Plessy v Ferguson

This primary source is a document of the supreme court case from Plessy V. Ferguson. This case was between an African American man Plessy who bought a first-class ticket and sat in a whites-only then was asked to move to another spot by a white conductor because he was not white. After he refused, he was then thrown of out the train which later led to his arrest. The Supreme Court ruling provided legal justification for segregation on trains and buses, and in public facilities, such as hotels and schools. I found this document very useful because the decision, in this case, upheld the principle of racial segregation and also it showed how one decision from the Supreme Court of “separate but equal” set back civil rights in the United States for decades. This case was important because it later was also used to make the judgment in the case of brown or board of education giving African American right to attend white schools.

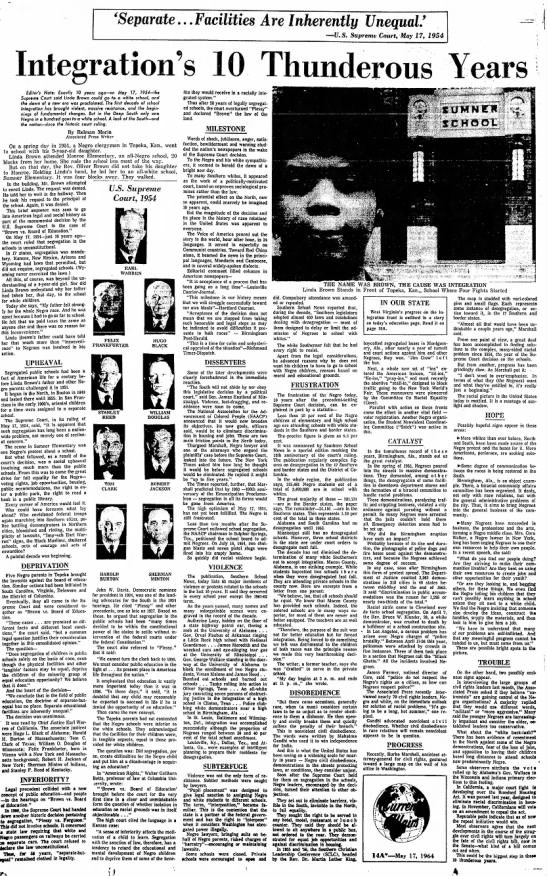

Brown v Board of Education

This is a 1969 newspaper highlighting the 1954 Supreme Court case of Brown vs. Board of Education. This newspaper was published 15 years after the case and it stated that the acceptance of Linda into a white institution led to violence. This famous case started with an African American who was denied by the school next to her house because she was black. She was sent to another school far away from her house. Oliver, the father took the issue to the court which later, the case ended up at the supreme court of united states. I found this source helpful for my project because it covers a lot of the problems I’m defining in my project and this specific case change segregation schools in the united states, especially in the south. This case identifies that racial segregation in public schools as a violation of the fourteen amendments of the constitution.

Sweatt v. Painter

Sweatt v. Painter Trial Documents, pt 1.

- [1][fol. 1]IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF TRAVIS COUNTY, TEXAS, 126TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT

- No. 74,945

- Heman Marion Sweatt, Relator vs. Theophilis Shickel Painter, et al, Respondents

- Statement of Facts

- Before Hon. Roy C. Archer, Judge.

- Appearances:

- Mr. W. J. Durham, Mr. Thurgood Marshall, Mr. E. B. Bunkley, Jr., Mr. James M. Nabrit, Jr., .Counsel for Relator. Mr. Price Daniel, Attorney General of Texas; Mr. Jackson Littleton, Asst. Atty. Gen. of Texas; Mr. Joe Greenhill, Asst. Atty. Gen. of Texas, Counsel for Respondents.

- Be It Remembered that on Monday, May 12, 1947, and succeeding days, all in the Regular March Term of said Court, there came on to be heard the above entitled and numbered cause; whereupon the Court admitted into evidence the following: [fol. 2-7]

- After Session

- May 12,1947 2:00 P. M.

- Statement By The Court:

- The Court: It seems this morning that perhaps I wasn’t as clear in making a statement of this trial as perhaps I should have been. This case was tried here on stipulations and on some testimony other than stipulations and went to our Court of Civil Appeals, and by agreement of all parties, the Court of Civil Appeals entered an order in which this cause was remanded generally to this Court for further proceedings, without prejudice to the rights of any party to this cause. I think we needed that additional explanation. If we are ready now, we may go ahead.

- Mr. Durham: Relator is ready, Your Honor.

- The Court: Are you ready, Mr. Attorney General?

- Mr. Daniel: Yes.

- Thereupon counsel for relator and counsel for respondents presented to the Court a statement of their respective pleadings in this cause.

- The Court: I think with the trial being had before the Court we will be able to hear your testimony and at the same time bear in mind your exceptions on either side. So, for the time being, I am just going to carry your exceptions along in the trial of this case. If at a later time it requires a little more time on your part to prepare to meet issues that may be raised, which might be somewhat of a surprise to [fol. 8] you, the Court will give you that time.

- Mr. Durham: To save time, I thought we could go on with our testimony, we could go on this evening, and maybe talk about the stipulations after Court adjourns.

- Mr. Daniel: Just so it is understood, we have no stipulations at this time.

- Mr. Durham: That is right, we have no stipulations at this time.

- The Court: I haven’t heard it if you have.

- Mr. Durham: It is agreed that respondents will put their testimony on first, and then we will put our testimony on, but in the record as it is made up, the relator’s testimony will come first in the record.

- The Court: All right.

- Reporter’s Note:—By agreement of counsel later, this statement of facts was ordered prepared setting out the testimony and proceedings in chronological order.

- Mr. Daniel: Your Honor, we have a witness that we want to put on out of order, and I believe it is agreed we may do that.

- The Court: All right.[3]

- D.A. Simmons, a witness produced by Respondents, having been by the Court first duly sworn as a witness testified as follows:

- [fol. 9] Direct examination.

- Questions by Mr. Daniel:

- Q. State, your name.

- A. D.A. Simmons.

- Q. Where do you reside, Mr. Simmons?

- A. Houston, Texas.

- Q. What profession are you in?

- A. Attorney at law.

- Q. Do you hold a law degree?

- A. I do.

- Q. From what school?

- A. The University of Texas Law School.

- Q. Do you hold any other law degrees?

- A. I have an Honorary Doctor of Law degree from the University of Montreal and an Honorary Doctor of Law degree from Loyola University in New Orleans.

- Q. How long have you practiced law?

- A. Twenty-seven years.

- Q. Have you during that time had any official association with The American Bar Association?

- A. I have.

- Q. Would you please state your official connection with the American Bar Association?

- A. Well, if I may, I would like to go just a little back of that, because I understand I am called—I know nothing about the case, but I am called on as a witness on certain [fol. 10] phases of the American Bar standards.

- The Court: Yes.

- A. I have been President of the Houston-Galveston Bar Association, 1932 and 1933. I was President of the Texas Bar Association in 1937 and 1938. I was President of the American Judicature Society in 1940 and 1942. For the record, I would like to state the American Judicature Society is the second largest national organization of lawyers in the country, and I was President of the American Bar Association in 1944 and 1945, heretofore been on the Board of Governors for five years. [4]

- Q. Have you in your American Bar Association work had occasion to be on any boards that inspected law schools or passed upon the requirements of whether or not certain law schools met requirements of the American Bar Association?

- A. The standards of the American Bar Association are set by the House of Delegates. They are recommended by the Board of Governors and the Section of Legal Education. I have been a member of the Board of Governors in 1937 to 1940, and 1944 to 1946. I have been a member of the House of Delegates representing the lawyers of Texas, 1936 until today. I am still a member.

- Q. In your experience with the American Bar Association, I will ask you if you have ever had occasion to study the standards of the American Bar Association as far as law [fol.ll] schools are concerned?

- A. Yes, sir, I am familiar with them. I was a member of the House when they were voted.

- Q. You are acquainted with the standards as they exist today?

- A. Yes, sir.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the physical facilities, the faculty, library, courses of instruction, and other matters related to the University of Texas School of Law?

