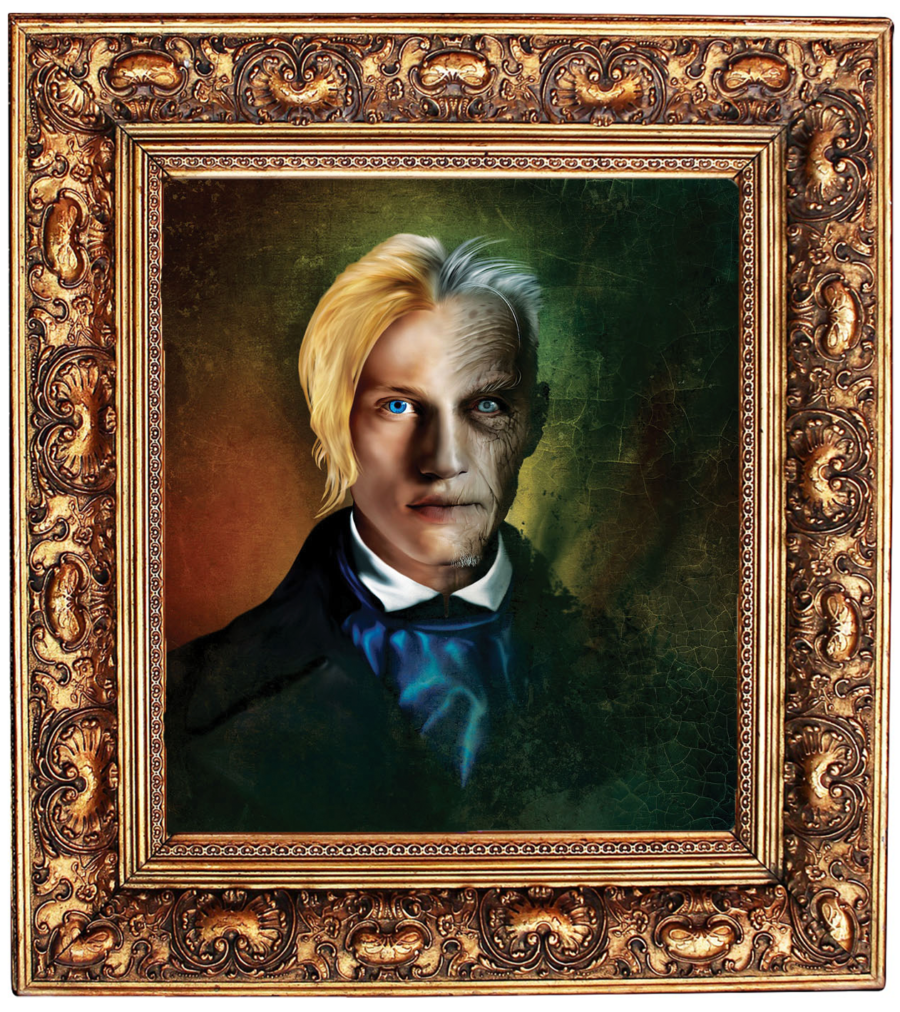

The Picture of Dorian Graydepicts both the raging aestheticism and decadence that permeated the late 19thcentury. The story centers on a painting of Dorian Gray, a young man whose beauty captures everyone’s attention. Basil Hallward, the painter of Dorian Gray, states, “he is all my art to me now…there is nothing that Art cannot express, and I know that the work I have done, since I met Dorian Gray, is good work, is the best work of my life” (16). At this point in the story, Basil describes meeting Dorian Gray and being so fascinated and enamored with his presence that he feels he must paint him in order to capture all of his beauty. Basil describing Dorian as “all my art” signifies an obsession that again revolves around Dorian’s beauty and physical appearance. Later, when Basil states that “there is nothing that Art cannot express,” he is making the claim that Art, which is what his life revolves around, is capable of capturing and expressing all things, even the indescribable beauty of Dorian Gray. Basil feels that it is his duty to paint Dorian for the sake of Art.

The idea of “art for art’s sake” that is on full display in The Picture of Dorian Gray also appears in Carolyn Burdett’s article “Aestheticism and Decadence.” On aestheticism, Burdett writes, “Art had nothing to do with morality. Instead, art was primarily about the elevation of taste and the pure pursuit of beauty” (Burdett 2014). Using this text and specific quote as a lens for The Picture of Dorian Gray,it becomes clear that Basil is an aesthete who is primarily concerned with grasping the beauties of life and reproducing it into art. Basil is not concerned with the fact that he has developed an obsession with Dorian and acts possessive over him when Harry wants to get to know Dorian as well. He was willing to destroy his masterpiece when Harry and Dorian began to argue over who got to keep the painting and asked, “what is it but canvas and colour?” (35). Basil does not fall into the category of decadence like Harry because he is primarily interested in Dorian’s beauty not the painting itself. He is solely concerned with creating a beautiful portrait of a beautiful person because that is his duty as an artist.

Lionel Johnson’s poem “The Decadent’s Lyric” can also be used as a lens for understanding The Picture of Dorian Gray. Johnson begins the poem by talking about the “very joy of shame” or the excitement gained in doing something wrong. In the novel, there is a moment when Dorian is pouring tea for Basil and Harry and is being objectified by the two men. Wilde writes, “Dorian Gray went over and poured out the tea. The two men sauntered languidly to the table and examined what was under the covers” (36). Johnson’s poem speaks to the aspect of selfishness in decadence, such as investing in expensive material items merely for their beauty as Harry does. While it is understood that it is often wrong to be selfish, decadence argues that selfishness is justified because one is appreciating beauty and art. Selfishness is enjoyable even though it is understood as shameful. In this scene, Basil and Harry are objectifying Dorian, who can be viewed as a beautiful item, as he pours the tea. While they understand that it is wrong to do so because Dorian is a much younger man and their actions could be viewed as homoerotic, the men stare at Dorian anyway because he is so beautiful. This moment is yet another example of how both decadence and aestheticism are at work in the novel.