She walks / in beau/ty, like / the night (8)

Of cloud/less climes / and star/ry skies; (8)

And all / that’s best / of dark / and bright (8)

Meet in / her as/pect and / her eyes; (8)

Thus mel/lowed to / that ten/der light (8)

Which hea/ven to gau/dy day / denies. (9)

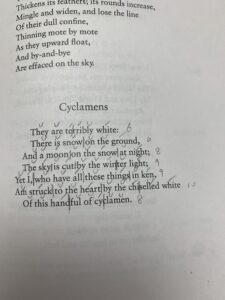

I guess it’s the sounds in Michael Field’s “Cyclamens” that reminds me of the first stanza of “She Walks in Beauty.” What first struck me about Michael Field’s poetry is the intimacy in the poetic voice, which is quite absent in many of the love poems written from the male lover’s prospective (thinking of Romantic and early modern poets). There are a lot of factors at play in regard to this difference, but I would like to focus on meter in this blog post. I have given my scansion on both texts. “She Walks in Beauty” is in iambic tetrameter, so it consists mostly of iambs. While “Cyclamens” consists of both iambs and anapests. Iambs have a skippy rhythm like the beat of a song, which serves the purpose of the poet praising, idolizing the beloved. Mixing anapests with iambs, “Cyclamens” reads more like natural speech. This poem resists patterns and regularity. Anapests do not give the satisfaction of balance and rhythm like iambs. The rhymes also seem casually in place. There is not a clear rhyme scheme. This poem is inching towards free verse.

By rejecting regular metrical and a rhyme scheme, “Cyclamens” is rejecting the idealization of the beloved and stating that such idealization does not truly capture human intimacy. Byron’s beloved contains “all that’s best of dark and bright,” has the tenderness of “cloudless climes and starry skies.” But there’s a bit of tension, even violence in “Cyclamens.” The flowers are “terribly white,” “chiselled white”; the sky is “cut” by the light. And the speaker is unimpressed by what Byron praises, the sky, the moonlight, the snow. The lines become longer as the poem goes on except for the last line, as if purposefully refusing to give any closure.