- A. Well, I would say that since I was graduated there in 1920, my late visits, I have not counted the law books. I know they have a very substantial law library. I do not know how many books, and I know a good many of the professors, and I am familiar in a general way with the course of instruction.

- Q. Do you know whether or not the University of Texas Law School meets the standards of the American Bar Association for an accredited law school?

- A. It is an approved school.

- Mr. Durham: We object to that because it is an assumption of what those standards are. The witness hasn’t testified what the standards are. It is assuming what the standards are.

- The Court: I believe I will let him proceed, Counselor, along this line. You will save your point, and maybe we will get back to it. [5]

- A. My answer is: It is an approved law school. It has [fol. 12] been inspected and approved by the House of Delegates of the American Bar Association as having complied with the standards.

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. Are you acquainted-

- A. I can say what the standards are, briefly.

- Q. Will you briefly state what the standards are?

- Mr. Marshall: I think the standards are the best evidence.

- A. I think so.

- The Court: The standards are.

- A. I assume that counsel on both sides have them.

- Mr. Marshall: Unfortunately, if Your Honor please, we do not have them, except that one person on our staff has them, and he is not in the court room at this time.

- The Court: All right.

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. I will ask you if this page contains the standards of the American Bar Association with reference to approved schools?

- A. That is the copy of the standards as approved by the House of Delegates of the American Bar Association.

- Mr. Daniel: We wish to offer it. We offer from page 1. It is headed, “Standards of the American Bar Association.”

- Q. I believe your testimony was that the University of Texas Law School has been approved as having met those standards?

- [fol. 13] Said instrument was admitted in evidence as Respondents’ Exhibit No. 1.

- A. That is correct.

- Q. Now, I will ask you, Mr. Simmons, at my request, whether or not you have inspected the law school for the State University for Negroes here, adjoining the Capitol grounds in Austin?

- A. Dean McCormick, of the Texas University Law School, took me when the Court recessed this morning to the [6] wing just north of the Capitol, where on the ground floor I found three rooms and a hall and toilet facilities. The first room had three or four or five study desks, a law book case or two with approximately, I would say, one hundred and fifty to two hundred books, and there were two class rooms the Dean pointed out, one with students’ study desks; the other one he said was a reserve room in case more than eight or ten students applied. I saw that. I know where that is. I walked over to the Capitol. I was informed, from the reading of the pleadings this morning, which is all I know about that phase of it. I learned that the Supreme Court Library was made available by the statutes. I have a little familiarity with that from twenty years ago as First Assistant Attorney General. I went back, and the books seemed to have been kept up to date, and it is about a hundred or a hundred and fifty yards from this school.

- Q. You are speaking now of the State Library and the [fol. 14] Supreme Court Library?

- A. Yes, sir; on the second floor on the north side in the Capitol Building.

- Q. And that was about how far from the school?

- A. The north entrance of the Capitol, I would say, was a hundred yards. This is on the second floor immediately above the north entrance.

- Q. How many volumes of law books are required by the American Bar Association for a library that meets its standards?

- A. Well, the standards themselves call for an adequate library. The interpretation of that, to get it down to actuality, has been seventy-five hundred well-selected books with cases, in complete sets.

- Q. I would like to ask you if the Supreme Court Library, with which you say you are familiar, and the State Library there in the Capitol Building, has been kept up to date, and if the evidence shows there are over 40,000 books in that library,—would it meet the requirements of the American Bar Association for a law school library?

- A. Well, I glanced over some of the sets. They are up to date. Whether there are 40,000, I would rather leave to the librarian, but obviously there are a great deal more than 7,500 books, and they are books of a character that would afford an adequate legal education. [7]

- Q. Now then, did you in talking with Dean McCormick [fol. 15] acquaint yourself as to the courses of instruction that are being offered to the law school of the Texas State University for Negroes?

- A. Well, I was merely informed from the set-up, and from the books on the shelves that the freshmen, first year law school courses are the courses that would be available at this time, and that they were the identical books and the identical courses given the first year law students at the University of Texas Law School.

- Q. I will ask you a hypothetical question. If the evidence in this case shows that in the building that you have already inspected, the University of Texas law faculty, the same faculty members, offered the same courses in law in that building, and with the library facilities of the Supreme Court Library that we have mentioned, and if the requirements for entrance are the same, the requirements for graduation are the same, as the Texas University Law School, if the evidence shows that the requirements for classroom study and all requirements contained in the catalogue of the University of Texas Law School must be met in the law school of the State University for Negroes, if the evidence shows what I have recited, in your opinion, will Texas University for Negroes Law School offer equal educational opportunities in law as that offered by the University of Texas?

- Mr. Marshall: If Your Honor please, assuming he is an [fol. 16] expert, and assuming all that is in the hypothetical question, I don’t think this witness is entitled to give a conclusion as to what the law is in the case. I think that is your job.

- The Court: I think he hasn’t asked him a law question. I think he is asking him if, as an expert, it is substantially the same.

- Mr. Marshall: The question was whether it furnishes the equality required.

- The Court: Well, he wouldn’t say whether there is an equality or not.

- Mr. Marshall: May we have an exception, please, sir?

- The Court: Yes, sir. [8]

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. You may answer, please.

- A. In my opinion, the facilities, the course of study, with the same professors, would afford an opportunity for a legal education equal or substantially equal to that given to the students at the University of Texas Law School.

- Q. That is all.

- Cross-examination. Questions by Mr. Marshall:

- Q. Mr. Simmons, what is the purpose of accreditation from the American Bar Association, of law schools?

- A. To make standards—pardon me. Would you mind telling me your name[fol. 17]

- Q. Thurgood Marshall.

- A. And you are from where?

- Q. Originally from Baltimore, and now from New York.

- A. I like to know who I am talking to.

- Q. Good.

- A. The purpose of any standards are to set a goal. The American Bar Association standards are to assure adequate legal education to those who are going to represent the public as lawyers. They are merely recommendations, and as—and your name?

- Mr. Durham: Durham.

- A. As Mr. Durham suggested a while ago, the American Bar Association is a private association of lawyers, about 40,000, and it set up these standards as a guide to the law schools, because when the standards were set up there were a great many law schools in the United States, mainly night schools, that were giving courses that were deemed to be inadequate, inadequate to prepare the lawyers of the future generation.

- Q. And isn’t it true that many studies have been made by the American Bar Association and the officials, including several past presidents, concerning the inferior education obtained in small, part-time law schools? Isn’t that true?

- A. The Association has been concerned with legal education since 1896, and it has made many studies. That part is entirely correct. We are now beginning to engage in a study [fol. 18] that used to be done by the Carnegie Foundation. [9] They used to make an annual survey of legal education, and Mr. Reed of that Foundation, I think, was assigned other duties about ten years ago, and the American Bar Association has taken over that officially.

- Q. Are you using Mr. Reed officially?

- A. No, sir; I happen to know him personally.

- Q. Have you read any of his studies?

- A. I have many of them in my library.

- Q. You are familiar with his viewpoint on part-time law schools?

- A. I would prefer to answer mine. I have studied at night part time law schools myself. I have studied law in every form, I think. I studied in my father’s office as a boy. I came to the University of Texas not having funds to proceed through. I stopped for a couple of years and went to night law school, working in Houston, an unapproved part-time school, with no books except those you could borrow, and I came back after the First World War and came back here, and I believe I am familiar with the office study and small part-time school and the approved law school, and sympathetic with all three.

- Q. As a matter of fact, as of the present time, isn’t the American Bar Association opposed to part-time law schools?

- A. No. [fol. 19]

- Q. Hasn’t the American Bar—

- A. For the night school, what they want is legal education for the future lawyers, and as the small school or the night school obviously can’t give as much time to the student as a day school, full-time, they require that they give four years of three hours in the evening instead of three years like the regular approved schools, but many of the part time schools are approved.

- Q. Do you mean approved by the American Bar Association?

- A. Yes, as having complied with these standards.

- Q. There is another accrediting agency, the Association of American Law Schools?

