Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper published their collection of poems, Sight and Song, under the pseudonym Michael Cooper in 1892. In the preface of their collection, Bradley and Cooper reveal that their poems are supposed to be “objective” reflections of art, void of subjective “theor[ies or] fancies” (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/node/228). Objectivity in poetry is difficult, however, because art in itself is interpreted by a subjective audience.

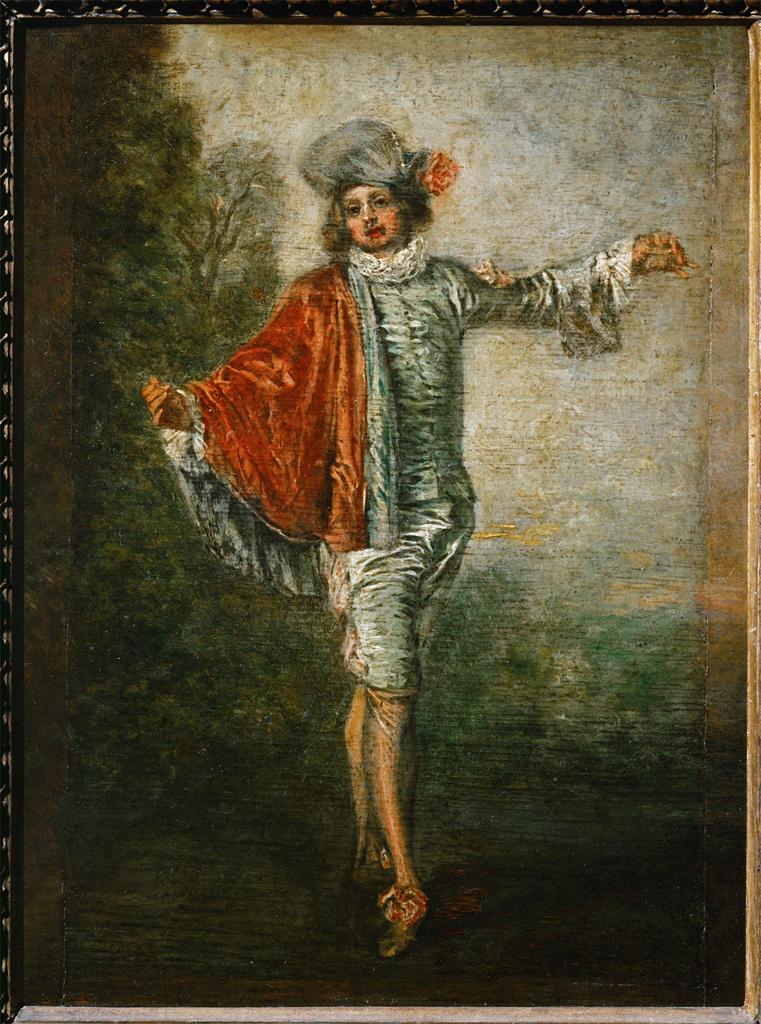

The preface of their book quotes Gustave Flaubert, who said: “Transport yourself, by mental effort, into your characters, not attract them to yourself” (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/node/228). The act of transporting oneself into a character is bound to reflect one’s own interpretation and association of people with certain actions and events. Even if Cooper and Bradley are to go “into [the] characters” of whom they write, they are going into their perception of those characters. For instance, in their poem “L’Indifférent,” they write that the boy “dances.” Since the painting displays only a snapshot of the character, Cooper and Bradley have no way of knowing whether he truly “dances,” or is simply walking or posing. Furthermore, the poets connect his presence to that of Mercury, the Roman messenger god (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/book/l-indiff%C3%A9rent). Although the Victorian Era is known to invoke mythological figures, the intentional choice to connect his “wingy hat” to Roman mythology reflects the poets’ understanding—conscious or not—that this boy is himself a messenger (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/book/l-indiff%C3%A9rent). Perhaps if other members of society had seen this painting and were writing about it, they would see the boy as a young aristocrat, not a messenger at all.

Additionally, Cooper and Bradley are caught up on the age of the “gay youngster” (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/book/l-indiff%C3%A9rent). They write that “though old enough for manhood’s bliss,/ he is a boy,/ who dances and must die” (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/book/l-indiff%C3%A9rent). Whereas another viewer might see the painting differently, Cooper and Bradley’s gaze falls on his age and mortality, leaving out, for instance, a description of the background, which is full of trees and a mix of light and shadowy colors. This could reveal another symbolic element of the painting that Cooper and Bradley are unable to convey to readers because their perspective accentuates different elements of the painting.

