The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was an initiative begun in 1933 by Franklin Roosevelt as part of the New Deal. The Great Depression, which began with the crash of the stock market in 1928, was one of the most tumultuous periods in American history. As businesses and banks closed, over ⅓ of the US population became unemployed, creating a national crisis. President Roosevelt created the New Deal to give jobs and opportunities to the newly unemployed, including the creation of the CCC. While the program mainly intended to provide work, it also began a conservation movement in America’s parks and forests that involved everyday citizens.

Undated photograph of Camp S-51-PA in the winter. A large building, perhaps the Mess Hall, is in the foreground, and the barracks behind it. Source: http://www.schaeffersite.com/michaux/#CCC

The area we are studying in Camp Michaux was designated Camp S-51-PA, which indicated it was on state land. At the time, it was referred to as either Pine Grove Furnace Camp or South Mountain Camp, in reference to the known features of the region. It was one of the first CCC camps opened, and soon housed 200 men seeking work. Their first project was to construct the buildings, which survived for the next several decades. While most of the campers worked on this, the first small crew was sent out to work on improving the road to the Baker sawmill on June 1, 1933. By Christmas of 1933, the barracks were finished and the campers and officials could move in.

An undated photograph of the young CCC men at Camp Michaux, then known as Camp S-51-PA. Source: http://www.arcse.org/qCCCboys.htm

Over the course of nine years, the men did numerous jobs to restore and preserve Michaux Forest and Pine Grove Furnace State Park. They built access roads, including the one used to reach the site today (Michaux Road), planted trees, strung telephone wire, and fought fires. They also built and improved upon the camp themselves, constructing more than forty buildings on the site. As Camp Michaux was a residential site, there were many activities aside from work in Michaux forest. The men published a weekly newspaper, participated in baseball leagues, and even had opportunities to earn high-school degrees. The camp not only gave the men immediate job relief, but also set them up for a more successful future. The camp closed in 1942 when World War II began, and the economy was resurrected with industrial demands from overseas, such as steel, machinery and weaponry.

The fountain, believed to be constructed by the CCC, as it looks today. Source: http://www.schaeffersite.com/michaux/history-dave-smith.htm

There is more to learn about the CCC from Camp Michaux. Our archaeological research here hopes to find clues that will answer some questions we have about this period of Camp Michaux’s history. While historical records and photographs form the basis for most of what we know so far, we hope to gain better insight and paint a clearer picture to help tell the story of Camp Michaux.

To do this, some of the questions we are asking are:

- What was day-to-day life like as a CCC camper here? How did they work, play, and eat?

- How did the CCC affect the reforestation of the Michaux forest and South Mountain? What archaeological traces can we find of this initiative?

Daily activities usually leave a trace – some things are dropped and forgotten, others are thrown away. We may expect to find glass objects like bottles, nails, and other metal objects like tools and cans. It may also be possible for us to find personal effects from the men, such as hair combs or dog tags, that could tell us who they were or where they were from. From these artifacts and the foundations of the camp buildings we can piece together what CCC life was like. Additionally, the CCC was one of the first instances of large-scale, federally funded conservation, and there is an important link between the archaeology of the site and the history of conservation in the area. By documenting the ecology, we can learn what parts of the forest were affected by the CCC and use those areas as places to perform potential archaeological surveys.

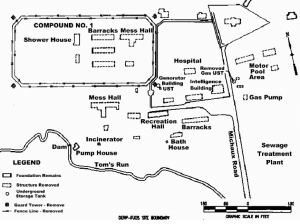

Using a database called GIS, which stands for Geographic Information Systems, archaeologists can examine the landscape of an area such as Camp Michaux to identify important natural resources. We can use aerial photographs to physically see the affect the CCC had on Michaux forest, such as where the buildings were constructed and which parts of the forest became denser from planting trees. Also part of this database are Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), which can show us faint traces of structures on the ground that other tools may not be able to see. With the tools in the database and ground survey techniques, it is possible to paint a picture of everyday life at Camp Michaux almost a hundred years ago.

Useful Sources

Bland, John Paul

2006 Secret War At Home: The Pine Grove Furnace Prisoner of War Interrogation Camp. Cumberland County Historical Society Heritage Publications, Carlisle. Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania Conservation Heritage Project

http://paconservationheritage.org/stories/the-civilian-conservation-corps-ccc-1933-1942/

Speakman, Joseph

2006 At Work in Penn’s Woods. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Smith, David L

2010 Camp Michaux Home Page, The History of Camp Michaux, http://www.schaeffersite.com/michaux/history-dave-smith.htm, accessed 3/6/2018

Smith, David L

2014 William V. and George F. Garner Digital Library, Camp Michaux Historical Site,

http://gardnerlibrary.org/encylopedia/camp-michaux-historical-site, accessed 3/6/2018

Created by Olivia Ellard and Marc Morris