Below are links to natural urbanatural roosting sites, those places where the nonhuman world has incorporated cultural–or urban–links into their primarily wild, or nonhuman, settings. Have a look in order to appreciate the ways that the concept of urbanatural roosting goes both ways, from nature to cities and back again.

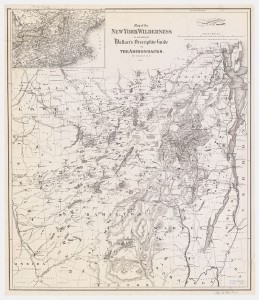

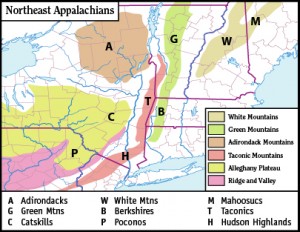

The Adirondacks

Artificial Reefs

Several of our examples of urbanatural roosting so far have discussed “nature” incorporated into the “urban.” However, urbanatural roosting can also be observed in the opposite way as well, by bringing the “urban” into the “natural.” One fascinating example of this is the case of artificial reefs. By sinking decommissioned subway cars, naval and commercial ships, as well as scrap industrial materials, it is possible for these underwater structures to imitate natural reefs. Realizing the productivity and benefits of these reefs, marine workers have begun intentionally sinking dilapidated rail cars, army tanks, and a wide range of ships–all the way up to aircraft carriers!–in locations where reef organisms can benefit from improved or alternative reef structures. Artificial reefs are becoming more popular among coastal towns, so that even a small state like Delaware has fourteen sites currently allowing for artificial reefs (dnrec). Like any natural reef, these artificial reefs attract organisms such as sponges early on, which then attract larger and larger species, and so on. In time, a fully established ecosystem forms around these “imposter” structures, making them almost indistinguishable from the real things, especially once the manmade materials become covered with animate and inanimate natural creations. What an innovative and intuitive way to utilize urban elements to enhance both natural ecosystems and the wider environment! –K.M.

Cape Cod

Located on the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, Cape Cod is the “extending arm” typically associated with the appearance of the state. Cape Cod includes several cities: Provincetown at the northern-most tip, Falmouth, and Chatham to the southeast, among others (Cape Cod Web). Close to Cape Cod are the two islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. The chain of land creates a horseshoe-shape surrounding Cape Cod Bay. Woods Hole is the southernmost city on Cape Cod and home to two major scientific institutions, the Marine Biological Laboratory and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (Woods Hole). The Marine Biological Laboratory, founded in 1888, is affiliated with the University of Chicago (MBL). The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, whose mission statement declares that it “is dedicated to research and education to advance understanding of the ocean and its interaction with the Earth system, and to communicating this understanding for the benefit of society” was established approximately forty years later, in 1930 (WHOI).

When one thinks of Cape Cod, thoughts of breathtaking scenery and boating over miles of New England waters come to mind. However, the real attraction of the northern tip of this gigantic peninsula (in addition to the shop-filled seaside streets of Provincetown), is an endless wall of parabolic sand dunes (parabolic, in this sense, simply meaning U-shaped). Years of erosion of the nearby scarps (steep slopes), the consistent presence of wind, and steady accumulations of sand, have all led to the growth and stability of these dramatic dunes (Guide’s Guide).

When one thinks of Cape Cod, thoughts of breathtaking scenery and boating over miles of New England waters come to mind. However, the real attraction of the northern tip of this gigantic peninsula (in addition to the shop-filled seaside streets of Provincetown), is an endless wall of parabolic sand dunes (parabolic, in this sense, simply meaning U-shaped). Years of erosion of the nearby scarps (steep slopes), the consistent presence of wind, and steady accumulations of sand, have all led to the growth and stability of these dramatic dunes (Guide’s Guide).

