] African American women in particular were overly sexualized. Evidently, ‘sexual freedom’ meant something different for women of different races and social classes.

A group deemed ‘sex radicals’ sought to free women from the societal confines of sexuality. They viewed sex as something to be enjoyed, not moderated. Additionally, they fought the notion of marriage as a social institution to bring up children and instead focused on the intimacy and love involved with marriage. [6] The flapper became a key marketing image of sexual liberation during the Roaring 20’s. She was imagined as a young, white female with androgynous features who was free from traditional sexual constraints. Further, working class black women gained visibility of their sexual movement through blues music of the 1920s and 1930s. Singers like Bessie Smith and Lucille Bogan “protested patriarchal objectification of women and asserted desire directly” in their songs.[7] African American working-class women were focused on the link between sexual autonomy and economic and physical security due to their issues with “poverty, hard labor, sexual abuse, and racist conditions”. [8]

Traditional sexual ideals also emphasized abstinence over birth control, but with more women having extramarital sex and sexual relations without the goal of child-bearing, contraception education and access became a key issue. Margaret Sanger was a significant advocate of birth control during this time period, sending information about contraceptives through the mail and opening a clinic in Brooklyn. [9] Sanger eventually partnered with the Eugenics Movement, promoting childbearing for Anglo-Saxons and providing birth control to others. This gave her birth control push more legitimacy and financial support from traditionally-minded Americans. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the birth control movement garnered greater support due to the inability of many families to support additional children. Overall, the early 20th century planted the seed for the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, which led to abortion rights through Roe v. Wade and the fight for passage of an Equal Rights Amendment to ensure that equality of rights would not be denied on the basis of sex.

The significance of work to women during the Progressive Era was massive: it represented a pathway to individualism, which was a far cry from the “self-sacrificing, self-exploitative work” of the household. [10] Mainly white women entered the workforce for various reasons, including economic necessity, a desire for equality to men, and a way to contribute to society, among other motives. At this point in time, many women of color had already entered the workforce and held unskilled positions with low pay and poor conditions. As a result of many white female’s entrance into the workforce, the figure of the “New Woman” came into the mainstream. This woman was usually imagined as a white female who “opted for work which would ensure her independence from family and reflect her individual interests and capabilities”.[11] On the other hand, African American women had difficulty finding employers that would hire them, partly due to the anticipated dissatisfaction of white customers with black workers. As a result, most women of color worked domestically and in unskilled positions. Due to the difficulties faced by all women in the workplace, multiple women’s trade unions emerged. They were organized into the Women’s Trade Union League, founded in 1903. These groups, including the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, involved mostly white women, and were divided over whether or not to include women of color. Consequently, the National Association of Colored Women formed to focus on racial protection and advancement for African American women. Its president was Mary Church Terrell.

The women’s suffrage movement gained support in the 1910s as upper and middle-class white suffragists worked with working-class women to stage door-to-door campaigns and public speaking on female suffrage. Individual states slowly granted female voting rights, such as Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Idaho, which all established female suffrage prior to 1900. Other goals of the women’s movement, such as equal rights and economic opportunity, were pushed aside to focus solely on voting rights. Oppositionists referred to female suffragists as ‘suffragettes,’ some of them worried of a potential female crusade to prohibit alcohol. Others feared female anticorruption campaigns in the workplace, minimum wage laws, disruption of disenfranchisements of blacks, and the “New Woman” who was moving outside of her traditional role in the home. The 19th amendment was eventually ratified in 1920, signaling a new opportunity for women to contribute to political change. During the “Roaring Twenties” women were eager to participate in their new public responsibilities and debated over whether to join the Democratic or Republican party. Some supported the urban liberalism of Democrats, and others joined nonpartisan groups, such as the League of Women Voters. [12] A small number of women gained roles in local government, and a handful were elected to the House of Representatives.