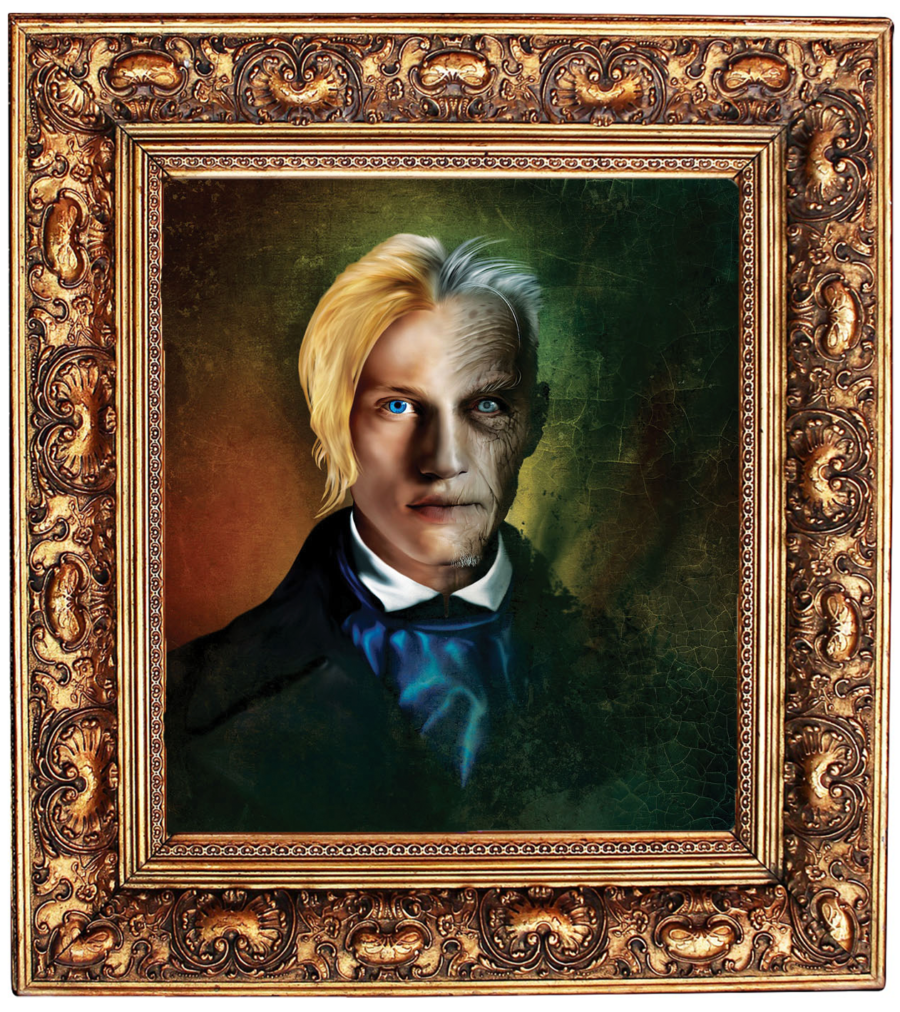

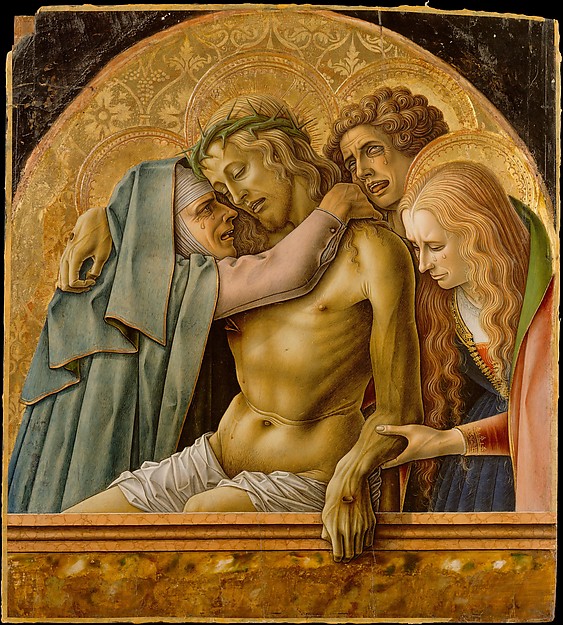

Michael Field’s other poem, A Pietà, incorporates ideas of decadence when describing Christ. The poem begins by stating: “By a swathe of the delicate, lifted skin :/ The half-closed eyes show grey,/ Leaden fissures ‘ the dead man’s face is clay” (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/book/a-piet%C3%A0).

The extremely descriptive language of “delicate” skin, and “half-closed,” “grey,” eyes around a “clay-like” face allows Cooper and Bradley to paint their own picture in the readers’ heads. This is influential because many of the readers would not have seen the painting first-hand, or if they had it would have been in a newspaper. The freedom to rewrite the painting and influence how the audience would picture its details gives Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper the liberty to put forth their own spin on the effect of the painting. They can manipulate how the audience perceives it and what the audience should take away from it. Thus, their ability to adjust the audience’s perception contradicts the preface of their collection of poems, Sight and Song, which states that art should be more than “subjective enjoyment” (https://michaelfield.dickinson.edu/node/228).