- A. Yes.

- Q. Isn’t this true; their standards are higher than the American Bar Association’s?

- A. In some instances, I think they are more stringent.

- Q. Isn’t it a fact that there are some schools approved by the American Bar Association that are not approved by the Association ofAmerican law Schools? [10]

- A. I think that is true in some instances. I believe Lincoln University in St. Louis is approved, on our lists—

- Q. It is on both of the sections?

- A. That is the law school, I think. My last check, I think it had 35 students.

- Q. Counting the faculty? [fol. 20]

- A. Take Howard—that is a colored law school at St. Louis. Howard School of Law in Washington, the last time I had occasion to go to that, I believe it had—just before the war, I believe they had about 67 students. It is a fully approved school.

- Q. Both associations?

- A. I think so.

- Q. Yes, sir. Is it not true that accreditation by the American Bar Association is an asset to the school and the pupil and the community?

- A. We hope so.

- Q. And it is your opinion that it is of value to any school?

- A. Yes, sir.

- Q. And would you not, therefore, say that attendance at an unapproved school does not give equal education to attendance at an approved school?

- A. No, I wouldn’t say that, because any school,—all of these schools we have named at one time were on the unapproved list. They had to prove how the facilities may be equal, but the student body, after all, is the one that is going to determine the standing of that school, and if the student body takes advantage of the facilities offered, and by the State Bar examination, which has no relationship to the school itself, passed the State Bar examination, and the students of that school as many in proportion, uphold the [fol. 21] teaching of that school, it is likely, of course, to be approved more readily than one where the product does not stand the gaff of the State examination.

- Q. The American Bar Association waits and watches what the school is doing before they approve it?

- A. Yes, sir.

- Q. They always do that, don’t they?

- A. Yes, sir.

- Q. But you think in the meantime the school still should be giving the same training as an accredited school?

- A. Absolutely. The training is for the individual.

- Q. I understand— [11]

- A. It has got to be from the inside, what the man develops himself, what he can absorb himself. If he has the books and curriculum and physical facilities, the light, the books, the professors, I would venture to say that a student who had — let’s say that school had ten students, with four professors teaching ten students, that the ten students should absorb a great deal more law than with ten instructors teaching seven or eight hundred students.

- Q. They approve the school, the curriculum and the plant?

- A. And the product.

- Q. You don’t just approve it on the product?

- A. No, these standards should show there are seven or eight hundred well-chosen volumes and should have pro-[fol. 22] fessors who are full time professors in the field of law.

- Q. Did you know that these proposed professors for the Negro school are to be part time professors? Did you know that?

- A. I understood they were full time law teachers.

- Q. Did you understand their work there was to be part time?

- A. I would say that with ten students, it would have to be.

- Q. I don’t know what you mean by that.

- A. I was advised by the Dean of the Texas University Law School they will be the same men that teach at the Texas University Law School. They are full time teachers, of course, employed by the State of Texas to teach students in law.

- Q. But we are talking about the so-called Negro school. As to that school, they are part time?

- A. Yes, sir, that is true. They would also be part time at the University of Texas.

- Q. Did you find out where their offices are?

- A. At the other school, but they have a desk here. I was pointed out,—all I know is what I was told this morning, and I told you who told me. I was pointed out the books, the desks, the chairs, and the rooms, and the distance from the State Supreme Court Library, and I went over there to see if it was where it used to be.

- Q. Do your standards of the American Bar Association, in accrediting a school,—isn’t it limited to what is in the school? To be specific—

- A Until students come, this isn’t a school. [ 12] [fol. 23]

- Q. Thank you, sir, but the other question is this. If you have a school, for example; you are familiar with the fact, are you not, that the library in the Library of Congress is one of the best in the country? Are you not familiar with that?

- A. Yes, sir.

- Q. If you had a university in Washington with no law library, but access to the Library of Congress, would you accredit that school?

- A. You are talking to me. I am only one of 185 delegates in the House of Delegates. I do not personally accredit anybody. If the law school you are talking about had trained professors, set up by Congress across the street, a hundred yards from that library, and the Act of Congress said this library shall be the library of that school, I would say, so far as I was concerned, I would say they had been furnished an adequate library, all of the books they could hope to read or study.

- Q. I didn’t say the library was made a part of the school. I said “made available”, like it is to everybody else.

- A. Yes.

- Q. Because it is available, would you, therefore, use that as a part of the accrediting of the school?

- A. Having used this one myself, I know there are not so many people there but what you can always find table space [fol. 24] and all of the books you want to study or read. We are trying to get some law and the standards of the law into the mind and soul of the individual student. I am not trying to build a building for you, or law books. We are trying to build lawyers with character.

- Q. But you do require the building with the law books?

- A. We require, as I said before, we require that a certain number of certain proper law books be available.

- Q. What do you mean by “available”?

- A. You are the one that asked me,—you said a while ago, questions on availability. I will say that any time you have a law library a hundred yards away from your school, and that the Legislature says these books are for the use of that school, that those books are available.

- Q. I think you are familiar with the statute that says they shall be available. Isn’t that the language?

- A. I will let the Judge pass on the statute.

- Q. You are quoting from it? [13]

- A. You were talking about Congress, if the Law Library of Congress was available, and I am trying to define what I mean by available.

- Q. Do you know of any other school the American Bar Association approved that didn’t have a library in the building where the school was?

- A. All I can say is I haven’t inspected over about eight [fol. 25] law schools personally.

- Q. You have been passing on law schools for how many years?

- A. Personally?

- Q. Yes, on the Committee?

- A. On the House of Delegates since it was established in Boston in 1936, and three years before that as a member of the General Council from Texas.

- Q. During that period, has that body approved a law school that did not have a library in the building where the law school was?

- A. I can’t answer that.

- Q. To your knowledge?

- A. All we have ever passed on were—

- Q. Can we first get an answer to that; and then you can go ahead? Do you know, to your knowledge, that—

- A. I can answer that like lawyers do, either way. I don’t know, because the practice is this. Mr. Demuth, of the University of Colorado, and Mr. Sullivan, from the University of Illinois, inspect the schools, and they come back and report to the House of Delegates of the American Bar Association, We have inspected Lincoln University Law School. It has an adequate available library. Nobody has ever said there is one in the building across the street, in all of the years that I have acted as one of those that have passed on it. In the eight schools that I have in-[fol. 26] spected, they all had libraries either in the building, or in adjacent buildings.

- Q. That is the purpose of having libraries in the law schools?

- A. In the school?

- Q. Yes.

- A. To make books available so that the student can study and learn the principles of law.

- Q. Don’t your requirements also require that you have a trained competent librarian? [14]

- A. Someone should be familiar with the books. He doesn’t need to be a full time librarian.

- Q. Do you require that you have a full time dean?

- A. The interpretation that has been made by the Committee before they are recommended to the House of Delegates, the school should have at least one full time professor or dean for each one hundred or fraction thereof, of pupils. We don’t require a full time dean, as you quite well know, Mr. Marshall.

- Q. I don’t know anything about what the American Bar Association requires, because I am not a member of it for one reason.

- A. May I go ahead?

- Q. You may proceed.

- The Court: Until somebody stops you, you can proceed.

- A. This is quite interesting to me. Are you a member of the Lawyers’ Guild ?

- By Mr. Marshall:

- Q. One of the founders of it, and a member of the Board [fol. 27] of Directors.

- A. Are you a member of the National Bar Association of Colored Lawyers’?

- Q. I am a former Secretary for four years of it.

- A. That is a national association of colored lawyers?

- Q. No, sir; it is an association of American lawyers that has no bars as to race, creed, or color.

- A. Is there a single white lawyer in it?

- Q. Yes, sir; Martin Popper, and two or three others that I can name.

- A. Of course, we have colored lawyers in the American Bar Association.

- Q. You had one up until two years ago?

- A. Bill Lewis. That is purely aside. We can go on with the questions. I helped organize The Texas State Bar. We have colored lawyers in that. We have colored lawyers in the American Judicature Society, if that has any place in the record.