In the 1930s, Roosevelt’s New Deal and presidency opened up opportunities for women in government. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt turned her role into a “base for political action,” speaking out on public issues and working to “enlarge the scope of the New Deal in areas like civil rights, labor legislation, and work relief.” [13] Even though women gained power in national politics, organized feminism had splintered into many groups with different goals, slowing the movement for women’s rights. As the U.S. entered World War II after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor and American men went off to war, females of all races, ages, and social classes entered the workforce in massive numbers. The War Manpower Commission and the Office of War Information glamorized the working women through characters like Rosie the Riveter, portrayed as “strong, competent, and courageous”. [14] As World War II ended, these images disappeared along with many jobs for females. However, the progressive movement for women’s rights would continue into the 1950s as females became involved in leftist politics, fighting sexism and workplace exploitation. [15] As a whole, notions of female’s roles and sexuality was ever-changing from the beginning of the Progressive Era through the 1950s.

[1] John Whiteclay Chambers II, The Tyranny of Change: America in the Progressive Era, 1890-1920 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press), 90-101.

[2] Chambers, The Tyranny of Change: America in the Progressive Era, 1890-1920, 90.

[3] Chambers, The Tyranny of Change: America in the Progressive Era, 1890-1920, 92.

[4] Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 55.

[5] Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 71.

[6] Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 72.

[7] Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 78-79.

[8] Christina Simmons, Making Marriage Modern: Women’s Sexuality from the Progressive Era to World War II. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 96.

[9] Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty: An American History (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2017), 714.

[10]LeeAnne Giannone Kryder, “Self-Assertion and Social Commitment: The Significance of Work to the Progressive Era’s New Woman,” Journal of American Culture 6, no. 2 (1983): 25-30.

[11] Kryder, “Self-Assertion and Social Commitment: The Significance of Work to the Progressive Era’s New Woman,” 25.

[12] Lynn Dumenil, “The New Woman and the Politics of the 1920s,” OAH Magazine of History 21, no. 3 (2007): 22-26.

[13] Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty: An American History (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2017), 845.

[14] Bilge Yesil, “‘Who Said This is a Man’s War?’: Propaganda, Advertising Discourse and the Representation of War Worker Women during the Second World War,” Media History 10, no. 2 (2004): 103-117.

[15] Kathlene McDonald, Feminism, the Left, and Postwar Literary Culture (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

Primary Source Exhibit

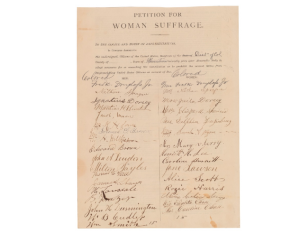

Petition for Woman Suffrage from Colored Men and Colored Women, Residents of the District of Columbia, 1877. Petition.

This petition for female suffrage was created in 1877 in D.C. and signed by 18 African American men and 15 African American women. Among the signers are Frederick Douglass Jr. and his wife. The petition directly addresses the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. The aim of the petition is to persuade Congress to amend the Constitution to prohibit states from disenfranchising citizens based on their sex. This source connects to the suffrage movement for women that ended with the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920, effectively granting female citizens the right to vote. Further, it relates to African American women’s struggle to gain the same rights as white women within social movements of the early 20th century.

Petition for Woman Suffrage from Colored Men and Colored Women, Residents of the District of Columbia. Petition. D.C.: 1877. From the United States House of Representatives, History, Art, & Archives. https://history.house.gov/Records-and-Research/Listing/pm_012/

Mary Gray Peck, “Rise of the Woman Suffrage Party,” 1911. Article.

This newspaper article by Mary Gray Peck was published in Chicago in 1911 in Life and Labor. Peck describes the Woman Suffrage Party as an inclusive movement to enfranchise women. Furthermore, Peck emphasizes that the Party’s goal extends beyond solely suffrage for women to the entrance of women into the world of politics and their increased opportunities derived from suffrage. These include education and mobilization in the workforce. Throughout the article, Peck details the establishment of the Woman Suffrage Party in various states such as California, Pennsylvania, and New York. The intended audience of the piece is individuals who support the enfranchisement of females and wish to learn about the roots of the Woman Suffrage Party. Peck’s piece intends to inform these individuals and garner support for the suffrage movement through examples of recent development in the aforementioned states. This relates to women’s social movements because it depicts part of the women’s suffrage movement.

Peck, Mary Gray. 1911. “Rise of the Woman Suffrage Party.” Life and Labor, June 1911.

