From delicious Abalone, to swarms of bright red krill and plankton too small to see with the naked eye, coastal invertebrates make up the basis of the oceanic food chain. A recent study however, suggests climate change is putting these vital organisms at risk.

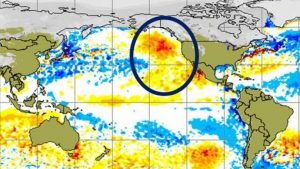

Above is a thermal heat map of the Pacific Ocean in 2015. The notorious 2015 warm blob is highlighted by the circle. Cooler water is depicted by different shades of blue while warmer water is depicted by yellow and reds. (Image courtesy of NOAA National Climate Data Center)

According to researchers at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology, coastal invertebrates are declining and warming ocean temperatures are to blame. The study which took place over the course of three years near the mouth of Coos Bay estuary in Oregon, concluded populations of coastal invertebrates failed to spawn between the years of 2015 and 2016. The researchers also concluded that marine heat waves (MHWs) or abnormally high ocean temperatures were to blame.

Starting in 2015, a body of abnormally warm water parked itself in the Northeastern Pacific. The phenomena are referred to as “warm blobs”, and climatologists say the 2015 blob is a direct result of human induced climate change. Unfortunately, the following year was characterized by an uncharacteristically warm El Nino event. These events occur naturally and result in warmer Pacific Ocean temperatures.

Normally, trade winds blow across the Pacific from east to west. As these winds move westwards, warm water is pushed away from Central and South America and towards Southeast Asia and Australasia. As a result of this displacement of water, cooler water from deep within the Pacific is forced upward in a process called upwelling.

Upwelling allows for nutrients deep within the Pacific to be cycled to the surface. These nutrients fuel the great diversity of life that can be found across the Eastern Pacific, from large schools of sardines to Humpback Whales, and Californian Sea Lions. Coastal Invertebrates are among these vital nutrients.

The temperature difference caused as a result of these trade winds and by upwelling, are also believed to play a big role in the reproductive cycles of coastal invertebrates. According to the study, cooling water triggers a process known as gametogenesis, which results in gamete or sperm and egg formation.

The production of gametes is a necessary step in the reproductive cycles of most invertebrates. If this process goes un-triggered as a result of stagnant ocean temperatures, researchers fear that spawning events will become less frequent. Such scenarios not only could lead to declines in the populations of costal invertebrates but could also set off a trophic cascade, in which organisms further up the food chain such as the Sardines, Humpback Whales, and Sea Lions, also decline.

According to marine ecologist Dr. Vonda Cummings, as a result of global climate change, “the oceans are changing faster than many organisms can adapt”. This is because, as Dr. Cummings puts it, “Many marine organisms have evolved to live in a very narrow band of temperature”.

In other words, if ocean temperatures rise above the preferred temperature at which an organism has evolved to live, then marine ecosystems around the globe could suffer. According to the study, signs of this catastrophe are already visible. 2018 and 2019 saw two additional “warm blob” events form off the west coast of the United States.

The researchers warn, that fisheries will be drastically impacted and will be forced to change fishing tactics and practices in order to cope with changes in ocean chemistry. Unfortunately, many fisheries have already failed as a result of poor harvests and a collapse in fish prices.

While some impacts of global climate change will be inevitable, hopefully going forward we can adapt to our rapidly changing planet, and act to counteract this change, and restore our oceans.

References:

Shanks, L. A., Rasmuson, K. L., Valley, R. J., Jarvis, A. M., Salant, C., Sutherland, A. D., Lamont, I. E., Hainey, A. H. M., and Emlet, B. R. 2020. Marine heat waves, climate change, and failed spawning by coastal invertebrates. Limnology and Oceanography:65, pp 627-636.

Alex

"This title was very eye catching! That is so interesting that such a ..."

Alex

"This is really interesting! The fact that crops and plants are damaged is ..."

Alex

"Well done, this article is great and the information is very captivating! Ethics ..."

Alex

"I was intrigued throughout the whole article! This is such an interesting topic, ..."

Alex

"This is such an interesting article, and very relevant!! Great job at explaining ..."

Grandpa

"Honey You Did a good job I will forward to my eye doctor "

murphymv

"This article is fascinating because it delves into the details of the research ..."

murphymv

"I agree, adding the photo helped solidify the main finding. "

murphymv

"This is a fascinating finding. I hope this innovative approach to improving transplants ..."

Sherzilla

"This is a great article! I would really love to hear how exactly ..."

Sherzilla

"It's disappointment that these treatments were not very effective but hopefully other researchers ..."

Sherzilla

"I agree with your idea that we need to shift our focus to ..."

Sherzilla

"It's amazing to see how such an everyday household product such as ..."

Lauren Kageler

"I will be interested to see what the data looks like from the ..."

Lauren Kageler

"A very interesting article that emphasizes one of the many benefits that the ..."

maricha

"Great post! I had known about the plight of Little Browns, but I ..."

Sherzilla

"I assumed cancer patients were more at risk to the virus but I ..."

Sherzilla

"Great article! It sheds light on a topic that everyone is curious about. ..."

maricha

"This article is full of really important and relevant information! I really liked ..."

maricha

"Definitely a very newsworthy article! Nice job explaining the structure of the virus ..."

maricha

"It's interesting to think that humans aren't only species dealing with the global ..."

murphymv

"This is very interesting and well explained. I am not too familiar with ..."

Lauren Kageler

"Great article! This post is sure to be a useful resource for any ..."

Lauren Kageler

"Definitely seems like an odd pairing at first, but any step forward in ..."

murphymv

"What an interesting article! As you say, height and dementia seem unrelated at ..."

murphymv

"Great article! I learned several new methods of wildlife tracking. This seems like ..."

murphymv

"Very interesting topic! You explained cascade testing and its importance very well. I ..."

Alex

"This article is really interesting! What got me hooked right away was the ..."

Sabrina

"I found this article super interesting! It’s crazy how everyday products can cause ..."

Erin Heeschen

"I love the layout of this article; it's very eyecatching! The advancements of prosthetics ..."

murphymv

"Awesome article! I like the personality in the writing. Flash Graphene not only ..."

murphymv

"Very interesting work! I don't know a whole lot about genetics, but this ..."

Cami Meckley

"I think the idea of using virtual reality technology to better help prepare ..."

Erin Heeschen

"I wonder if there's a connection between tourist season and wildfires in the ..."

Ralph berezan

"Not bad Good work "

Michelle

"This sounds like it would be a great tool for medical students! ..."