- Q. Getting back to the law library, and the American Bar Association. They do require that we have at least one full time dean or full time professor for each one hundred students? [15]

- A. There must be one full time man.

- Q. I will ask you a hypothetical question. If there is a law school established here in Texas for Negroes that has [fol. 28] not a single full time professor or dean, would you say that that gives the type of education that would meet the approval of the American Bar Association?

- A. Well, I am going to have to assume that this law school has some students and there are—

- Q. Assume not less than one hundred.

- A. Lincoln, say, with thirty-one. I would say if, as, and when this school has enough students to require through the business facilities, the efforts of a full time man, they should certainly have one.

- Q. Could that school be approved by the American Bar Association without any full time teacher or dean?

- A. Yes, sir, it could.

- Q. It could be?

- A. Yes, sir; the requirement of one full time professor for each one hundred students isn’t in the standards. It is an interpretation made by the Committee as a recommendation to the House of Delegates.

- Q. So, it would vary?

- A. If the Committee found it was adequate. What is the purpose of having one instructor for each one hundred, or less? The purpose is stated in the standards to be so that the professor will be acquainted with the needs and the studying of the student body. I would assume, and would so state, that if this school has less than 25 students, that [fol. 29] three or four professors who are full time professors, not part time, would certainly seem to be adequate.

- Q. What would be—and maybe you can’t answer this— what would be the minimum number of full time teachers, deans, that you would need?

- A. At this time?

- Q. Yes, sir.

- A. With how many students’

- Q. Well, assume we have one.

- A. Well, I wouldn’t see the slightest need for a full time professor to give his full time to this one student.

- Q. And—then could that one student get the same type of education that other students get by having only the viewpoint of one professor? [16]

- A. I didn’t understand that was to be the case. I understood they were to assign four.

- Q. And you wouldn’t need any full time, then?

- A. I wouldn’t think so. I would think; if he had the same capacity, he could get a better grasp of the principles of law than if he were one of eight hundred students with ten professors.

- Q. Don’t you require, in accrediting schools, that you have a full time professor, or professors, for the purpose of being available to the students during the regular day, throughout the day, for consultation? Isn’t that true? [fol. 30]

- A. No, the purpose, as I stated before, is so that there will be a sufficient number of instructors so that they will personally know each student and be available to encourage and teach him how to study law. Some of them don’t know how to study law.

- Q. I think we are talking about class room work. I am talking about after class. Isn’t that the reason for a full time professor, so that he will be available in the afternoon for consultation?

- A. No; so that they will have some chance to individually and personally know the students.

- Q. And another question; do you know the difference between a law library and a teaching law library?

- A. I don’t know what you have in mind, if that is what the answer is.

- Q. I will explain it. For example, under the requirements, the types of books that you have to have in a law school library aren’t the books that are required, for example, in a Supreme Court Library?

- A. Well, I don’t think so. They lay more stress on the law reviews and things of that kind than the practicing lawyer does; or, I might say, used to, but the Supreme Court Library here has about everything a general practitioner would need.

- Q. Does it have what a law school needs? [fol. 31]

- A. I would say that depends on the course of study. I have known some law schools to give,—I think there is one that gives a course in patent law. I question whether that one would have facilities for teaching much patent law.

- Q. A few others, too. The point I am trying to get at is that the law library is an important feature of a law school, a very important feature? [17]

- A. That is right.

- Q. And the University of Texas Law Library has one of the best; isn’t that true?

- A. It has a very good library.

- Q. And isn’t it fully accredited by every association?

- A. As far as I have heard.

- Q. And does it not have a librarian and an assistant librarian?

- A. Well, they had a librarian when I was there.

- Q. And isn’t it the only library in this section of the country that has microfilm reports of the records of the Supreme Court?

- A. You had better ask the dean.

- Q. If you are going to compare the two; aren’t you forced to compare the two libraries?

- A. I said, in my opinion, the Supreme Court Library, which is one hundred yards from your school, has more than any one, or twenty-five students, would possibly absorb in three years; and if he absorbed that, he would be competent [fol. 32] to start practicing.

- Q. The answer is that the important thing is that it is not the number of books necessarily, but the right books that you will need?

- A. Yes.

- Q. And obviously, there are books at the University of Texas that are not in the library of the Supreme Court?

- A. I can’t answer that.

- Q. There is a larger percent—

- A. I will say that all I have read that qualifies me, if I am qualified to practice law, are in the Supreme Court Library.

- Q. Do I understand you to say that the basis of your testimony is that the individual student can get as much in an inferior school as he can get in a superior school, if he is smart enough?

- A. The inferior and superior are your words. I said, with the same instructors in the two schools, and the law books available in the Supreme Court Law Library, a hundred yards across the street, he can get an adequate legal education, at least as good as that of the student, one of seven or eight hundred, getting the similar courses out at the University of Texas Law School. [18]

- Q. But you don’t think it is a mistake to put all of those books at the University of Texas Law School, do you?

- A. That is not up to me to judge that. I haven’t read all [fol. 33] of them.

- Q. I don’t imagine the librarian has. If the standards of the Association of American Law Schools are higher or more stringent than those of the American Bar Association, as you stated, as a member of the board, how could a student be said to be offered equal educational facilities in the basement across the street as he would at the University of Texas, assuming that the Association of American Law Schools requires a minimum of four full time teachers, irrespective of the number of students?

- Mr. Daniel: We object to that question as argument; presuming the requirement of the American Association of Law Schools there, and for the same reason they objected to the requirements of the American Bar Association, we object to that question.

- The Court: I think he can answer it.

- A. It is a little involved. Break it down, if you can.

- By Mr. Marshall:

- Q. You stated before the requirements of the Association of American Law Schools were obviously more stringent?

- A. I said they were slightly different. They require ten thousand, and the American Bar, seventy-five hundred. In the average case that has no meaning. The student won’t study over 200 books in his courses.

- Q. Have you ever taught school? [fol. 34]

- A. I have lectured a few times.

- Q. But you have never been a full time professor?

- A. No, that is correct. I have been a practicing attorney.

- Q. You have been a practicing lawyer?

- A. Twenty-seven years.

- Q. Are you familiar with the teaching curriculum now used in law schools?

- A. Somewhat.

- Q. Are you familiar with the teaching methods now, for instance, the case book, and the old outline method?

- A. Yes, sir. The case book gives more stress to the work done by the student himself in reading, instead of the[19]professor reading and the student making notes, like he used to do twenty-five years ago.

- Q. And he takes the case book—

- A. And studies it himself.

- Q. And he goes up in the library and reads the footnotes?

- A. Yes, sir; and the law reviews.

- Q. Incidentally, how many law reviews did you see in this library over here?

- A. In the—

- Q. At the Capitol?

- A. I couldn’t say. I have gone through a good many of them when I was in the Attorney General’s Office.

- Q. I am talking about today.[fol. 35]

- A. I didn’t see them. I am sure they are there.

- Q. You don’t know how many are there now?

- A. No.

- Q. Assuming the requirements of the Association of American Law Schools are more strict than those of the American Bar Association, and the University of Texas is a member of both, I think we can assume that is a fact. The Association of American Law Schools requires a minimum of four full time professors, irrespective of the number of students. Would you say a student at that school would get equal educational opportunity with the University of Texas?

- A. I didn’t qualify as an expert on law schools, and I, perhaps, as a practicing lawyer, do not lay as much stress on having as many full time law professors as most people. I think an occasional practicing lawyer mixed up in the faculty is a fine thing. The fact that the American Association of Law Schools wants more full time professors than the American Bar Association doesn’t change my view. What we are talking about, affording the opportunity to a student, assisted by a preceptor who knows some law, can learn the principles of law and certainly one student, or ten, or twenty-five, assisted by four preceptors in law would have a better opportunity, if he has it within himself to develop, than one who was asked an occasional question every thirty days or so.

- Q. The important thing is that if this proposed school used [fol. 36] in the first hypothetical question did not, and could not under those facts, meet the requirements of the Association of American Law Schools, and the University of Texas[20]does meet them; would you say that that is giving equal facilities?