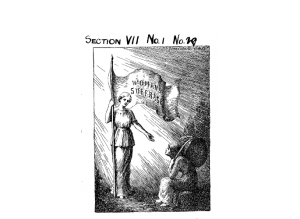

Agnes E. Ryan, The Torch Bearer: A Look Forward and Back at the Woman’s Journal, the Organ of the Woman’s Movement, 1916. Image in Pamphlet.

This 1916 pamphlet created by Agnes E. Ryan and published in Boston includes an image of a woman holding a flag that reads ‘Woman’s Suffrage’ in front of a woman knelt down. The pamphlet, found in the Library of Congress, is the culmination of weekly papers about women’s fight for equality and suffrage. The intended audience of the image is women who may be doubting the necessity of suffrage. The source’s purpose is to highlight the bright future that suffrage will lead to for women, evidenced by the lightness surrounding the women holding the flag. Conversely, the women knelt down carrying a sack is constrained by domestic work. The standing women’s outstretched hand signifies a call for all women to join the suffrage movement. This source connects to changing women’s roles because it signifies the imminence of the ratification of the 19th amendment, granting women the right to vote.

Ryan, Agnes E. The Torch Bearer: A Look Forward and Back at the Woman’s Journal, the Organ of the Woman’s Movement. Image in Pamphlet. Boston: Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News, 1916. From Library of Congress, National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n0024/?sp=1&st=grid

Margaret Sanger, “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda,” 1921. Article.

“Seemingly every new approach to the great problem of the human race must manifest its vitality by running the gauntlet of prejudice, ridicule and misinterpretation. Eugenists may remember that not many years ago this program for race regeneration was subjected to the cruel ridicule of stupidity and ignorance. Today Eugenics is suggested by the most diverse minds as the most adequate and thorough avenue to the solution of racial, political and social problems. The most intransigent and daring teachers and scientists have lent their support to this great biological interpretation of the human race. The war has emphasized its necessity.

The doctrine of Birth Control is now passing through the stage of ridicule, prejudice and misunderstanding. A few years ago this new weapon of civilization and freedom was condemned as immoral, destructive, obscene. Gradually the criticisms are lessening-–understanding is taking the place of misunderstanding. The eugenic and civilizational value of Birth Control is becoming apparent to the enlightened and the intelligent.

In the limited space of the present paper, I have time only to touch upon some of the fundamental convictions that form the basis of our Birth Control propaganda, and which, as I think you must agree, indicate that the campaign for Birth Control is not merely of eugenic value, but is practically identical in ideal, with the final aims of Eugenics.

First: we are convinced that racial regeneration like individual regeneration, must come “from within.” That is, it must be autonomous, self-directive, and not imposed from without. In other words, every potential parent, and especially every potential mother, must be brought to an acute realization of the primary and central importance of bringing children into this world.

Secondly: Not until the parents of the world are thus given control over their reproductive faculties will it ever be possible not alone to improve the quality of the generations of the future, but even to maintain civilization even at its present level. Only by self-control of this type, only by intelligent mastery of the procreative powers can the great mass of humanity be awakened to the great responsibility of parenthood.

Thirdly: we have come to the conclusion, based on widespread investigation and experience, that this education for parenthood and of parenthood must be based upon the needs and demands of the people themselves. An idealistic code of sexual ethics, imposed from above, a set of rules devised by high-minded theorists who fail to take into account the living conditions and desires of the submerged masses, can never be of the slightest value in effecting any changes in the mores of the people. Such systems have in the past revealed their woeful inability to prevent the sexual and racial chaos into which the world has today drifted.

The almost universal demand for practical education in Birth Control is one of the most hopeful signs that the masses themselves today possess the divine spark of regeneration. It remains for the courageous and the enlightened to answer this demand, to kindle the spark, to direct a thorough education in Eugenics based upon this intense interest.

Birth Control propaganda is thus the entering wedge for the Eugenic educator. In answering the needs of these thousands upon thousands of submerged mothers, it is possible to use this interest as the foundation for education in prophylaxis, sexual hygiene, and infant welfare. The potential mother is to be shown that maternity need not be slavery but the most effective avenue toward self-development and self-realization. Upon this basis only may we improve the quality of the race.

