(i) Secondary & Theoretical Texts

- Poets and Prophets of the Resistance: Intellectuals and the Origins of El Salvador’s Civil War (2017) Joaquín M. Chávez.

Aldo A. Lauria-Santiago and Jeffrey L. Gould. “Memories of La Matanza: The Political and Cultural Consequences of 1932.” To Rise in Darkness: Revolution, Repression, and Memory in El Salvador, 1920-1932. (2008) - U.S. Central Americans: Reconstructing Memories, Struggles, and Communities of Resistance (2017) ed. Karina O Alvarado; Alicia Ivonne Estrada; Ester E. Hernández.

- Arias, Arturo. “Central American-Americans: Invisibility, Power and Representation in the US Latino World.” Latino Studies (2003): 1.1.

- Rodriguez, Ana Patricia “Diasporic Reparations: Repairing the Social Imaginaries of Central America in the Twenty-First Century” Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature (2013):. 37: 2.3

Rodriguez, Ana Patricia. “’Departamento 15′: Salvadoran Transnational Migration and Narration.” Dividing the Isthmus: Central American Transnational Histories, Literatures and Cultures. University of Texas Press, 2009 - Mignolo, Walter D. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options.

Cárdenas, Maritza/ “From Epicentros to Fault Lines: Rewriting Central America from the Diaspora,” Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 37: Iss. 2, Article 8. 2013.

(ii) Academic Journal

Latino Studies. ed. Lourdes Torres. Palgrave Macmillan UK, ISSN: 1476-3435 (Print) 1476-3443 (Online)

(iii) Key terms

Central American Civil Wars, Salvadoran Diaspora, Transnational Migration

(iv) Primary Texts

Primary texts:

- Javier Zamora, Unaccompanied. Copper Canyon Press, 2017.

- Alexandra Lytton Regalado, Matria, Black Lawrence Press, 2017.

- William Archila, The Art of Exile. Bilingual Review Press, 2007.

- Yesika Salgado, Corazon. Not a Cult Press, 2017.

- Javier Zamora, Selected Poems: “El Salvador,” “Saguaros,” Poetry Foundation.

- Yesika Salgado, Selected Poems: “Translation,” “Brown Girl,” “On The Good Days,” YouTube.

- The Wandering Song: Central American Writing in the U.S. ed. Leticia Hernández-Linares, Rubén Martínez, and Héctor Tobar. Tia Chucha Press/Northwestern University Press, 2017.

- Kalina: Theatre Under My Skin, Contemporary Salvadoran Poetry / Teatro bajo mi piel, poesía salvadoreña contemporanea. ed. Alexandra Lytton Regalado. Editorial Kalina, 2014.

- Manlio Argueta, Un Dia en La Vida. (1980) UCA Editores.

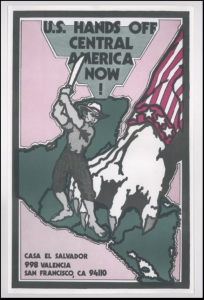

My research process thus far in compiling this list has built upon the following logic: If I am setting out to write a thesis focusing on literature of Salvadoran diaspora, then I cannot do so without also thinking critically about immigration. And if I am to discuss Salvadoran immigration in my thesis, then I cannot do so without centering the 1980’s Civil War as a main cause of influxes of Salvadoran refugees fleeing El Salvador to immigrate to the U.S. Joaquín M. Chavez’s book will provide a more contextual background of both general and specifically literary resistance relating to the events leading up the Salvadoran civil war. Otherwise, the next three sources on my list are texts that provide contextual understandings and summaries of how the twentieth century civil wars in Central America have shaped the Central American diaspora in the United States. I spoke with Professor Vazquez about these sources, with the goal of narrowing down to select texts that will enable me to understand the current critical/scholarly conversation on “Central American-Americans.” I have also specifically selected scholars whose work engages directly with literature or who have otherwise done research or written about Central American literature, both in homeland and diaspora. As I browse through journal issues of Latino Studies I also aim to maintain my focus on what critics are saying about Latino literature as a whole, or aspects/regions that I could study in comparison to Central American/Salvadoran literature.

Ultimately, I want to study the ways in which Salvadoran literature is informed by historical contexts including legacies of colonization and U.S. neoliberal intervention, which is precisely where Mignolo’s writings on decoloniality in Latin America will help provide a more theoretical backing to my work. Further, I want to specifically examine how Salvadoran writers use story as a means of resistance in opposition to wider systemic oppressive frameworks. Some of the questions I am beginning to raise are: How do writers of Salvadoran origin use their literary work to engage with and comment politically on key political events in the twentieth century (specifically, the 1932 uprising and the 1980’s civil war) and their aftermath? How do Salvadoran writers use story as a means of resistance, and what, specifically, do their stories resist? What happens to Salvadoran writing when it moves beyond Salvadoran borders, and what does this writing reveal?

Research update 10/23/17:

The updated changes and additions to my reading list are motivated primarily by my efforts to continuously refine my research topic. As I expand my knowledge on Salvadoran literature, I have been conscious of selecting sources that are as close and specific to the questions I seek to address. I aim to focus on Salvadoran poets writing in the United States and examine the ways in which their writing reflects resistance and/or resilience. As previously mentioned in my original post, in order to do this, I know that my research and analysis needs to maintain a consciousness for the conditions of migration and the related historical contexts. For this reason, I have sought out sources that directly discuss Salvadoran migration and Salvadoran literature in diaspora.

While Joaquín M. Chavez’s book provides a comprehensive analysis of the events and movements that led up to the Salvadoran Civil War, I realized that what I was most interested in was studying the catalyzing event: the 1932 indigenous uprising; so, instead of reading Chavez’s work, I selected a critical article that specifically analyzes the effects of that revolution in regard to the way it is remembered in Salvadoran communities. Rather than trying to understand all the complexities of the twentieth century historical contexts (an impossible task, given my research time frame), I am making efforts to select specific significant events, so as to use my understanding of those events to shape my analysis of their lasting impact. I swapped out one of Ana Patricia Rodriguez’s articles on Central American migration for one that focuses more specifically on Salvadoran migration to the United States. Finally, when I began to read through Walter Mignolo’s book, I realized that although his theoretical framework on decoloniality will be useful, it is not as relevant to the specific questions I am raising regarding diaspora. I intend to keep his work in mind and refer to it if and when applicable, but I opted to swap this source out in order to focus on one that deals more critically with what it means to write from Central American diaspora.

My primary texts feature the poetry collections of four key Salvadoran poets writing in the United States (Zamora, Regalado, Archila and Salgado), as well as a few additional poems from two of them(Zamora and Salgado). I have included two videos of Salgado’s work as a poet and performer in U.S. poetry slam communities. Her performances of her poems add a new layer of analysis, particularly in considering her impact in popularizing Salvadoran narratives via her powerful social media presence. In addition to these works, two other primary texts are anthologies of Central American writing and Salvadoran writing respectively. The only work on my list written by a “homeland” Salvadoran writer is Manlio Argueta’s Un Dia en La Vida and I am most interested in its representation of U.S. intervention in the Salvadoran Civil War.