- A. It wouldn’t have the slightest effect on the student, whether he was a trained lawyer when he left the school or not.

- Q. Would that be equal?

- A. Equal facilities for what? For him to acquire a legal education?

- Q. No, sir.

- A. Whether they were a member of the Association would be utterly immaterial.

- Q. The question would be whether that would be facilities equal to the facilities at the University of Texas.

- A. If you are talking about physical facilities—

- Q. I am talking about the whole law school—both. Would you say that that law school that you saw today, even with the opportunity to use the Capitol library, afforded facilities equal to that that you have seen repeatedly at the University of Texas?

- A. To one student?

- Q. No, not limited to one student for this question. You may go back to one student next time.

- A. Someone once said that Mark Hopkins, long-time pro-[fol. 37] fessor at Williams College, sat on the end of a log and taught a student on the other end of the log. It depends on the student and instructor, and what they are talking about. Whether they belong to an association or have complied with the standards, in my opinion, for this purpose, is utterly immaterial. If you have competent instructors with adequate books to teach that student, he can get his legal education.

- Q. Mr. Simmons, let’s start with—

- A. I couldn’t see how he could fail to get that if there were one or ten, where he couldn’t get a better education than any ten you would get in the other school, because half of them, I regret to say, look out the window. It gets humid, as it is here in the court room, and he would get a little sleepy, and he looks out the window, and he couldn’t do that if there were one or ten.

- Q. Are you opposed to large law schools?

- A. I am not advocating them. I am not impressed much by numbers, Mr. Marshall.

- Q. Since you say we get equal facilities, in your opinion—[21]

- A. I didn’t say that. I said he had an equal opportunity to get a legal education, is what I said.

- Q. Could he get an equal opportunity to get a legal education in a law office?

- A. I think so. The finest lawyers I have ever known, that picture of that one over there, for instance (referring to [fol. 38] photograph hanging in court room.)

- Q. Mr. Simmons, if we can stay on the facilities—

- A. All right.

- Q. The best way to get on it is to take the concrete ones. In your mind, is there any comparison in value of the building where the University of Texas Law School is with the building across the street where the Negro school is supposed to be?

- A. I think both of them could well be improved. The Texas Bar Association has been trying for years to get them to tear down the one at the University and build an adequate one.

- Q. What do you mean by “adequate?”

- A. For the number of students. It was built in 1907.

- Q. Is the one across the street equal in monetary value?

- A. Certainly not.

- Q. Certainly not. Approximately how many professors do they have at the University of Texas Law School?

- A. I don’t know. The school has changed from fifty year before last to eight hundred and something now. I couldn’t tell you.

- Q. Is the library at the University of Texas Law School larger than the library at the Capitol, and the one in the Negro law school together?

- A. Each one of them have, in my judgment, fifty thousand volumes, approximately. I don’t know how many more. [fol. 39]

- Q. Fifty thousand in that law school over there?

- A. At the Supreme Court approximately, I say.

- Q. Approximately how many in the basement of that building?

- A. I couldn’t say. The Texas University Law School—

- Q. No, the Negro law school?

- A. They had about 200 books, I would say.

- Q. What kind of books?

- A. They seemed to have some books on torts and contracts and legal bibliography and Texas Law Review, and a few miscellaneous books of that character. They didn’t[22]have any books that I saw, on equity, or on courses that you would give to post-graduates or seniors. These seemed to be, as far as these books were concerned, they seemed to be limited strictly to beginners.

- Q. Did you see the American Digest there?

- A. In this ground floor of the Colored Law School Building?

- Q. Yes.

- A. No, they were not there.

- Q. The United States Supreme Court Reports?

- A. They were not there.

- Q. Any state reports?

- A. They were not there.

- Q. There were no reports there?

- A. No.

- Q. There were some case books and text books? [fol. 40]

- A. Yes, and the Law Review. It was The Texas Law Review. I suppose they are partial to that one.

- Q. Is that the only one?

- A. That is all I saw. I wouldn’t say the only one.

- Q. Do you know the type of books required in an approved law school to be used in the first year courses?

- A. These same books on torts, contracts and legal bibliography are the same ones used at the University of Texas.

- Q. Don’t they teach legal bibliography in the library, and use all of the books in the library?

- A. That is where you learn it.

- Q. Do you not teach legal bibliography in the library?

- A. I couldn’t answer that. Not when I went to school. They taught it in the class rooms.

- Q. We are comparing these facilities as of today.

- A. I have outlined at some length what I saw, and in my opinion, if a man wants to become a lawyer, so far as the books, the curriculum, and the professors are concerned, he can become a lawyer with what is offered him here. Some people want a big law library and a big school. I happen to have studied in night school and a law office, and this school. Perhaps I am not as impressed with a big school as some other people.

- Q. I understand, but as one point in this case, the State makes an allegation that they are affording equal educational facilities, not equal opportunity to learn, necessarily. [fol. 41]

- A. All I understood was that the State was re-[23]quired to furnish substantially equal facilities and opportunity to acquire a legal education. I am not arguing the law. I am not a lawyer in this case. I was just passing through the city. By reason of having been president of the lawyers from Houston to the United States, they asked me to talk about the standards. If you want me to argue about whether these facilities are worth as much as something else, you had better get somebody else.

- Q. Hasn’t the American Bar Association taken a specific stand urging the abolishment of all law schools not set up as parts of universities?

- A. Well, they have taken a stand that they do not in general approve what they call the commercial law schools. I recall no resolution saying that they must be part of a university.

- Q. You set all of the standards or ultimate goals?

- A. They are recommendations.

- Q. Didn’t the American Bar Association cooperate with the Dallas Bar Association in taking all of the small law schools in Dallas and centering them at Southern Methodist University, the American Bar Association?

- A. Some of our men, I am sure, helped with that. The schools there were commercial schools, the night schools, as I recall. I might add there is some movement on foot to do the same thing in Houston. [fol. 42]

- Q. Go right ahead.

- A. I have been asked by the President of the University of Houston if I won’t discuss with them means by which they could take over one or two night schools in Houston, and those are commercial schools. The Houston Law School is a night school which I attended back thirty years ago. I would be very happy to see them a part of a university, personally.

- Q. Do you know what hours the Capitol Library is open?

- A. Not right now. I studied there many times, day and night.

- Q. Do you know the hours?

- A. I do not know.

- Q. That is all.[24]

- Redirect examination. Questions by Mr. Daniel:

- Q. Mr. Simmons, the two smaller law schools that you mentioned which are recognized by the American Bar Association and the American Association of Law Schools, Howard University and Lincoln University, are they separate Negro law schools?

- A. That is my understanding.

- Q. As to the facilities, in your opinion, are the three class rooms that you have inspected, for the Negro law school, based on from one to ten students, equal as far as the opportunities for study and class room work are concerned, with three class rooms at the University of Texas for 850 students?

- A. Well, we have seats, and the professor could do very [fol. 43] nicely here teaching ten or fifteen students. He certainly, I think, could get more into their heads than sitting with 300, and in the back row.

- Q. Referring back to the question asked on cross examination as to whether you knew of any accredited law school that had its law library in a separate building, are you acquainted with the University of Michigan Law School?

- A. I have been there many times.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the location of the library building?

- A. It is in the same quadrangle. It is in the W. W. Cook Library Building, across the quadrangle from the Law School. As a matter of fact, I at one time had an office in Hutchens Hall, a part of that building. Hutchens is President of the American Judicature Society.

- Q. That is all.

- Recross examination.

- Questions by Mr. Marshall:

- Q. Isn’t there a connecting alcove between the Law Library and the Law School at the University of Michigan?

- A. It is a large school, and it is a beautiful quadrangle of buildings. Hutchens Hall and W. W. Cook Library are very close.

- Q. The same is true at Yale?

- A. I am not so familiar there.[25][fol. 44]

- Q. When you say Howard University is a Negro University or school, do you know that of your own knowledge?

- A. All I say is that it was accredited as a colored law school.

- Q. Do you know whether or not there are any other students prevented from attending there?