As an advocate of Birth Control, I wish to take advantage of the present opportunity to point out that the unbalance between the birth rate of the “unfit” and the “fit”, admittedly the greatest present menace to civilization, can never be rectified by the inauguration of a cradle competition between these two classes. In this matter, the example of the inferior classes, the fertility of the feeble-minded, the mentally defective, the poverty-stricken classes, should not be held up for emulation to the mentally and physically fit though less fertile parents of the educated and well-to-do classes. On the contrary, the most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the over-fertility of the mentally and physically defective.

Birth Control is not advanced as a panacea by which past and present evils of dysgenic breeding can be magically eliminated. Possibly drastic and Spartan methods may be forced upon society if it continues complacently to encourage the chance and chaotic breeding that has resulted from our stupidly cruel sentimentalism.

But to prevent the repetition, to effect the salvation of the generations of the future–nay of the generations of today–our greatest need is first of all the ability to face the situation without flinching, and to cooperate in the formation of a code of sexual ethics based upon a thorough biological and psychological understanding of human nature; and then to answer the questions and the needs of the people with all the intelligence and honesty at our command. If we can summon the bravery to do this, we shall best be serving the true interests of Eugenics, because our work will then have a practical and pragmatic value.”

This 1921 piece by Margaret Sanger, published in New York, is found in the Birth Control Review. It outlines the connection between birth control and eugenics, a partnership Sanger formed to gain legitimacy and financial aid from conservative groups. The Eugenics Movement aimed to eliminate negative traits through the reproduction of specific populations. Undesirable populations included poor whites and minorities. Sanger appeals to eugenicists by suggesting that birth control can stifle birth rates of undesired populations. In terms of desired Anglo-Saxon individuals, Sanger reminds them of their responsibility to have children. Sanger’s intended audience is individuals who support the Eugenics Movement and wish to marginalize poor whites and minority groups. This source connects to changing women’s roles because it highlights the marginalization of certain groups through the combination of the Eugenics Movement and the Birth Control Movement. Rather than encouraging all women to take control of their sexual health, Sanger solely focuses on undesired groups to appeal to Eugenicists.

Sanger, Margaret. “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda.” Birth Control Review. New York: Birth Control Review, 1921. From the Public Writings and Speeches of Margaret Sanger, Margaret Sanger Microfilm. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/webedition/app/documents/show.php?sangerDoc=238946.xml

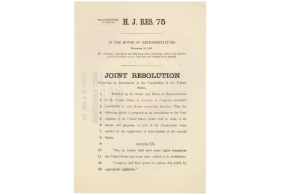

H.J. Res. 75, Proposing an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, 1923. Legislation.

The Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was first introduced in 1923. Drafted by Alice Paul, a women’s suffragist, the ERA aimed to affirm equal rights for male and female citizens. While the ERA initially gained support after its introduction, it failed ratification in 1982. It was reintroduced in the subsequent Congresses without passage. Its failure was largely due to the work of the Stop ERA movement, led by Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative lawyer. The Stop ERA movement argued that women were already protected under law, and that the ERA would deprive women of their privileges. As a whole, the Equal Rights Amendment reflects the push in the 1920s for equal rights for women and an era of social change.

National Archives Catalog. H.J. Res. 75, Proposing an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, 1923. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7452156

Lucille Bogan, Shave ’em Dry, 1935. Song.

Lucille Bogan’s 1935 song Shave ‘em Dry, recorded in New York City, shows how female blue singers worked to sexually liberate black women through their lyrics. Bogan, an American blues singer and songwriter, expresses her sexuality directly in Shave ‘em Dry and normalizes the taboo topic of sexual pleasure. She refers to unrestrained sexual acts and the goal of pleasure from sex, rather than childbearing. The intended audience of the song is primarily black women of the 1930s who wished to refute their over-sexualization by white men and women while also asserting their ability to bring men pleasure. Bogan’s song relates to changing notions of women’s sexuality by candidly describing the gratification of sex, specifically for black women.

Bogan, Lucille. Shave ‘em Dry. Sound recording. New York: Columbia Records, 1935. From YouTube.

