Stephen M. Norris, Miami of Ohio

In 2015, Russian President Vladimir Putin finally went on record about what happiness meant. When a reporter had asked him two years earlier whether or not he was happy, the President could not answer, stating instead that the question was a philosophical one for which he could not provide a concrete response [http://www.gazeta.ru/social/news/2013/04/25/n_2875989.shtml]. Two years later, Putin had figured it out. When asked the very same question, he replied that “happiness is in the possibility of doing something you love and achieving outstanding results [shcast’e v vozmozhnosti zanimat’sia liubimym delom i dobivat’sia vydaiushschikhsia rezul’tatov].” [http://www.gazeta.ru/social/news/2015/05/21/n_7216085.shtml]

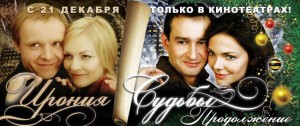

The question of happiness is also one taken up by one of the most popular films in the last decade, Timur Bekmambetov’s 2007 sequel to El’dar Riazanov’s 1976 classic, Irony of Fate [Ironiia sud’by, ili S legkim parom!]. Irony of Fate: The Continuation [Ironiia sud’by. Prodolzhenie] was released for New Year’s 2008 and cleaned up at the box office, setting a then-record by earning $49m. The film cemented Bekmambetov’s place as one of the most important filmmakers of the 2000s. It also engaged in a dialogue about happiness across the decades, spanning the Brezhnev era to the Putin era. In Bekmambetov’s film, Putin made an appearance and proved much better at defining happiness than he did when asked a few years later. The plot in Irony of Fate: Continuation reveals that the Putin era provides the possibility for happiness while the Soviet era did not.

The two films both take place on New Year’s Eve. In the original, a doctor, Zhenya Lukashin, is planning to propose to his girlfriend. In a discussion with his mother, he notes that he is 36 years old and fears that he might never get married. He plans to pop the question to Galya, his younger girlfriend, that night. First, however, he goes to his annual banya visit with his friends. Although he pleads that he cannot tolerate alcohol, his friends persuade him to take a few shots to celebrate his impending engagement. Soon all are inebriated and Zhenya winds up on a plane to Leningrad. Unaware upon arrival that he is in a different city, he asks a taxi driver to take him to his address: 25 Third Builder’s Street, Apartment 12. His key works. He crashes on a bed, only to find out that a beautiful woman, Nadya, lives there. It turns out that she was preparing for a New Year’s proposal from her boyfriend, Ippolit. Over the course of the night, Zhenya and Nadya fall in love. At the end, after Zhenya has returned to Moscow, he awakes and finds Nadya in his apartment.

Riazanov’s film suggested the possibility of happiness in the Brezhnev era, but left the ending ambiguous about whether or not the two protagonists found it. Irony of Fate teases viewers throughout with the idea that happiness is not an inalienable right in the USSR. In Kul’tura, A. Makarov wrote that the film captured a certain worldview prevalent at the time: “Look closely: these are typical losers, victims of all that is dull and Soviet, people who more than anything else fear happiness (qtd in MacFadyen 221).” Throughout the film, happiness is set up as an almost unattainable quest. Zhenya and Nadya, when they think about their marriage prospects, wonder if they can even find happiness at their age. A drunk Ippolit wonders aloud whether “there can be such a thing as a programmed, expected, planned happiness,” before answering “no.” When Nadya arrives in Moscow, it seems as though she and Zhenya have found happiness. She asks Zhenya’s mother is she is being frivolous. The mother responds, “We shall see.”

Bekmambetov’s remake takes up this closing statement. Irony of Fate: Continuation occurs three decades after the original. In it, viewers learn that Zhenya and Nadya did not marry and did not find happiness. Nadya went back to Leningrad, married Ippolit, and had a daughter (also named Nadya). Zhenya had a son, Kostya. As Arlene Forman has written in her review of the sequel [http://www.kinokultura.com/2008/22r-irony.shtml], “Bekmambetov’s revisionist remake denies the possibility that intimacy, love, and personal fulfillment could have existed in the Soviet era.” Despite the fact that Nadya and Zhenya have the right sort of values, the right sort of jobs (he is a doctor, she is a teacher), and the right outlook on life, happiness just was not possible in the Soviet Union.

It is possible in the post-Soviet Russia of Vladimir Putin. Irony of Fate: Continuation’s plot essentially follows that of its predecessor. Kostya, a doctor like his father, visits the banya on New Year’s Eve. His dad’s pals tell him the story of 30 years before. They get Kostya drunk despite the son’s protestations that he too cannot tolerate liquor, and pack him off to Petersburg. Kostya enters Apartment 12, 25 Third Builder’s Street. Nadya’s daughter, also a teacher, lives there. She is about to marry Irakly, a snarky cell phone salesman who cares more about business and his car than his would-be fiancée. Over the course of the night, Kostya and Nadya fall in love. This time their happiness is granted.

This cross-generational, three-decades-long cinematic dialogue about happiness concludes when Zhenya shows up in Petersburg and expresses his regrets for what happened in the 1970s. “I don’t know about you,” he states, “But I had happiness in my life. … Happiness is not like a sickness, it can’t just go away. If it’s given to a man then it’s given forever and it always protected me in my life. This happiness is like armor to me.” Ippolit, we learn from Nadya, never had happiness and has tried to ruin it for others. This time around, she returns with Zhenya to Moscow for good. Fathers and sons, mothers and daughters can all find happiness now.

It’s a possibility, Irony of Fate: Continuation makes clear, that can only happen in Putin’s Russia. Zhenya’s and Nadya’s values, particularly those associated with holding a good job, searching for true happiness in life, and not being overly concerned about material life, have survived the Soviet experiment and been passed down to their children. President Putin appears in the film delivering his New Year’s Address. He notes that the holiday is a time for looking back on the past and remembering it, but also a time to look forward to the future and what it might deliver. Putin’s remarks provide the answer to happiness that he was unable to provide to the interviewer in 2013. In the end, happiness is about not thinking too much about the past and instead focusing on the relations you have with your family and your loved ones. And it’s all brought to you by Putin.

July, 2015

Works Cited:

Forman, Arlene. “Timur and His Gang Strike Back.” KinoKultura 22 (October 2008): http://www.kinokultura.com/2008/22r-irony.shtml.

MacFadyen, David. The Sad Comedy of El’dar Riazanov: An Introduction to Russia’s Most Popular Filmmaker (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003).