Cervical cancer is a leading cause of cancer and cancer death across the globe, particularly in countries with low human-development index. There were over 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer, and 311,000 deaths in 2018 alone. And this illness is one of the many that shows the devastating healthcare disparities across the globe with almost 9 in 10 deaths from cervical cancer occurring in less developed regions.

But why are we seeing such high death rates from cervical cancer if we know the leading cause?

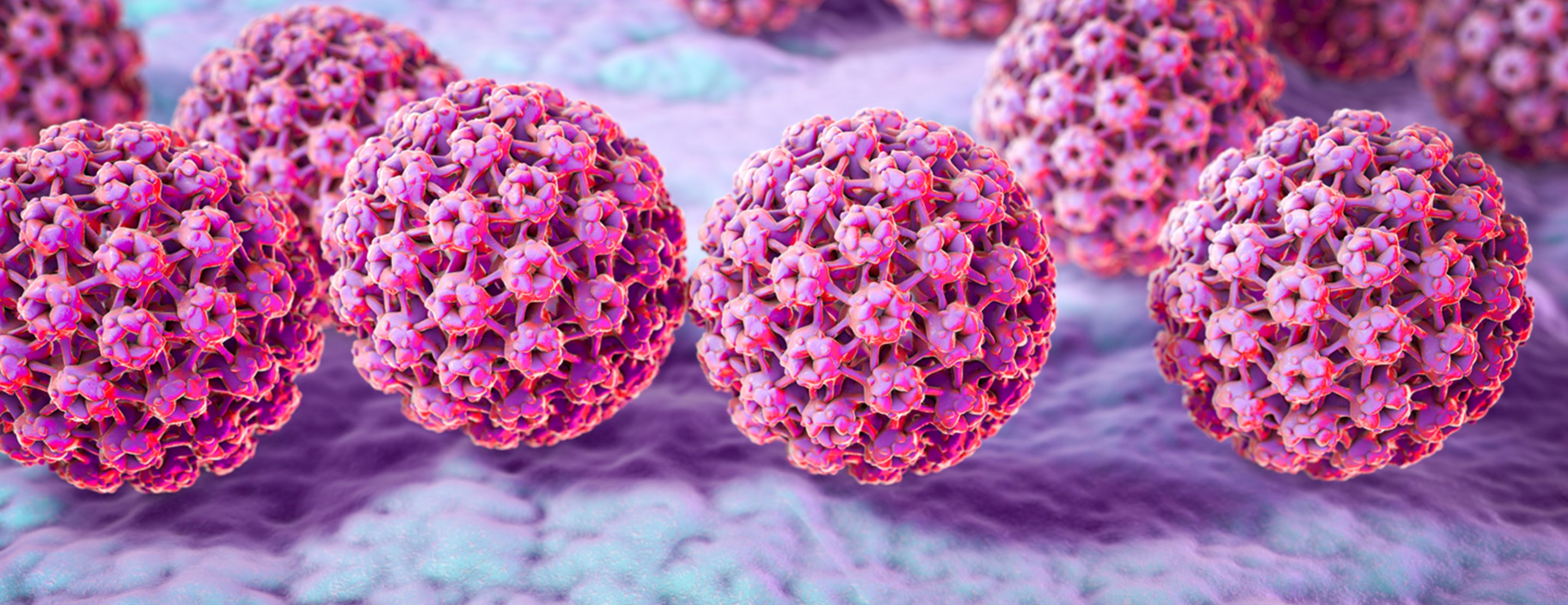

You may be aware that human papillomavirus (HPV) is strongly linked to incidence of cervical cancer. But in fact, almost all cervical cancer cases are caused by HPV, as well as some other cancers. HPV is thought to be responsible for more than 90% of anal and cervical cancers, about 70% of vaginal and vulvar cancers, and 60% of penile cancers. That’s a lot of cancers caused by one virus!

Human papillomavirus infection (https://www.ucsfhealth.org/en/medical-tests/007762)

HPV is thought to be responsible for more than 90% of anal and cervical cancers, about 70% of vaginal and vulvar cancers, and 60% of penile cancers.

It is important to note though that there are many types of HPV, which are often divided into ‘low-risk’ (wart-causing) or ‘high-risk’ (cancer-causing), based on whether they put a person at risk for cancer. Normally, our body’s immune system is able to fight the HPV infection and get rid of it naturally within two years. However, when the body’s immune system cannot get rid of a high-risk HPV infection, it can linger in the body and transform normal cells to abnormal cells which become cancerous.

Since evidence shows that HPV can cause many cancers and it has a high prevalence, i.e. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States with nearly 80 million people currently infected, researchers have developed vaccines against HPV. Vaccines are available that protect individuals against the cancer-causing HPV types, and these have the possibility to prevent most cases of cervical cancer. However, to date, the administration and uptake of HPV vaccines is insufficient to have a profound impact on global cancer rates. Over the next 65 years, current vaccination strategies are projected to avert only 3% of the nearly 20 million new cases and 10 million deaths from cervical cancer globally. However, if vaccination was more widespread the reduction would be significantly higher. This is a very frustrating circumstance we find ourselves in! HPV causes most cervical cancers; we have an HPV vaccine that can prevent infection; yet it is not being administered at high enough levels to have a significant impact on reducing cervical cancer deaths. Unfortunately, there are many factors that limit widespread vaccination.