Howard R. Hollem, “Riveter at Work on Consolidated Bomber, Consolidated Aircraft Corp., Fort Worth, Texas,” 1942. Photograph.

This 1942 photograph by Howard R. Hollem depicts a ‘Riveter,’ or a World War II era working woman, building a consolidated bomber in Fort Worth, Texas. The image connotes women joining the workforce as a duty to their nation during the war. The intended audience of this photograph is women interested in joining the workforce. It aims to mobilize women into mostly industrial positions left vacant by men who went to war. Photographs like this appeal to 1940s-era women’s desire to break out of the domestic sphere and experience the independence of work life. This source relates to the movement of mainly white, middle and upper-class women into the workforce during World War II to fill soldier’s positions.

Hollem, Howard R., photographer. “Riveter at work on Consolidated bomber, Consolidated Aircraft Corp., Fort Worth, Texas.” Photograph. Fort Worth: 1942. From Library of Congress, Office of War Information Color Slides and Transparencies Collection. https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsac.1a34953/

Bernard Devoto, “The Flapper’s Revolution,” 1946. Article.

This 1946 article by Bernard Devoto, an American historian and defender of civil liberties, reflects on the emergence of the “flapper” and the resulting social changes for women. Devoto describes this new “model” of women, the flapper, as physically capable of keeping up the men in sports, confident in her body, and less sex-conscious than women of the past. Further, Devoto highlights that the flapper broke moral and sexual taboos by speaking directly and frankly about sex. This article’s purpose is to describe the era of the flapper and the impact of the flapper on the way females acted during the 1920s and onward. Its intended audience is individuals looking to trace changes in women’s sexuality and roles within women’s social movements of the early 20th century.

Devoto, Bernard. “The Flapper’s Revolution.” Woman’s Day. New York: Hearst Magazines, 1946. From Women’s Magazine Archive. https://search.proquest.com/wma/docview/18140 . 80100/fulltext/BA4E220C0F064F4CPQ/1?accountid=10506

“NACW Sets Year’s Goals,” 1949. Article.

The National Association of Colored Women’s goals for the year are outlined in this 1949 article from the Baltimore Afro-American. The NACW was a federation of local black women’s clubs which rallied for women’s suffrage, desegregation, and the general improvement of the status of African American citizens. This article outlines the yearly goals of the NACW, which include making national state headquarters a clearinghouse for information on legislation and family life, among other things. Additionally, the article cites that the NACW aims to raise funds for the Hallie Quinn Brown college scholarship fund and recruit more young women and girls as members of the NACW. The purpose of this article is to highlight the goals of the NACW and garner support for them. It targets both current NACW members and younger black women and girls who may be interested in joining. This article relates to changing notions of women’s roles because it specifically encourages young women to join the NACW to fight for women’s rights for African American females.

“NACW Sets Year’s Goals.” Baltimore Afro-American, September 17, 1949. https://search.proquest.com/docview/531671345/70AFB973564C41C0PQ/15?accountid=10506

Margaret Sanger, “The Humanity of Family Planning,” 1952. Article.

Margaret Sanger wrote The Humanity of Family Planning for the Third International Conference on Planned Parenthood in November of 1952. The piece was published in 1952 under the Family Planning Association of India in Mumbai. It was located in the primary source database Women and Social Movements, International – 1840 to Present. As the co-director of Planned Parenthood at the time, Sanger addresses the necessity of available birth control worldwide. The purpose of the piece is to argue that the issues of overpopulation, child poverty, child labor, and high crime rates across the world could be solved with accessible birth control. Sanger also underlines that young married women, women with diseases, and women lacking a stable income should consider birth control. Sanger directly addresses public health and social welfare officials worldwide, calling on them to help citizens with family planning. Further, Sanger warns couples to have children responsibly and only if they are fit. This piece connects to changing women’s roles and sexuality between 1890 and 1960 because it intends to stimulate social change around the birth control movement.

Sanger, Margaret. “The Humanity of Family Planning.” Mumbai: Family Planning Association of India, 1952. From Women and Social Movements, International – 1840 to Present, Women and Social Movements, International. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/ bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C1739392#page/1/mode/1/chapter/bibliographic_entity|bibliographic_details|1739392