In 1961, John F. Kennedy established the Cape Cod National Seashore, which includes over 40,000 acres of land, as a United States National Park (Nature). Since then, the National Park Service has worked diligently to maintain the sand dunes through beach-grass planting efforts (Guide’s Guide) and regular monitoring. Westerly winds have hits the dunes consistently for decades, opening their centers so that they now all face west.

According to statistics published in 2008, nearly six million people visit Cape Cod each year, with over 60% of them visiting in the summer months (Cape Links). Despite this dramatic influx of tourists, however, Cape Cod remains in many ways a natural wonder. At the same time, Cape Cod has recently faced significant pollution problems, with the issue becoming increasingly worrisome with each passing year. In a mere forty years, between 1950 and 1990, the population of Cape Cod grew by 400  percent, with septic systems making up 97 percent of the total waste removal on the peninsula (wicked local). This increase has caused rising nitrogen to end up in the groundwater and bodies of freshwater throughout the area. In addition, climate change and elevated water levels are affecting underground water tables, threatening the coastline, increasing the severity of storms, and influencing all of Cape Cod’s fresh water. As water tables rise, they cause fresh groundwater to float atop the denser saltwater (image at right), forming freshwater bubbles beneath the land’s surface. In addition, as sea levels rise, higher tides will jeopardize static shorelines and shallow septic systems (eco-RI). When the water comes into contact with septic systems, it contributes to the already contaminated water source. Although many efforts have been made, and continue to be made, to maintain the natural beauties of Cape Cod, there is still great potential for the historic seaside towns to be overtaken by pollution, overpopulation, and other hazards. Thus, it is vital that society continues to work towards an overall urbanatural balance, seeking ways for the ever-increasing human populations to live in accord with their environment. –Kerin Maguire

percent, with septic systems making up 97 percent of the total waste removal on the peninsula (wicked local). This increase has caused rising nitrogen to end up in the groundwater and bodies of freshwater throughout the area. In addition, climate change and elevated water levels are affecting underground water tables, threatening the coastline, increasing the severity of storms, and influencing all of Cape Cod’s fresh water. As water tables rise, they cause fresh groundwater to float atop the denser saltwater (image at right), forming freshwater bubbles beneath the land’s surface. In addition, as sea levels rise, higher tides will jeopardize static shorelines and shallow septic systems (eco-RI). When the water comes into contact with septic systems, it contributes to the already contaminated water source. Although many efforts have been made, and continue to be made, to maintain the natural beauties of Cape Cod, there is still great potential for the historic seaside towns to be overtaken by pollution, overpopulation, and other hazards. Thus, it is vital that society continues to work towards an overall urbanatural balance, seeking ways for the ever-increasing human populations to live in accord with their environment. –Kerin Maguire

The Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is an extraordinarily complex ecosystem and the largest estuary in the United States. Numerous rivers, streams, plants, and wildlife–along with human encroachments–encompass the rich ecosystem of the Chesapeake. Within any ecosystem, there are divisions and distinctions between varying levels of living things. For example, the base of the Chesapeake’s ecosystem consists of organisms called benthos, which is a word of Greek origin meaning, “depths of the sea” (The Bay Ecosystem). These organisms include clams, oysters, sponges, and barnacles, among many others. Larger organisms such as blue crabs and striped bass then consume these organisms and contribute to the overall health of the Bay.

The Chesapeake has become widely associated with the Blue Crab. Not only are these crustaceans crucial to the ecosystem, serving as both consumer and consumed, they also play a large role in the economic wellbeing of many local fisheries (Blue Crabs). The results of a survey taken in 2015 estimate that over 400 million Blue Crabs live in the Chesapeake Bay; of them, about 100 million are adult females (Blue Crabs). The number of adult female crabs has increased by over 30 million since 2013. Several factors including limited bay grass to feed on and increased pollution have proven very detrimental to the Blue Crab population. Like Blue Crabs, Chesapeake Bay oysters are crucial to the Bay’s ecosystem and have supported local businesses for centuries. Oysters are filter feeders by nature: they take in water, trap particles such as chemicals and their own food, and then release the cleaner water back into the Bay. By doing this, oysters keep the water around them much cleaner–and clearer–than it would otherwise be. In fact, one oyster can filter over 40 gallons of water in a single day (Oysters). Oysters, however, have been historically over-harvested. In addition, the deterioration of their environment and parasitic diseases have both led to a dramatic decline in the oyster population (Oysters). Today, commercial oyster fishing has declined so far as to be almost negligible.

