In order to completely answer our team’s question (is there a meaningful connection between World War I and the expression of poetry published during the same time?), we had to observe nature-driven poems from before and after the war and compare the data with “In Flanders Fields” and to each other. Our team ultimately chose this particular question due to our interests in symbolism of nature, and its expression in poetry. We desired to understand if major historical events had any impact on nature poetry from that era, and we decided World War I would be the best historical event to choose due to its resulting damage to nature. Our team hoped to discover that there was a correlation to World War I and a negative symbolism of nature in poetry. As a whole, we hoped to discover that there exists a direct correlation between a positive or negative historical event and a positive or negative expression of nature in poetry, respectively. To see this trend, as stated earlier, we must observe poetry with natural elements before and after The Great War.

After selecting a random sample of ten poems from before the war and ten from after the war, we asked our computer science team to calculate the number of lines in each poem, the number of words in each poem, and the number of distinct, or unique, words in each poem. The results can be observed in the chart below:

| Poems | Number of Lines | Number of Words | Number of Distinct Words |

| “The Darkling Thrush” | 32 | 160 | 108 |

| “The Garden of Proserpine” | 96 | 519 | 220 |

| “The Panther” | 12 | 91 | 61 |

| “The Treasure” | 14 | 97 | 68 |

| “A Shropshire Lad” | 1414 | 8409 | 1850 |

| “Adlestrop” | 16 | 93 | 59 |

| “In the Desert” | 10 | 49 | 24 |

| “The Wild Swans at Coole” | 30 | 174 | 92 |

| “The Graveyard by Sea” | 144 | 1095 | 439 |

| “At Night” | 8 | 81 | 51 |

| “A Minor Bird” | 8 | 66 | 44 |

| “February Twilight” | 8 | 43 | 26 |

| “Nothing Gold Can Stay” | 8 | 40 | 27 |

| “Spring and All” | 27 | 140 | 75 |

| “Spring” – Edna St. Vincent Millay | 18 | 109 | 64 |

| “Spring” – Henry Gardner Adams | 12 | 63 | 45 |

| “Tell Me Not Here, It Needs Not Saying” | 30 | 174 | 113 |

| “The Seed Shop” | 12 | 96 | 61 |

| “The Waste Land” | 440 | 3012 | 826 |

| “The Woodpecker | 8 | 72 | 35 |

| “In Flanders Fields” | 15 | 97 | 59 |

Figure 1– The collection of data received from the computer science team. The results above include the number of lines, words, and distinct words each poem selected. The first ten poems were the ones published before the breakout of World War I, the next ten were published after the war, and the last poem written during the war.

With the results from figure one, the Number of Lines column and the Number of Words column can be placed into a couple of bar graphs separately published before, during, and after the war that can be seen below:

Figure 2: The line and word count of nature-drive poems are visualized in this bar chart.

Figure 2: The line and word count of nature-drive poems are visualized in this bar chart.

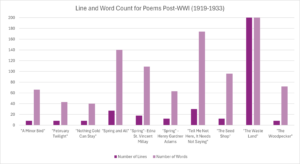

Figure 3: The line and word count for nature-driven poems that were published after the war.

Figure 3: The line and word count for nature-driven poems that were published after the war.

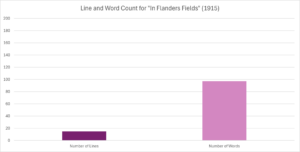

Figure 4: The line and word count for “In Flanders Fields” which was published during World War I

Figure 4: The line and word count for “In Flanders Fields” which was published during World War I

In observing both quantitative categories of bar in Figure 2 and 3, overall, there exists a slight drop in line count and a drop in word count for the poems after World War I compared to the poems prior. From Figure 3, the number of lines for almost all the poems (except “The Waste Land, this is an outlier), remains thirty or under. However, in observing the same topic in Figure 2, only six poems out of the ten remain thirty lines or under. Now, in regards to the Number of Words category, the number of words, average number of words (just from observing the charts) drops significantly after the war. The majority of poems from Figure 2 have over ninety words, except for two (“In the Desert” and “At Night”). However, in Figure 3, you can see that half of the poems do not even reach ninety words.

