Since the publication of Dracula, vampires have taken over a place in our cultural consciousness that no other phenomenon has come close to encompassing. Vampires smudge the line between terror and desire; in our modern conception of them, they are at once frightening, interesting, powerful, and eminently attractive. Anne Rice and Stephenie Meyer, plus countless other writers, have both taken advantage of and created the recent sensation and call for “supernatural” fiction: Twilight, Vampire Academy, Salem’s Lot, Interview with the Vampire. These have spawned their own offshoots involving witches, werewolves, ghosts, and a positive plethora of other beings.

These beings, like Dracula did in 1897, represent “the other” as intensely desirable, not only as physical representations of forbidden sexiness but as a potential lover or friend or spouse. Dracula’s physical appeal and mental power have been perpetuated and diluted by more recent characters in popular fiction – Edward Cullen, Adrian Ivashkov, Bunnicula – but the essence of Dracula as an idea is there in all of them. Searching the word “vampire” into Google Images brings up a few gory depictions of ghastly old men, but mostly the images are of young and beautiful people – who just happen to have fangs and/or blood dripping from their mouths. Because of Count Dracula, vampires are sexy.

To someone not steeped in our modern conceptions, vampires aren’t sexy at all; they have mutant teeth and they eat people. But in fantasy or “supernatural” novels (Dracula included, more notably books like Harry Potter, the Divergent series, the All Souls trilogy and a thousand more), it often turns out that the protagonist is the most “other” of all the others. Harry Potter is the wizard prophesied to defeat Voldemort; Tris is divergent; Diana Bishop is the witchiest witch of them all. We ourselves desire to be “the other” because we want to be different – the most special.

Or maybe this desire to be “the other,” the most powerful witch or the sexiest vampire or the bitiest werewolf, stems from a desire to be part of the community to which we’ve truly always belonged. (Harry leaves Privet Drive for the wizarding world.) This displacement into the place we were meant to be reflects fear that we’re not in the place that we actually belong, that we don’t fit in. And couldn’t the entire concept of a supernatural world conceal and reveal the fear that our own world is mundane, that our lives have too little meaning? A supernatural world right around the corner is so much better and more exciting – and in all the fantasy novels, the vampire novels, that world is the world where we truly belong.

What does this have to do with Dracula? Perhaps Count Dracula represents the ultimate other: foreign, sexy, powerful, and dead. Yet despite their revulsion, the characters in Dracula also feel a strange attraction to him – they describe him in uncomfortably physical language (“parted red lips,” etc), and Dracula’s enduring status as a figure not of violence and gore but of sex and even romance surely owes something to our own desire to see him that way. We want to be – not Dracula but something like him: our enchantment with Dracula stems from our attraction to the idea of the best, most special “other” – and finding out that the other is actually ourselves. Lucy’s transformation into something other than human and Mina’s close escape from the same fate mirror modern novels which involve the protagonist being the other all along and not knowing it. We all want to be that other – the most powerful, the most magical, the most special – despite the fear and discomfort that often come with it.

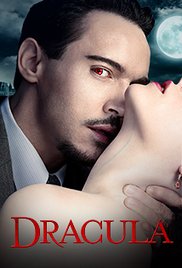

Dracula is a vampire; he is not Prince Charming. But the modern world – often including people who have actually read Dracula – see him as a blend of the two. The 2013 TV show Dracula shows him as a wounded hero seeking revenge and finding love; there he’s played not by a creepy old man but by Jonathan Rhys Meyers.

Dracula means sex and desire, often forbidden. He’s our fantasies. He’s the “other” we might want to be. He’s the desire for something different, something not like us – and the desire that the “us” we are be different. We love Dracula because we want what he represents – he is “the other” but, in his recent incarnations and in the novels Bram Stoker (directly or indirectly) inspired, he’s also ourselves.

I definitely agree that today there is the idea of the other as something we want to be, as something that defines someone as special – but that is not the only reaction. Today, there is still a feeling of the other as something terrifying – look at Trump’s ideas about immigration and “others” entering and being a part of our country. Othering is about fearing the unknown, or (even worse) thinking that you do know what these others will bring. There are plenty of close-minded people today who use othering as a weapon rather than see it as a desirable trait.

I think that your point about Dracula representing a desirable “other” that we ourselves would like to be is completely accurate, and it also makes sense in the context of some of the discussions we’ve been having in class about the late 19th-century obsession with introspection and self-reflection. I’m wondering how your idea that the figure of Dracula inspires both dread and desire fits in with late 19th-century anxieties about colonialism and the foreign other. If Dracula is the foreign other that the British fear, could we also say that there is perhaps some seductive appeal to the destructive power of colonial others that the British were so anxious about?

In a way, this appears to relate back to the Longman Anthology introduction to the Victorian Age and society’s “quest for self-definition,” whether it be as a part of society, apart from society, or a combination of both as suggested in this post. On page 1068, it says that “energy of Victorian literature is its most striking trait,” and that “self-exploration is its favorite theme.” With the era being categorized as both the age of “self-scrutiny” and “reading,” these ideas are placed in combination. With that being said, I wonder if reading helped bring about this self-scrutiny you’ve discussed in your post.

I found your point about supernatural worlds vs. our own mundane worlds very interesting. Harker is out of his comfort zone and in the land of the supernatural as soon as he passes across the borders of Eastern Europe. Once he is inside Dracula’s castle, he feels like “a rat does in a trap”, suggesting that he does not enjoy his trip to the supernatural world (Stoker, 34).

From your post, I now believe that he doesn’t want to explore the supernatural world because he certainly doesn’t believe his world is mundane or that his life has too little meaning but all he has is Mina and his solicitors position. He is happy in the mundane, where he is relatively safe, and he is injured in the supernatural world that destroys his mind in a brain fever and sucks his blood. Harker does not desire to be “othered” like many of the protagonists in modern-day adaptations of Dracula.

Maia, your analysis of Dracula in correlation to popular culture is extremely thought-provoking! I find it bizarre that, often times, in order for white culture to view foreign people or concepts as appealing, it [white culture] must incorporate a sexually enticing theme or quality toward the “othered” being. It’s flabbergasting that if you were to substitute black or Japanese women in place of sexualized vampires, we would only perceive a slight shift in the methods of fetishism. This technique of deeming “othered qualities” as sexy, whilst making for a fictitious and utterly delicious read (Refer to pg. 45 of Dracula for a saucy time), also forces me to question how society exploits “mysterious” traits that deviate from the “norm.” Must we sexualize a foreign person or culture in order to appreciate its merit and validity?

The desire to be supernatural, other, the most special, is certainly rampant in today’s society. And a portion of that should definitely be attributed to the inherent and not understood desirability of supernatural characters like Dracula. But this serves to make me curious about the importance of female vampires – the succubus stories were common before Dracula, but all of the representations of the sexy vampire since Stoker’s work seem to be male. Where the female vampires at the castle not as attractive? And if that’s the case, does that underlie sexism or homosexuality on the part of the male protagonist?

It’s not only the essentially “perfect” appearance of the modern vampire that draws us in – it’s also the wealth and power that surrounds them. In nearly every vampire novel or movie that came out in the past 20 or so years, the vampire always lives in a big mansion, drives fancy cars (oftentimes more than one), and possesses a basically limitless amount of money. This modern depiction of vampirism conflicts greatly with the past, in which vampires were, as you say, “not sexy at all,” but terrifying, mutant creatures. Today, vampires represent ultimate power and freedom – they’re rich, immortal, beautiful, and the ultimate predator – basically, they inhabit the very top of the hierarchal tower. I would argue that our obsession with vampires stems from our own intimate desire for wealth and power.