Likewise, maintaining a stable number of Striped Bass is essential to preserving a balanced ecosystem in this massive estuary. As one of the top predators in the Bay, there must be a sufficient number of organisms for these bass, and other fish species, to consume. In addition, they produce a commercial fishery that has supported–no to mention fed–virtually millions of human beings in Maryland, Virginia, and elsewhere. Around the 1970s and 1980s, however, the number of Striped Bass experienced a sharp decline. In 1973, the commercial fishery produced over 14 million pounds of of this flavorful fish; however, just ten years later fisheries failed to catch even two million pounds worth (Striped Bass). To fight this problem, the Atlantic Striped Bass Conservation Act was passed in 1984 (Striped Bass). By 1995, thanks to consistent efforts at conservation–and successful breeding programs–levels of Striped Bass were back to their earlier highs. –K.M.

The Pine Barrens

The Pinelands of New Jersey and the Pinelands National Reserve include over one million acres of land in Southern New Jersey. The area covers parts of seven counties including Ocean, Camden, and Atlantic (Frequently Asked Questions). The soil found in the Pine Barrens is not effective for extensive farming and agricultural growth and is described as “sandy, sometimes gravelly, porous, acidic and does not retain enough moisture” (Pinelands Alliance). However, both blueberries and cranberries thrive in such otherwise barren growing environments. In fact, New Jersey ranks fifth in blueberry production and third in cranberry production nationwide (The Garden State). The wet-harvesting method commonly used to pick cranberries was established in New Jersey around 1960 (Pineland Alliance). Wet harvesting fills each bog with water, allows the cranberries to float to the top of the bog, and then separates all the cranberries from their vines.

Aside from the folklore surrounding the notorious Jersey Devil (an 18th-century legend about a creature with bat-wings, a goat or horse head, razor-sharp claws, and the overall appearance of a devil), deep within the heart of the Pinelands lies another true mystery. The Pygmy Pine Plains, or Dwarf Plains, have long been enigmatic. Like the Pine Barrens themselves, the Pygmy Pine Plains are composed of several varieties of trees, including Pitch Pines and Blackjack Oaks (Pineland Alliance). However, all of the the trees that make up this area typically grow no “higher than one’s knee” (Pinelands Alliance). Many have suggested that this impediment to growth is the result of numerous factors: forest fires, nutrient-poor soils, and regularly high winds (Pinelands Alliance).

The Pine Barrens house a vast number of plants and wildlife. Hundreds of species of plants, including endangered and carnivorous pitcher plants and sundews, are plentiful in this area of New Jersey. In addition, the Pine Barrens Gentian is an endangered species of flower found in the Pineland area. Several factors, including commercial development and alteration of water sources, have proven detrimental to these plants (USBG). In addition, the Pine Barrens houses a wide variety of wildlife throughout the year, including 35 mammals, over 100 migrating birds, and several different reptiles, amphibians, and fish (Pinelands Wildlife). Stockton University, in close proximity to the Pine Barrens, has been thinning the woods surrounding its campus for research. Thinning the trees enhances the forest by preventing hazards such as fires and insect infestation (Hetrick).