- A. I don’t know anything about it. All I know is that in the accredited law schools, Lincoln and Howard are listed as colored law schools.

- Q. That is in the American Bar Association listing?

- A. That is what I was being asked about. Would you like to see that?

- Q. No. I was there when it was accredited. How long will it be, assuming your hypothetical school here,—I mean, involved in the hypothetical question—

- A. Don’t say my hypothetical school.

- Q. I withdraw that. That school that you went in today over here across the street?

- A. I don’t think anything is a school until it has got some students. The building where I was today?

- Q. That the building, if it should be opened as a school, how long would it have to operate before the American Bar Association would be in a position to accredit it?

- A. I think preferably it ought to wait and operate long enough to see if the student body was seriously interested in studying law, or if they had some other purpose, and then if [fol. 45] it complied with the standards, it would be given a provisional approval.

- Q. Can we stop there and see about how long that would be?

- A. I can’t say. I have known of instances where, for instance, I believe St. John’s University in New York, Brooklyn, was kept on provisional approval for two years; and I believe the University of Georgia Law School was put on provisional approval when it had some difficulty with a gentleman named Talbot.

- Q. How long after the provisional approval until you get it on the entire approval?

- A. I would say two years.

- Q. That is all. Mr. Daniel: That is all.

- (Witness excused.)[26]

- Mr. Daniel: I would like to make a statement as to the order of our evidence, now that we have Mr. Simmons excused. You will excuse him?

- Mr. Marshall: Certainly.

- Mr. Daniel: We first wish to offer the—call the attention of the Court to Senate Bill 228, which authorized A. & M. College to set up a law school at Prairie View, and then to offer the resolution on that college, authorizing the establishment of it, and a deposition showing what was done [fol. 46] under the bill, in order that the record might be complete, since the filing of this suit, as to how the State has attempted to meet its obligation; and then we will go into the new school here in Austin.

- At this time we offer the resolution of the Board of Directors of A. & M. College, dated November 27, 1946.

- Mr. Durham: That is the same resolution that was introduced on the trial before.

- Said instrument was admitted in evidence as Respondents’ Exhibit No. 2.

- Mr. Daniel: We next wish to offer from the deposition of E. L. Angell the agreement of counsel as to waiver of formalities in the taking of this deposition, and I will ask Mr. Littleton if he will read the direct answers. I will propound the questions that were submitted by the State, by the Respondents, to Mr. Angell.

- The following agreement of counsel ordered copied into the record at this point.

- In the 126th District Court of Travis County, Texas No. 74,945 Heman Marion Sweatt vs.

- Theophilis Shickel Painter, Charles Tilford McCormick, Edward Jackson Mathews: Board of Regents, Dudley K. [fol. 47] Woodward, Jr., E. E. Kirkpatrick, W. Scott Schreiner, G. 0. Terrell, Edward B. Tucker, David M. Warren, William E. Darden, Mrs. Margaret Batts Tobin, and James W. Rockwell

- The parties to the above entitled and numbered cause, through their attorneys of record, agree that the deposition[27]of Respondents’ witness, E. L. Angell, who resides at Bryan, Brazos County, Texas, may be taken without the filing with the clerk of said court of notice of intention to apply for commission to take the answers of such witness to interrogatories attached to such notice, or service of copy thereof, and of the attached interrogatories, or five days’ time before issuance of commission, as otherwise required by law, and further agree that a commission to take such deposition shall be issued by such clerk immediately, and that such deposition shall be taken as provided by law in accordance with such commission and the attached direct and cross interrogatories by any officer authorized thereto by law at any place where the witness may be found and returned in the statutory manner for use as evidence in the trial of such cause, and further agree that when such deposition is returned it may be so used, subject to all other legal objections, at the trial of such cause. Price Daniel, Attorney General of Texas, by (s.) [fol. 48] Jackson Littleton, Assistant Attorney General, Attorneys for Respondents. By (s.) W. J. Durham, Attorney for Relator.

- The following was read into the record, Mr. Daniel reading the Direct Interrogatories, and Mr. Littleton reading the answers, from Deposition of E. L. Angell.

- E. L. Angell, (Deposition.)

- Direct Interrogatories to be propounded to E. L. Angell, Secretary of the Board of Directors of the Agricultural and Mechanical College, a witness for Respondents in the above entitled and numbered cause, for the taking of his deposition:

- Q. 1. What is your name?

- A. 1. E. L. Angell.

- Q. 2. Where do you live?

- A. 2. College Station, Texas.

- Q. 3. What is your position or employment?

- A. 3. Assistant to the President of the A. & M. College and Secretary to the Board of Directors. [fol. 49] Q. 4. How long have you held such position?

- A. 4. Assistant to the President since June of 1941, with the exception of about two years in the Army. Secretary to the Board since January of 1946.[28]

- Q. 5. State whether you are the same E. L. Angell who testified in a hearing of the case, Sweatt v. Painter, on December 17,1946.

- A. 5. I am.

- Q. 6. State whether you are familiar with the provisions of a resolution adopted by the Board of Directors of the Agricultural and Mechanical College on the 27th day of November, 1946, being Minute Order No. 203-46, and entitled The Establishment of Law Course for Negro Students.

- A. 6. I am.

- Q. 7. State if you are the same E. L. Angell who certified to said resolution by testimony in the hearing of the case of Sweatt v. Painter on December 17, 1946.

- A. 7. I am.

- Q. 8. State who, if anyone, was assigned the responsibility of carrying out the purpose of the resolution.

- Mr. Durham: Just a minute. We object to that answer for the reason that the resolution would be the best evidence of its contents. The resolution is in evidence before this Court.

- The Court: I think that is true. [fol. 50]

- Q. 9. State what, within your knowledge, was done to carry out the provisions of said resolution.

- Mr. Durham: Your Honor, we want to ask that, until I make my objection, Mr. Littleton be asked to stop at the word “renovated.”

- Mr. Littleton: Do you mean as to all of the other paragraphs?

- Mr. Durham: We have no objection to any portion of it down to there.

- Counsel and the Court conferred off the record regarding said answer.

- Mr. Daniel: Just read it to the Reporter, and let him get exactly what you say.

- A. 9. A suite of rooms in an office building at 409 1/2 Milam Street, Houston, Texas, was secured. These rooms were completely renovated. This suite of rooms was furnished with new furnishings purchased for that purpose. The services of Attorney William G. Dickson were secured as a teacher for the law courses. Immediately available were some 400 basic law reference books. A list of books required for first year law students[29]was furnished by the Dean of Law at the University of Texas. It was ascertained from a law book firm that these books could be delivered to Houston on 24 hours’ notice. [fol. 51] The immediate supervision was under the direction of the Principal of Prairie View University, Dr. E. B. Evans.

- Q. 10. State whether any building or housing facilities were acquired.

- A. 10. Yes; suite of offices at 409 1/2 Milam Street, Houston, Texas.

- Q. 11. If you have stated that building and housing facilities were acquired, state the location of such facilities, and describe them fully.

- A. 11. Suite of three rooms at 409 1/2 Milam Street, Houston, Texas, which was an office building.

- Q. 12. State whether anything was done to secure professors for the instruction of the law courses mentioned in the resolution.

- A. 12. William C. Dickson was employed.

- Q. 13. If you have stated that anything was done, then state what arrangements were made, and the names of individuals with whom they were made.

- A. 13. William C. Dickson was employed, to teach the law courses, the supervision of the establishment was under the direction of Dr. E. B. Evans, Principal of the Prairie View University.

- Q. 14. If you have stated that any instructors and professors for the law courses mentioned were secured, then [fol. 52] state the names of those secured and the qualifications of each.

- A. 14. William C. Dickson was employed to teach the law courses. He is a practicing attorney in Houston. His training includes Bachelor of Arts degree from Pomona College of California, the Bachelor of Law degree from Harvard University, and the Master of Law from Boston University. In case of need of an additional teacher Dickson’s partner, H. S. Davis, Jr., was available. He holds an A. B. degree from Morehouse College, Atlanta, Georgia, and a J. D. degree from Northwestern University.

