December 8, 1941: Address to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Address to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War, December 8, 1941,” UVA: Miller Center via the National Archives, 2019.

This speech, given to Congress by President Franklin Roosevelt on December 8, 1941, was given for the purpose of asking for a formal declaration of war against the Japanese Empire in retaliation for the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, an American naval base in Hawaii, just a day earlier. In support of his request, President Roosevelt cites Japan’s planned attack and additional Japanese attacks on locations in the Pacific. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been preparing the U.S. for war for years through a series of executive orders but had not asked Congress for a declaration of war knowing that he did not have the support [1]. By referencing in details the attack still fresh in the minds of not only Congress but the American people as well, Roosevelt makes his case for the United States’ entering the war that much stronger, in a sense invoking a rally-’round-the-flag effect. The speech was designed to persuade members of Congress to grant FDR’s want of a declaration of war. FDR’ speech is historically significant in that it is the last time a president has ever asked for and received a declaration of war. Presidents who have assumed the office after Roosevelt have often made war but have done so without the formal consent of Congress through a declaration. A president’s ability to make war without the approval of Congress has led to an increase in presidential powers in relation to war.

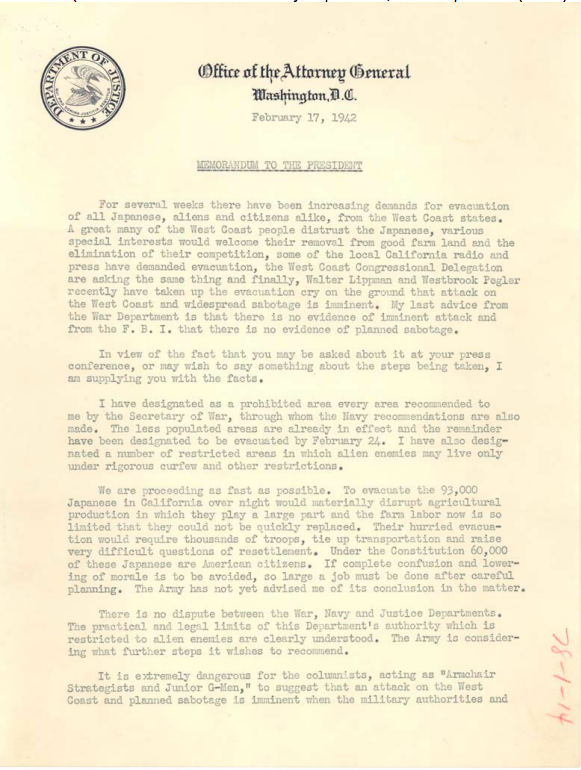

Memorandum to the President from Attorney General Francis Biddle. February 17, 1942.

Francis Biddle. “Memorandum to the President from Attorney General Francis Biddle, February 17,1942,” FDR Presidential Library and Museum

This memorandum, written by the Attorney General Francis Biddle to President Franklin Roosevelt was written for the purpose of warning the President to not give in to the pressures of the military and the public who were calling for mass internment of Japanese-Americans on the west coast. The memorandum is the Attorney General’s last attempt to steer the president away from evacuating and interning Japanese-Americans- something that was being proposed by the military and was widely supported. Biddle’s words offer a different viewpoint than that of the many who supported who supported the internment. Military members and non-Japanese-Americans who lived in California during World War II, pressured FDR to the point of him issuing Executive Order 9066 just two days after receiving the correspondence from the Attorney General, clearly showing his blatant disregard for the warnings posed by the Attorney General. This Executive Order expanded presidential war powers by allowing for the president to grant the military authority to evacuate Japanese-Americans from the western coast and intern them in camps.

Executive Order 9066 in Practice, 1942

Clem Albers. “Japanese-Americans transferring from train to bus at Lone Pine, California, bound for war relocation authority center at Manzanar, 1942” U.S. War Relocation Authority.

This picture was taken by the U.S. Relocation Authority, a United States’ government agency established to handle and document the internment in 1942 as a group of Japanese-Americans boarded a bus after departing from their train. It depicts a few of the 120,000 Japanese-American men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry whose lives were completely uprooted after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The government gave those affected by the EO only days to gather what they could carry and figure out what to do with the things they could not before mass internment of those living on the west coast with Japanese ancestry began [2]. Because of the widespread fear of potential sabotage and espionage by these Japanese-Americans, FDR, without the authority of Congress, was able to hold them with no charges and with no possibility of repeal. Regardless of the lack of formal congressional approval, when several Japanese-Americans challenged the government’s actions in court cases, the Supreme Court upheld their legality. This increased the possible measures that presidents, by their own authority, could take on the home front during wartime.

Notes

- Mathew A. Crenson and Benjamin Ginsberg Presidential Power: Unchecked and Unbalanced (New York: W.W. Norton, 2008), 225.

- NPR Japanese-Americans at Manzanar (California: National Park Service: U.S. Department of the Interior, 2015).