Credit: U.S. Botanic Garden

How do the Pine Barrens relate to urbanature? Quite simply. Like other nature preserves, the Pine Barrens are located in the center of a busy, populated urban region, between Philadelphia and New York City. In addition, The Garden State Parkway and the Atlantic City Expressway serve as commuter paths for an endless number of year-round New Jersey travelers, both highways running directly through the Barrens. Despite these urbanizing factors, many areas of the Pine Barrens remain undisturbed. In the 1960’s, John McPhee, author of The Pine Barrens, spent several months exploring and mapping the area. His awestruck reaction was quickly overcome by angst as he pictured the potential future of the area. Luckily, the book caught the attention of many readers, including James Florio, former Governor of New Jersey, who began working hard to preserve much of the land that still covers over one-million acres (News Transcript). Today, the Pine Barrens and its natural inhabitants live more-or-less harmoniously with the countless commuters who drive through its prodigious, horizon stretching, trees each day. –Kerin Maguire

Green Mountains

As with many other states,the 1900’s saw significant damage to the forests of Vermont, due primarily to uncontrolled logging. To fight the destruction of such a natural area, Vermont’s National Forest was established in 1932 (History and Culture). Since this initiative, much of the foliage of this region has been restored, and continues to heal. The Green Mountain National Forest spans approximately 400,000 square miles (fs.usda.gov history) and encompasses several historic and recreational sites. Among the attractions of the Park are The Appalachian National Scenic Trail (which originates in nearby Maine), ski areas, and hiking, walking, and cycling paths (About the Forest). In addition, the forest is home to several important species of tree, including both Northern hardwoods and softwoods (About the Forest). In 2006, the Green Mountain National Forest proposed a final Land and Resource Management Plan to extend the protection of the park into the future (Executive Summary). Edward P. Cliff, the Ninth Chief of the USDA Forest Service notes: “As the population of the country rises and demands on the timber, forage, water, wildlife, and recreation resources increase, the national forests more and more provide for the material needs of the individual, the economies of the towns and States, and contribute to the Nation’s strength well-being. Thus the national forests serve the people” (Executive Summary).

As with many other states,the 1900’s saw significant damage to the forests of Vermont, due primarily to uncontrolled logging. To fight the destruction of such a natural area, Vermont’s National Forest was established in 1932 (History and Culture). Since this initiative, much of the foliage of this region has been restored, and continues to heal. The Green Mountain National Forest spans approximately 400,000 square miles (fs.usda.gov history) and encompasses several historic and recreational sites. Among the attractions of the Park are The Appalachian National Scenic Trail (which originates in nearby Maine), ski areas, and hiking, walking, and cycling paths (About the Forest). In addition, the forest is home to several important species of tree, including both Northern hardwoods and softwoods (About the Forest). In 2006, the Green Mountain National Forest proposed a final Land and Resource Management Plan to extend the protection of the park into the future (Executive Summary). Edward P. Cliff, the Ninth Chief of the USDA Forest Service notes: “As the population of the country rises and demands on the timber, forage, water, wildlife, and recreation resources increase, the national forests more and more provide for the material needs of the individual, the economies of the towns and States, and contribute to the Nation’s strength well-being. Thus the national forests serve the people” (Executive Summary).

National forests exist for their own sake, but also for the good of society; thus, their preservation is essential. One of the sections of the proposed plan to do so in the Green Mountains includes forest health in general, noting increasing global disease and insect threats. In addition, management tactics such as pesticides, are potentially detrimental to ecosystems within these forests and elsewhere (Executive Summary). The Green Mountains serve as the home to a variety of wildlife species: over 15 different kinds of fish, and around 400 types of vascular plants (Executive Summary).

National forests exist for their own sake, but also for the good of society; thus, their preservation is essential. One of the sections of the proposed plan to do so in the Green Mountains includes forest health in general, noting increasing global disease and insect threats. In addition, management tactics such as pesticides, are potentially detrimental to ecosystems within these forests and elsewhere (Executive Summary). The Green Mountains serve as the home to a variety of wildlife species: over 15 different kinds of fish, and around 400 types of vascular plants (Executive Summary).