Additionally, our team wanted to reflect on the Type Token Ratio (the ratio of the summation of unique words over the number of words) of each poem to support our findings from Figure 2, 3, and 4. The results can be found below (rounded to the third decimal place):

| Poem | Type Token Ratio |

| “The Darkling Thrush” | 0.675 |

| “The Garden of Proserpine” | 0.424 |

| “The Panther” | 0.670 |

| “The Treasure” | 0.701 |

| “A Shropshire Lad” | 0.220 |

| “Adlestrop” | 0.634 |

| “In the Desert” | 0.490 |

| “The Wild Swans at Coole” | 0.529 |

| “The Graveyard by Sea” | 0.401 |

| “At Night” | 0.630 |

| “A Minor Bird” | 0.667 |

| “February Twilight” | 0.605 |

| “Nothing Gold Can Stay” | 0.675 |

| “Spring”- Edna St. Vincent Millay | 0.536 |

| “Spring” – Henry Gardner Adams | 0.587 |

| “Tell Me Not Here, It Needs Not Saying” | 0.714 |

| “The Seed Shop” | 0.649 |

| “The Waste Land” | 0.274 |

| “The Woodpecker” | 0.486 |

| “In Flanders Fields” | 0.608 |

Figure 5: A chart showing each poem and their corresponding Type-Token Ratio

Not much can be viewed from the chart so we decided to visualize these data findings as well which can be observed below:

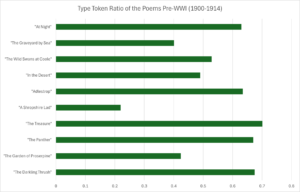

Figure 6: The Type-Token Ratios of the poems published prior to World War I

Figure 6: The Type-Token Ratios of the poems published prior to World War I

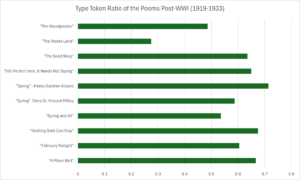

Figure 7: A bar chart visualizing the Type-Token Ratio of nature-drive poems published after World War I.

Figure 7: A bar chart visualizing the Type-Token Ratio of nature-drive poems published after World War I.

Figure 8: The Type-Token Ratio of “In Flanders Fields”

Figure 8: The Type-Token Ratio of “In Flanders Fields”

As you can see from Figure 6 and 7, the majority of poems’ Type-Token Ratio falls between the numbers 0.4 and 0.7 where the prior poems contain one outlier while the post poems contain two. The Type-Token Ratio of “In Flanders Fields” also falls within the same range. However, it can be observed there is more fluctuation between the range in Figure 6 than in Figure 7.

Our team hoped to find a correlation between the historical event of World War I and its effect on the view of nature. We hoped we would be able to find substantial conclusions to our wonders, but no conclusion could be made about correlation from the results of our data. In utilizing the data for line and word count, we believed that there would be drastic change for one way or another between the poems before and after World War I. We had hoped that the numbers would comment on the intensity, and in using our analysis from “In Flanders Fields,” we could make a final conclusion. However, there was not a significant amount of change between the numbers that a meaningful conclusion could be made. It is true that there was an overall drop in line and in word count in the post-WWI poems compared to the pre-WWI poems, but this drop was not significant enough to attribute an intensity change, and hence, correlation.

Finally, we wanted to observe the variation in word usage in every poem we selected. Our team hoped to see that if there was a higher variability of post-WWI poems, then more topics were talked about which would support the main message of the poem more. Thus, more variability, more intensity. If there was a change in the Type-Token Ratio between pre-WWI poems and post-WWI, then we would approach it the same way we wanted to with the line and word count: tie the results back to the analysis of “In Flanders Fields” and make a conclusion on if World War I had a positive or negative impact on views of nature in poetry. Unfortunately, like the data for line and word count, there was no substantial change between the poems before World War I and the poems after the war. In fact, both groups’ Type-Token Ratio fell between the same numbers (excluding a few outliers) which means the number of different topics discussed in each poem are around the same number.

Our group concluded that with the results we obtained from distant reading that the evidence collected does not support a correlation between World War I and the expression of nature in poetry. Because the results for both distant reading observations (the line and word count and the Type-Token Ratio) remain consistent through different war eras, it appears the events of World War I had no impact on expression of nature in poetry, whether it be positive or negative or the intensity of the subject. This counteracts what our team initially believed, which was that there was some type of positive or negative correlation. There appears not to be one.