Espionage Act, 18 U.S. Code Chapter 37 (1917)

The Espionage Act was the Congress response to a growing fear that public criticism of the war effort would make it difficult to conscript the needed manpower for American participation. Also contributing to widespread unease were the actions of labor groups who proclaimed their sympathy for laborers through the world, including those in Russia, the Espionage Act was passed in June 1917 and provided penalties of 20 years imprisonment and fines up to $10,000 for those convicted of interfering with military recruitment.

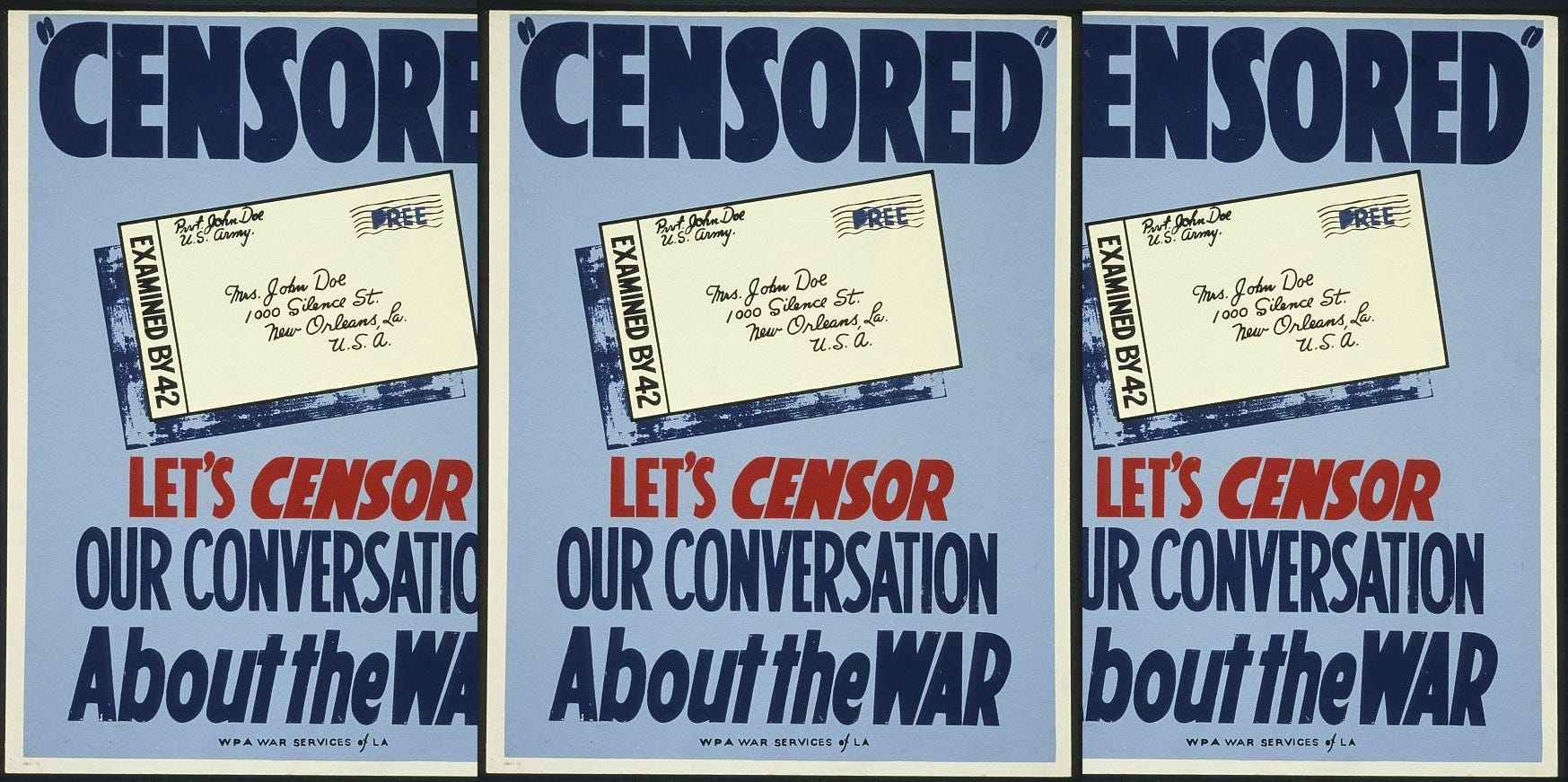

State and local Committees of Public Safety, although they often did effective work, also at times exceeded legitimate object and left a memory of unjust repression in some communities. No formal censorship existed but the result was the same, through pressure and the mere threat of prosecution under the Espionage Act of 1917.

Speech to the Court (excerpts), Eugene V. Debs (1918)

The man who was “too good for this world”, Eugene Debs was a prominent leader of socialist movement. The best-known apostle of industrial unionism in the early years of the 20th century, Debs ran for president of the United States for the Socialist Party five times between 1900 and 1920, winning millions of votes. Although none of his dreams were realized during his lifetime, Debs inspired millions to believe in “the emancipation of the working class and the brotherhood of all mankind,” and he helped spur the rise of industrial unionism and the adoption of progressive social and economic reforms. Lofty speaker, he was arrested in 1918 under the Sedition Act because of his anti-war speeches.

Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

I listened to all that was said in this court in support and justification of this prosecution, but my mind remains unchanged. I look upon the Espionage Law as a despotic enactment in flagrant conflict with democratic principles and with the spirit of free institutions…

Your Honor, I have stated in this court that I am opposed to the social system in which we live; that I believe in a fundamental change—but if possible by peaceable and orderly means…

Standing here this morning, I recall my boyhood. At fourteen I went to work in a railroad shop; at sixteen I was firing a freight engine on a railroad. I remember all the hardships and privations of that earlier day, and from that time until now my heart has been with the working class. I could have been in Congress long ago. I have preferred to go to prison…

I am thinking this morning of the men in the mills and the factories; of the men in the mines and on the railroads. I am thinking of the women who for a paltry wage are compelled to work out their barren lives; of the little children who in this system are robbed of their childhood and in their tender years are seized in the remorseless grasp of Mammon and forced into the industrial dungeons, there to feed the monster machines while they themselves are being starved and stunted, body and soul. I see them dwarfed and diseased and their little lives broken and blasted because in this high noon of Christian civilization money is still so much more important than the flesh and blood of childhood. In very truth gold is god today and rules with pitiless sway in the affairs of men.

In this country—the most favored beneath the bending skies—we have vast areas of the richest and most fertile soil, material resources in inexhaustible abundance, the most marvelous productive machinery on earth, and millions of eager workers ready to apply their labor to that machinery to produce in abundance for every man, woman, and child—and if there are still vast numbers of our people who are the victims of poverty and whose lives are an unceasing struggle all the way from youth to old age, until at last death comes to their rescue and lulls these hapless victims to dreamless sleep, it is not the fault of the Almighty: it cannot be charged to nature, but it is due entirely to the outgrown social system in which we live that ought to be abolished not only in the interest of the toiling masses but in the higher interest of all humanity…

I believe, Your Honor, in common with all Socialists, that this nation ought to own and control its own industries. I believe, as all Socialists do, that all things that are jointly needed and used ought to be jointly owned—that industry, the basis of our social life, instead of being the private property of a few and operated for their enrichment, ought to be the common property of all, democratically administered in the interest of all…

I am opposing a social order in which it is possible for one man who does absolutely nothing that is useful to amass a fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars, while millions of men and women who work all the days of their lives secure barely enough for a wretched existence.

This order of things cannot always endure. I have registered my protest against it. I recognize the feebleness of my effort, but, fortunately, I am not alone. There are multiplied thousands of others who, like myself, have come to realize that before we may truly enjoy the blessings of civilized life, we must reorganize society upon a mutual and cooperative basis; and to this end we have organized a great economic and political movement that spreads over the face of all the earth.

There are today upwards of sixty millions of Socialists, loyal, devoted adherents to this cause, regardless of nationality, race, creed, color, or sex. They are all making common cause. They are spreading with tireless energy the propaganda of the new social order. They are waiting, watching, and working hopefully through all the hours of the day and the night. They are still in a minority. But they have learned how to be patient and to bide their time. The feel—they know, indeed—that the time is coming, in spite of all opposition, all persecution, when this emancipating gospel will spread among all the peoples, and when this minority will become the triumphant majority and, sweeping into power, inaugurate the greates social and economic change in history.

In that day we shall have the universal commonwealth—the harmonious cooperation of every nation with every other nation on earth…

Your Honor, I ask no mercy and I plead for no immunity. I realize that finally the right must prevail. I never so clearly comprehended as now the great struggle between the powers of greed and exploitation on the one hand and upon the other the rising hosts of industrial freedom and social justice.

I can see the dawn of the better day for humanity. The people are awakening. In due time they will and must come to their own.

When the mariner, sailing over tropic seas, looks for relief from his weary watch, he turns his eyes toward the southern cross, burning luridly above the tempest-vexed ocean. As the midnight approaches, the southern cross begins to bend, the whirling worlds change their places, and with starry finger-points the Almighty marks the passage of time upon the dial of the universe, and though no bell may beat the glad tidings, the lookout knows that the midnight is passing and that relief and rest are close at hand. Let the people everywhere take heart of hope, for the cross is bending, the midnight is passing, and joy comet with the morning.

Mayflower Photoplay Company, “Bolshevism on Trial” (1919)

As World War I was ending an anti-communist movement known as the First Red Scare began to spread across the United States of America. In 1917 Russia had undergone the Bolshevik Revolution. For some Americans communism was also, in theory, an expansionist ideology spread through revolution. Once the United States no longer had to concentrate its efforts on winning World War I, many Americans became afraid that communism might spread to the United States and threaten the nation’s “democratic” values. Fueling this fear was the mass immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans to the United States as well as labor unrest in the late 1910s, including the Great Steel Strike of 1919. Both the federal government and state governments reacted to that fear by attacking potential communist threats. The overt patriotism helped to fuel the Red Scare and the federal government’s fervor in rooting out communists led to major violations of civil liberties.