In Professor Seiler’s Feminist Genres course, We are reading Pale Horse, Pale Rider by Katherine Anne Porter, a semi-autobiographical novella written in the stream of conscious style about the influenza epidemic of 1918. The narrator, Miranda, navigates her succumbing to influenza alongside spending her last moments with her lover, Adam, before he goes off to fight in WWI. Unlike Dracula by Bram Stoker, Pale Horse, Pale Rider is a dizzying, busy read; from Miranda’s job at a newspaper office, to rude Liberty Bond salesmen, to funerals, to rendez-vous with Adam, and finally Miranda’s fall to her recovery of influenza. Amidst the war panic, the American government is selling Liberty Bonds to raise capital for war efforts. After a conversation with the pushy Liberty Bond salesmen, Miranda decides, “Everybody was suffering, naturally. Everybody had to do his share… it was just a pledge of good faith on her part. A pledge of good faith that she was a loyal American doing her duty.” (Porter, 273) The pages about Liberty Bonds inflict a sense of nationalism as well as panic and pressure to do the right thing and be a good American, even if you don’t have money for liberty bonds like miranda. The sense of nationalism and fear is reflected in Miranda’s disease induced dream as she is in the hospital. The text states, “…Hildesheim is a Boche, a spy, a Hun, kill him, kill him before he kills you…” (Porter, 309) Here, Hildesheim is Miranda’s doctor, however the atmospheric chaos of the disease and war cause Miranda to be paranoid of her German doctor, hence the terms used in the text and at the time in history “Boche” and “Hun,” both terms that have a negative connotation of a person from outside American, especially during WWI. To add to the atmosphere of disease, Miranda often comments on her dis-ease, for example, “‘There’s something terribly wrong,’ she told Adam. ‘I feel too rotten. It can’t just be the weather, and the war.’” (Porter, 282) In this quote, Miranda acknowledges both fictional atmosphere; the weather, and the tonal atmosphere; influenza and the war. The atmosphere of the novella is that of illness and war panic, and overall dis-ease and discomfort on behalf of Miranda. The same can be said of Dracula.

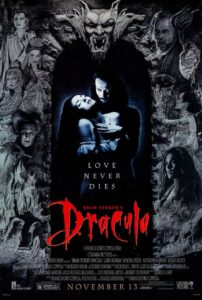

In Dracula, the disease and the threat to nationalism is symbolized through the vampires which creates the atmosphere of dis-ease and fear among the British men. It is a known fact that vampires bite the necks of their victims and suck their blood. A classmate brought up the sexual undertones of this action; thinking about biting, sucking and transmitting disease which can be seen as actions of a fictional character or that of sex. Throughout the novel, vampires are referred to as “monsters” and “evil,” making them outsiders to the group of (mostly) British white men, plus Mina and Lucy. Viewing the Transylvanian, non-British vampires as outsiders is xenophobia. Of course, Dracula is the main outsider, however, in A Capital Dracula Franco Moretti makes the argument that Morris, The American, is an “accomplice” to Dracula and possibly a vampire himself, therefore has to die in the end. Moretti points out Morris is the first character to use the word “vampire” (chapter 21). Moretti writes, “To make Morris a vampire would mean accusing capitalism directly: or rather accusing Britain, admitting that it is Britain herself that has given birth to the monster.” (Moretti, 436) In other words (ignoring Moretti’s analysis of capitalism and focusing on xenophobia/nationalism), assuming Morris is a vampire, Britain would take the blame because, even though Morris is not British, he was in the country and able to breed more “monsters,” possibly as an extension of Dracula according to Moretti. This spreading of vampirism/disease by Morris is demonstrated by the blood transfusion from Morris to Lucy, which Moretti claims possibly caused Lucy’s change into a vampire, which created dis-ease among the men. Although the transmission is not through sexual biting or sucking, the disease of vampirism is spread via blood, similar to a sexually transmitted disease. Even though Morris is a white male from America, he is the foreigner friend of the British group of men, therefore there is still a sense of xenophobia and dis-ease, as Morris is the only man out of the group to die, furthering the theme of British nationality in Dracula.