While visiting the Museum of the Salvadoran Revolution in Perquín, Morazan, what struck me most was the museum’s vast dedication to displaying various international posters that specifically address and resist U.S. imperialism in El Salvador/Central America. The posters at the museum ranged in origin from neighboring Latin American countries (Honduras, Nicaragua, Brazil, Guatemala, etc.) to (unspecified) Francophone nations and even the U.S. itself. This demonstrated a global awareness of many of the injustices being perpetuated by the U.S. against El Salvador in the events leading up to and during the civil war. Many of these posters displayed phrases like “Stop bombing El Salvador” and “U.S. out of El Salvador!” in order to address the U.S. government’s instrumental role in supporting the Salvadoran right-wing military through funding, trainings, and other direct involvement.

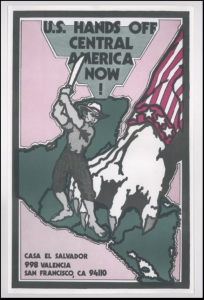

Upon searching for more information on the Salvadoran Civil War in the Latin American Digital Initiatives through the University of Texas Libraries, I came across the Colección Conflicto Armado, from el Museo de la Palabra y el Imagen (Armed Conflict Collection from the Museum of the Word and Image) in San Salvador, El Salvador. One of the posters I was most interested in is pictured here:

The poster depicts a man dressed in attire typical to campesinos (peasant farmers) holding a corvo (or machete) over his head, in preparation to attack the large and imposing clawed hand that digs into the map of Central American land. The clawed hand is representative of the United States, indicated by the sleeve that bears stars and red and white stripes. Further, the specificity in relevance to the Central American region is made clear by the way the poster isolates the region from its neighboring Latin American countries, and thus centers Central America and the U.S.’s particular role in Central American countries. Through its imagery, the poster characterizes the campesino, in an empowered way, as the central force to resisting the U.S. imperial hand.

The use of the corvo as the campesino’s method of resistance is significant in its indication of class—especially in focusing on a war with origins in the exploitation of the poor and widespread socioeconomic inequalities. As Manlio Argueta remarks throughout his novel Un dia en la vida (1980), the first sign of a Salvadoran campesino man is that he treats his corvo like an extension of his own hand—it is a tool essential to his everyday work but it is also a tool necessary to the campesino man’s defense and protection of his family. In the poster, the corvo is presented as the campesino’s means of resisting U.S. imperial power. While the corvo is positioned so as to attack the clawed hand, it is, interestingly, literally attacking the very word “America” at the top of the poster. The poster therefore highlights the campesino’s corvo as a critical to subverting U.S. power.

Ultimately, the poster’s purpose is made clear in its headline: “U.S. Hands Off Central America Now!” Written in English and produced in the United States at Casa El Salvador in San Francisco, CA, the poster targets English-speaking audiences and is especially relevant to American citizens. It is an important record of how American communities and organizations were responding to the Reagan administration’s continued support of the Salvadoran government during the civil war. This is helpful to my research because it enables a continued broadening of my understanding of the Salvadoran Civil War in both ‘homeland’ and ‘diaspora.’

Although my initial research scan to find the exact purpose or role of Casa El Salvador has not been conclusive, its very name leads me to assume that it was possibly a community organization dedicated to issues in El Salvador but likely also one that was invested in Salvadoran communities living in the United States. Especially given its location in California, such an organization would have likely been accessible to many Salvadoran refugees who fled El Salvador in the events leading up to the war or once it had begun. Continuing to research primary documents will be essential to deepening my understanding of the historical contexts and sociopolitical implications of Salvadoran resistance. These sources will further inform my work, as I begin to analyze the role of resistance in Salvadoran writing.

The concept of your blog post is very interesting, and I really appreciated your thorough analysis of Posters of Resistance, particularly the “U.S. Hands Off Central America Poster.” Your discussion of the concept of audience was really enlightening to me because at first glance, I would have assumed that these types of rebellion posters would have been largely circulated among people within El Salvador and Central America in order to further inspire resistance. The fact that the language of the poster being English signifies that the poster’s intended audience was most likely people in the United States was an apt conclusion, and this insight really enabled me to reflect on how components of the works that I am reading for my own thesis, such as their original language, suggests that they were read by (and intended to be read by) people of a particular region.

Your comprehensive understanding and research into the history of El Salvador and the war is impressive, and I think that this information will serve you well when you beginning to write you thesis in the future. I understand the concern that you expressed in class about not being sure about when to stop engaging in historical analysis and when to begin engaging in literary analysis, but it seems as though the two are working simultaneously in this blog post, so I think that you are definitely on the right track.

Moving forward, it might be interesting for you to look into how these posters were actually circulated throughout the United States. I imagine that the U.S. government and Regan administration would have wanted to prevent such posters from being viewed by the general public, so this might be a worthwhile investigation. Amazing post Janel!