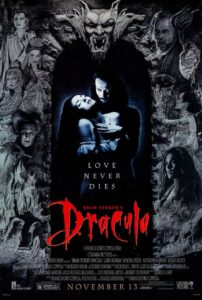

Since its original publication, Dracula has been changed and so have vampires in general. In class, we discussed a lot about sexual repression in the novel, particularly surrounding Lucy. In the 1992 adaptation of Dracula, “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” with Gary Oldman, there is light shed on the sexual repression. In this post I will be focusing on the movie poster (at the bottom of the post) as the setup of it is a lens itself. In the poster, the main spotlight is Dracula holding Mina with her head tilted back and eyes closed. On the poster she is seen in a dress that is very low on her shoulders and shows a lot of skin. This showing of skin shows her freedom from sexual repression as she is now open about her clothing and under her it says, “love never dies.” In this regard, the poster shows this idea that Dracula grants Mina sexual freedom. Viewing the novel from the lens of the movie poster, it can be interpreted that Dracula was in fact freeing the women and giving them their desires instead of holding them back or “killing” them. Using the catchphrase “love never dies,” vampires themselves (the undead) can be interpreted as love. In the novel, Lucy states “being proposed to is all very nice and all that sort of thing, but it isn’t at all a happy thing when you have to see a poor fellow, whom you know loves you honestly, going away and looking all broken hearted” (Stoker 65). In this scene, Lucy is writing to Mina about how she turned away from two of her suitors and had to reject them. However, when Dracula bites her, she fully gives in and tilts her head back for his bite. In this way, she desires Dracula and while the men may see this as a “magic power” he must seduce them, to Lucy she does not have to see a poor fellow go away sad because she wants this fellow. Also, her use of the word “nice” when talking about being proposed to is a very soft word, seeing Dracula as a lover instead of an evil monster, this word has a deeper meaning. While these human men are “nice” and “ok,” Dracula is passionate and especially according to this movie poster based on choice of actor, he is a “heartthrob.”

Another quote by Lucy furthers this idea that Dracula is a representation of love, especially one that grants sexual freedom. “I suppose that we women are such cowards that we think a man will save us from fears, and we marry him” (Stoker 66). This quote can be read as the fear of their own sexuality. In Victorian times, women were seen as pure and not sexual beings. Lucy, however, is very sexual as she says previously that if she could marry multiple men, she would do that. Even later in the novel, she has the blood of four men in her (which means she belongs to all of them). Instead of putting blood in her like the men do, Dracula takes it out of her, therefore claiming her and having her inside him. By being the one with her blood in him, he takes the role of the bride and grants Lucy her sexual freedom instead of her belonging to him. He also does the same to Mina and if we read Dracula through this lens of erotic and sexual freedom like the movie poster hints at, he is sort of a hero in our standards. Instead of taking away their freedom and trying to keep them pure, he lets them suck his blood and sucks theirs as well. Instead of forcing a blood transfusion on them, he gives them a choice and Mina and Lucy decide to love him and find their freedom in this way. Not only this, but he does not appear in mirrors, he does not have to face himself and have “morals,” instead he can choose to act and not necessarily have remorse. Dracula viewed through the lens of the 1992 poster is less scary and more so alluring and attractive unlike older depictions where he is hideous and purely evil. When looking at the poster, you feel drawn to Dracula and Mina’s life does not seem completely unpleasant.

If we apply the movie’s lens, that of “Lucy and Mina enjoy sex (did I say sex? I meant bloodsucking!) with Dracula and he liberates them from oppression,” it reframes their observed reactions to him. Mina yelling “unclean!” after she and Dracula do… stuff is less about her own feelings towards the act as it is about how this will change her relationship with Jonathan and the other men: she saw what happened to Lucy last time. The purpose of the women’s vilification of Dracula is now for the sake of their reputations.

I really like the idea of using the movie poster as a lens. This post makes a great point about Dracula representing love and freedom rather than destruction. I find it interesting that the humans still agree to destroy all vampires, including Lucy. Even though vampirism weaponized her sexuality as unholy and caused her to prey on innocent children, to some extent she was just the same Lucy but immortal. As soon as Lucy preys on children’s blood, potentially in order to repurify her own blood, the men decide she has to die. In the same way New Women were frowned upon, the men frown upon the new power and freedom Lucy has as a vampire. In this way, the men deeming Lucy’s death necessary supports this post’s argument that Dracula actually offered freedom.

The consensual recasting of Dracula and Mina’s relationship has definitely marked out a change in society’s views towards women’s sexuality. In the original Victorian novel, Dracula feeding on the women had to be an assault because nice women would never have a sexual appetite in the first place. So as time passes, it makes sense to rework the story to give Mina and Lucy that agency back. But I have to admit that when it comes to direct adaptations of Dracula, I find this kind of distasteful. I know that the novel’s own metaphors are fairly confused, given the language of Lucy’s staking, but Dracula feeding on both women is very clearly meant to be an assault, and it feels wrong to soften that. We understand now that women DO have sexual agency, but that doesn’t mean that all advances are desired, which is still an important message to convey in modern times! And while the treatment of Lucy’s advancing vampirism falls flat in a modern context, I actually thought the response to Mina’s attack was surprisingly supportive and nuanced, as the protagonists all accept Mina’s blamelessness and immediately try to protect her. I understand that in that cultural context, Mina being blameless and not wanting Dracula’s advances is the easiest thing for them to accept, but over a century later, Senf argued that Mina’s own account of not resisting made her complicit(??!), which is enough to convince me that the original version of the story is still important to tell.

I love your critical analysis of the movie poster and would push you further to think of this as a piece of media/advertisement. What does the poster say about society? I also would like to ask if you were to design a poster for the novel of what would it depict and what themes would it represent? On a different note, the phrase, “love never dies,” and the concept of blood transfusion can also be looked at through the lens of the disease of vampirism, and xenophobia as an extension, which we talked about in class and I investigated in my post. Further, Mina gives into the disease (Dracula/the Transylvanian/outsider), as you mentioned, and has to be rescued by white, British men. So much sexual tension there between Dracula and Mina, Mina and her husband and between the men especially! Last note, we should seriously have a class that compares the many variations of Dracula as a film!