- Q. 15. State whether any library facilities were obtained.

- A. 15. Yes, as stated in answer to Interrogatory No. 9.

- Q. 16. If you have stated that library facilities were obtained, then describe fully the kind of facilities secured.[30]

- A. 16. Yes, as stated in answer to Interrogatory No. 9.

- Q. 17. If you have stated that a law school or law courses were provided pursuant to the resolution of November 27, 1946, then state when they were provided.

- Mr. Durham: Your Honor, we object to that as not being responsive to the question asked. He asked him when it was established, and he said available. He doesn’t answer that question.

- [fol. 53] The Court: Yes, I think that is right.

- Mr. Daniel: All right, sir. We withdraw that Question 17.

- Q. 18. If you have stated that a law school or law courses were provided, then state whether such school or courses were open for registration to qualified applicants.

- Mr. Durham: Your Honor, we object to that answer for •the reason the answer is “the law course was available.” He gives no dates or time, and it is not responsive to that question. It isn’t even intelligible.

- The Court: It doesn’t seem to be responsive, or even helpful.

- Mr. Daniel: Your Honor, it says whether or not it was open for registration of qualified applicants. I don’t know if the fact that it was available— The Court: He could have said yes or no. Mr. Daniel: Yes, he could.

- Q. 19. If you have stated that such school or courses were open for registration to qualified applicants, then state the dates that such registration was opened and closed.

- A. 19. It was opened on the 1st of February, 1947, and closed on the 14th day of February, 1947,—

- Mr. Durham: Follow it on out; “* * * which was four [fol. 54] days longer * * *—

- The Court: That portion of it isn’t; responsive.

- Q. 20. If you have stated that registration for a law school or law courses was opened and have given the dates, then state whether during such period any applications for registration were made.

- A. 20. No qualified applicants applied.

- Mr. Daniel: That is all we wish to offer until we see what you are going to offer on cross. [31]

- The Court: You spoke about some stipulations you will work out. Perhaps you will be able to work out something on that.

- Mr. Durham: We don’t intend to offer the crosses at this .me.

- Mr. Daniel: We wish to offer some of them, then. From : the deposition of Mr. Angell we wish to offer the following questions and answers from Gross Interrogatories propounded by Relator.

- Mr. Daniel read Cross Interrogatories, and Mr. Littleton lead answers, from Deposition of E. L. Angell, as follows:

- Q. 1. By what authority was a Law School for Negroes in Houston set up?

- Mr. Durham: When he gets down to the word “and” I ‘want to object to it. The resolution is the best evidence. fol. 55] The Court: That is right. Mr. Daniel: You are asking him for it at this time. The Court: I believe he can state the law, and the resolution. The resolution is in.

- A. 1. The law course for Negroes was established under authority of Senate Bill No. 228 of the 49th Legislature, and a Resolution of the Board of Directors of the A. & M. College of November 27,1946.

- Q. 2. What action, if any, did Prairie View University make in accordance with said resolutions in setting up a Law School for Negroes in Houston?

- A. 2. The Principal of Prairie View University, Dr. E. B. Evans, was charged with details of setting up the law course.

- Q. 3. How much money was expended in setting up this Law School for Negroes in Houston?

- A. 3. I do not know.

- Q. 4. Were books, equipment and supplies for this Law School for Negroes in Houston purchased for cash or by State requisition or vouchers?

- A. 4. They were purchased by Prairie View University, using their funds.

- Q. 26. What salary agreement was made with each teacher If the agreement was written, attach a copy of the [fol. 56] same to this deposition.

- A. 26. Dickson was to be paid at the rate of $5,000.00 per year. The agreement was made by Dr. E. B. Evans of[32]Prairie View University and I do not have a copy of the agreement.

- Q. 27. What salary was paid each of these teachers’

- A. 27. He was paid at the rate of $5,000.00 per year.

- Q. 29. How much time was each. teacher required to give to the work of the Law School, that is, state whether they teachers were to give part time or full time and if pa time, exactly how many hours per day, per week.

- A. 29. Full time if necessary.

- Q. 41. When was this library purchased and what was its purchase price?

- Mr. Durham: We want to object to that word ‘ ‘ available He asked him what he purchased, and it is not responsive” The Court: Let me read it.

- Mr. Durham: We object to the entire part of it after leave the word “made”, —”Some 400 basic reference books were made.

- The Court: Let him put the question again.

- (Mr. Daniel read Question 41 as set out above.) The Court: I don’t believe that is responsive.

- Q. 42. How many library stacks or book cases were re-[fol. 57] quired, and what kind?

- Mr. Durham: We object to that as not being response The Court: It is not responsive.

- Q. 45. Give the name and qualifications and salary each of these officers of the Law School for Negroes Houston: (a) Dean (b) Registrar (c) Librarian.

- Mr. Durham: We object to that for the reason the answer’ is not responsive.

- The Court: He doesn’t appear to answer it at all. I give you your bill on it.

- Mr. Durham: Is that No. 45, Your Honor?

- The Court: Yes, I am giving you your point on that.

- Mr. Durham: We object to that for the reason it is responsive. He doesn’t name anybody.

- The Court: I think perhaps if you will break it up a little it might be responsive. He might say the dean and registrar[33]were officials of Prairie View University. It is going to be difficult to understand. I will give your point on it.

- A. 45. The Dean and Registrar were officials of Prairie View University and Prairie View University was to furnish [fol. 58] librarian services at the Houston establishment.

- Q. 49. State what courses of instruction were offered in the Law School for Negroes in Houston in detail, as follows:

- (a) Name of course. (b) Case book and text book used. (c) Hours per week classes scheduled to meet. (d) Time of day each class scheduled to meet and the number of the room in which it was to meet. (e) The number of semester or quarter hours credit to be given for each course.

- Mr. Durham: We object to that as being a conclusion of the witness.

- The Court: And it isn’t responsive either. Mr. Durham: And it isn’t responsive.

- Q. 53. Did the faculty of the School of Law for Negroes in Houston prepare the curriculum, schedule the classes and otherwise conduct the general educational work of the law school? Mr. Durham: We object to that. It isn’t responsive.

- The Court: I think it isn’t responsive.

- Q. 58. Is this Law School for Negroes still in existence in Houston?

- Mr. Durham: We object to that. That isn’t responsive. The Court: The first sentence ends it; yes.

- [fol. 59] Mr. Durham: The first sentence.

- A. 58. The facilities were rented until the 1st of March.

- Mr. Daniel: All right, that is all. We wish to call the attention of the Court to Senate Bill No. 140 of the 50th Legislature, and briefly to review that before we put on the evidence that follows that.

- The Court: I think we will take that up in the morning. 3—725 [34]

- (Court was recessed at 4: 30 p. m., May 12, 1947, until 9: 00 a. m., May 13, 1947.)

- Morning Session. May 13,1947. 9: 00 a. m.

- Mr. Daniel: May it please the Court, I would like to call attention of the Court to Senate Bill No. 140 of the 50th Legislature, which became effective March 3, 1947. Rather than read the sections that have to do with the establishment of the State University for Negroes in Houston, Texas, I will go over those paragraphs and summarize them, if that is all right with the Court.

- (Counsel at this point summarized portions of said bill.) [fol. 60] I would like to call Mr. D. K. Woodward.

- D. K. Woodward, Jr., a witness produced by the Respondents, having been by the Court first duly sworn as a witness, testified as follows:

- Direct examination.

- Questions by Mr. Daniel:

- Q. State your name, please, sir.

- A. D. K. Woodward, Jr.

- Q. Where do you live, Mr. Woodward?

- A. Dallas, Texas.

- Q. And what is your business?

- A. I am a lawyer.

- Q. What, if any, official capacity do you have with the University of Texas?

- A. I am a member of the Board of Regents, and Chairman of that Board.

- Q. How long have you been Chairman of the Board of Regents of the University of Texas?

- A. Since the end of November, 1944.