Retrieved from Flickr

Mainly skepticism and the spread of misinformation about vaccines in developed countries; as well as cost, lack of access and limited availability in low-income countries. Currently, the recommended HPV vaccine dosage includes two to three regimens, which understandably can be difficult because patients need to follow-up months later and adhere to their schedule.

However, there may be hope for more widespread vaccination.

An article published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute on February 24th, 2020 reported that a single dose of an HPV vaccine may be just as efficacious as the recommended dosage of three regimens. If individuals only needed to receive one dose, this could increase vaccine implementation and uptake, especially in less developed regions, because it is logistically easier and cheaper.

The data reported in this article comes from a Costa Rica HPV vaccine trial, sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. The Costa Rica trial was originally designed as a 4-year randomized trial where women received 3 doses of the HPV vaccine and were compared to unvaccinated individuals. Dr. Kreimer, the lead researcher, and colleagues followed up with most HPV-vaccinated women beyond the 4 years of the original trial. About 20% of the women received fewer than the recommended doses due to reasons such as pregnancy or abnormal cervical findings from routine cervical cancer screening. This unplanned difference allowed researchers to compare outcomes between single dose and multiple dose individuals.

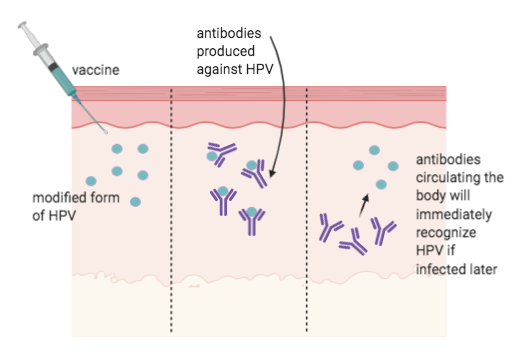

During vaccination, a vaccine with modified forms of the virus is injected into the body (left). The vaccine stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies against HPV. The immune system learns to recognise the virus, so that if the body is later infected with the live disease it will produce antibodies to attach to the virus and stop the infection. (Created in Biorender).

Analysis of the data showed that women who received a single dose of HPV vaccine continued to be protected against cervical infection by the two main cancer-causing HPV types targeted by the vaccine. How can we tell they are protected?

100% of the HPV-vaccinated women (single and multiple dose) remained seropositive at 9 and 11 years post administration, meaning that antibodies to the main cancer-causing HPV types remained in their blood.

Antibodies are chemicals created by the body when they identify a foreign invader (i.e. HPV vaccination) that are able to fight specifically against that foreign invader. Hence, 11 years later all women who were vaccinated still had the ‘tools’ needed to fight an HPV infection. Antibody levels were comparable to those seen in the early years following vaccination, regardless of the number of doses received, an indication of long-lasting immune response to the vaccine. Additionally, the reduction in HPV infections was similar no matter how many vaccine doses were received, with an estimated vaccine efficacy of 82%, 84 %, and 80%, respectively, for one, two, and three doses. (Vaccine efficacy is the reduction in infections in vaccinated versus unvaccinated women.)

In a second, related analysis, the trial’s researchers found that a single vaccine dose also provided long-lasting protection against three other cancer-causing HPV types not targeted by the vaccine—a phenomenon known as cross-protection. The ability to protect against many cancer-causing HPV infections with just one vaccine dose—rather than the two or three doses currently recommended—”would make a very big difference” in preventing the more than half a million new cervical cancer cases and more than 300,000 deaths from the disease worldwide each year, said Costa Rica Trial investigator Aimée Kreimer, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG).

Although the results of the two new studies are very encouraging, there are some limitations: relatively few women in the Costa Rica Trial received one or two vaccine doses, and they were not randomly assigned to the specific dosing schedule. Therefore, other trials, including a randomized NCI-led ESCUDDO study in Costa Rica are needed to confirm that a single dose of HPV vaccine is sufficiently protective and if it is as effective as multiple doses. Such findings could support worldwide changes in vaccination guidelines, leading to an increased impact on cervical cancer rates.

Aimée R Kreimer, PhD, Joshua N Sampson, PhD, Carolina Porras, MSc, John T Schiller, PhD, Troy Kemp, PhD, Rolando Herrero, MD, Sarah Wagner, BSc, Joseph Boland, PhD, John Schussler, BS, Douglas R Lowy, MD, Stephen Chanock, MD, David Roberson, BS, Mónica S Sierra, PhD, Sabrina H Tsang, PhD, Mark Schiffman, PhD, Ana Cecilia Rodriguez, MD, Bernal Cortes, PharmD, Mitchell H Gail, MD, PhD, Allan Hildesheim, PhD, Paula Gonzalez, MD, Ligia A Pinto, PhD, the Costa Rica HPV Vaccine Trial (CVT) Group, Evaluation of durability of a single-dose of the bivalent HPV vaccine: the CVT Trial, JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, , djaa011, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa011

Alex

I was intrigued throughout the whole article! This is such an interesting topic, and important to know more about. I really liked the incorporation of a couple studies, but mostly that you mentioned flaws or limitations that are still present even after the completion of the studies. That’s very important information to ensure the proper understanding of the use of HPV treatments.