- Q. Have you, since becoming Chairman of the Board of

- Regents of the University of Texas, acquainted yourself with the matter of education for Negroes in Texas? [35]

- A. To the best of my ability, yes, sir.

- Q. Are you acquainted with Senate Bill No. 140, which [fol. 61] I have just outlined to the Court?

- A. Yes, sir, I am.

- Q. I will ask you if you had anything to do with the preparation of the bill, and especially the part that the University of Texas—as relates to the University of Texas?

- Mr. Durham: We object to it unless he shows he is a member of the Legislature.

- The Court: I think that would be correct.

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. Were you acquainted with the terms embodied in that bill before they were actually enacted by the Legislature?

- A. I was.

- Q. Have you studied the terms of this bill, when the bill was pending in the Legislature, and before final passage of it?

- Mr. Durham: We object to that as being immaterial. The Court: I think it is immaterial what he did about it. Mr. Daniel: Your Honor, we are simply leading up to show the University Board met in anticipation of the final passage of this law, and began their actions a few days before the law became effective. The Court: He can tell what his Board did. Mr. Durham: We don’t think that anything that a citizen did would be construed, or the Court could presume it would influence the Legislature. I think that would be a [fol. 62] reflection upon the Legislature. The Court: I sustain the objection.

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. Did that Board have a meeting prior to the time that this bill was finally passed by the Legislature?

- A. Yes, the Board met the 28th of February.

- Q. 1947?

- A. Yes.

- Q. Had the Senate Bill 140 already passed one branch of the Legislature?

- A. Two branches, both.

- Q. Both branches? [36]

- A. It had passed in the Senate on the 24th, the House on the 27th, with certain amendments, and it was in that state that the bill was laid before the Board at its meeting on the 28th of February.

- Q. Did you as Chairman lay the bill before the Board”

- A. I did.

- Q. Did the Board of Regents of the University of Texas on the 28th of February study the requirements made of you by the bill?

- A. Yes.

- Q. What, if anything,—did you pass any resolutions at that time?

- A. We did.

- Q. Do you have a copy of the resolutions? [fol. 63]

- A. I have.

- Q. Is this a true and correct copy of the resolution passed by the Board of Regents on the 28th of February?

- A. It is.

- Q. We wish to offer it.

- (Said instrument was admitted in. evidence as Respondents’ Exhibit No. 3.)

- Q. Now, Mr. Woodward, in accordance with that resolution, I will ask you whether or not you proceeded to establish the separate law school therein called for?

- A. We did.

- Q. Where was it established? –

- A. On East 13th Street, in the City of Austin, immediately adjoining the Capitol grounds on the north. I think the’ number is 104 East 13th.

- Q. What kind of building do you have there, as far a classrooms are concerned? How many classrooms do you have in the building where the law school is located?

- A. Presently available we have four buildings—four rooms, three of moderate size, and a fourth, small room for a reception room, and the small toilet facilities.

- Q. Did you, in accordance with that resolution, give certain instructions to Dean McCormick, Dean of the University School of Law?

- A. I did. [fol. 64]

- Q. Will you state to the Court what instruction you gave him as to his part in this school?

- A. I requested through the Dean of the entire person- of the Law School an expression as to their willingness[37]or not to teach in the proposed new law school. It was reported to me that they were unanimous—

- Mr. Durham: We object to that.

- The Court: Yes. That would be hearsay. We will sustain the objection to whatever was reported to him. He can testify to what he knows.

- A. All right. I had a conference—a number of conferences—with Dean McCormick concerning the establishment of the law school and requested him to give us the, provide the curriculum and the instructors called for in carrying out the resolution.

- Q. As to the location of the law school of the State University for Negroes, the building that you have spoken of, how far is that from the Capitol grounds?

- A. It is about a hundred yards from the north door of the Capitol.

- Q. You are talking now about the Capitol Building?

- A. Yes,—from the Capitol grounds?

- Q. Yes.

- A. I would say 20 feet. It is a very narrow street there, East 13th Street.

- [fol. 65]

- Q. Between the location of the law school and the Capitol grounds?

- A. Yes.

- Q. You mentioned something about another distance, as between the door of the separate law school and the State Capitol Building. If you know, how far is that?

- A. I would estimate it to be a hundred yards, 300 feet.

- Q. Where is the law school located with reference to the University of Texas?

- A. Well, the University of Texas lies north of 21st Street in the City of Austin, covers a considerable area out there. That would be eight blocks north of the new law school on 13th Street.

- Q. Then your new law school is located between the State Capitol Building and the University of Texas Campus?

- A. That would be right.

- Q. Where is—state how the new law school is located with reference to the business district of Austin; is it nearer the business district than the University of Texas Law School or not?

- A. Yes, sir; eight blocks nearer. [38]

- Q. Is your new law school nearer the banks of Austin and other business facilities than the University of Texas?

- A. It is eight blocks nearer.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the State Library called for in this bill, in the Capitol Building? [fol. 66]

- A. I am.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the location of that library?

- A. I am, the second floor of the Capitol Building, north wing.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the space therein, and desks, as to availability of the space and working room in that library for students?

- A. I am, and have been for many, many years. I have frequented it myself.

- Q. That is on the second floor of the Capitol Building?

- A. Yes.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the Texas University Library

- and the facilities thereof?

- A. No, I am not, not as closely as I should be. I know in a general way what it is.

- Q. Are you acquainted with the working room at the University of Texas Law School Library, not the books?

- A. I couldn’t say that I am with any degree of accuracy. I know they are sorely pressed for space.

- Mr. Durham: We object to that as not being responsive.

- The Court: Yes.

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. This resolution calls for the establishment of the same courses, a curriculum consisting of the same courses in law as those offered at the University of Texas?

- A. It does.

- Q. Did you or not give instructions to the Dean of the [fol. 67] University of Texas Law School to establish such a curriculum?

- A. I did.

- Q. The resolution also calls for the use of the same faculty members. I will ask you if you gave instructions in accordance with the resolution to the Dean of the University of Texas Law School with reference to the use of the University of Texas Law School faculty members?

- A. I did. [39]

- Q. Was the new law school placed in readiness for operations on March 10, as called for in the resolution?

- Mr. Durham: We object to that as a conclusion and opinion. The Court: He can say what was done.

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. Will you just state to the Court what was done with reference to having the school ready for registration, as far as you know?

- A. By March 10th?

- Q. Yes.

- A. The premises were put in order for it, cleaned up, painted, and the desks and chairs and certain law books placed in there, and an attendant placed in charge, and notices were sent as directed in the resolution to all persons interested, and there was considerable newspaper publicity given so that we did everything that—

- Mr. Durham: When be said he did everything— [fol. 68] The Court: Yes. He can say what he did.

- A. Yes. All of the actions called for in that resolution, to the best of our ability—

- By Mr. Daniel:

- Q. They were accomplished by March 10th, were they?

- A. That is correct.

- Q. The resolution authorizes you to purchase a permanent law library for the school which will meet the standards set by the American Association of Law Schools?

- A. Yes, sir.

- Q. I will ask you what you did in accordance with that provision of the resolution?

- A. I made requisition on the Board of Control of the State of Texas on March 1st, I think it was, either February 28th, or March 1st. The document itself would show the exact date, calling for bids at the earliest practicable date for a list of books purporting to be a complete list as called for by the American Association of Law Schools.

- Q. Who did you have prepare that list to meet the standards of the American Association of Law Schools?

- A. The Dean of the Law School of the University of Texas, Dean McCormick. [40]

- Q. The list that was prepared by him, or under his direction, then, was turned over to you?

- A. It was presented to me in the regular course for the [fol. 69] execution and delivery of a requisition on the State Board of Control, as required by law, for the purchase of public property.

- Q. Did you execute that requisition ?.

- A. I did, immediately on either the 28th of February or the 1st of March; executed that and filed it with the Board of Control.

- Q. I believe that is all.

- Cross-examination.

- Questions by Mr. Marshall:

- Q. Judge Woodward, as long as you have been a member< of the Board of Regents of the University of Texas, has it or has it not been the policy and custom of the University of Texas not to admit Negroes to any branch thereof?