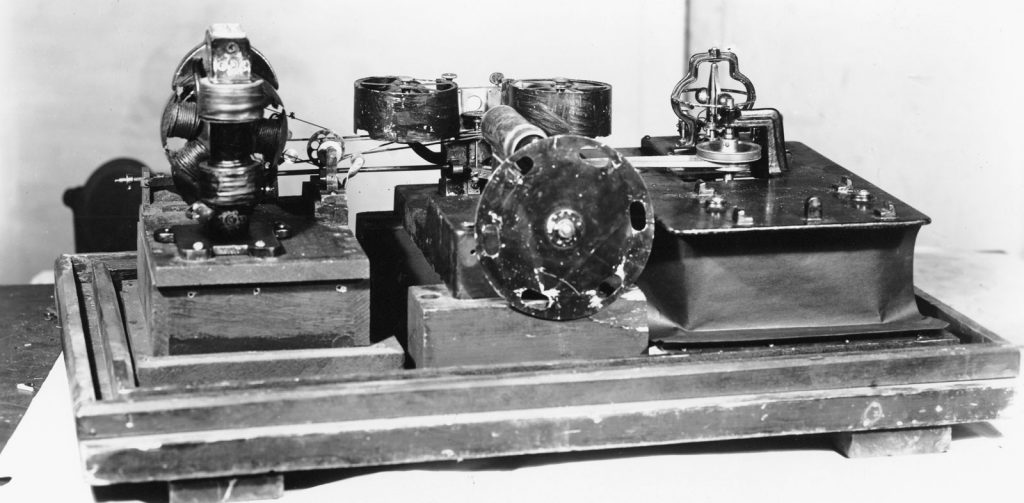

Thomas Edison and his employee, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, were credited for making many new inventions in filmmaking during this era. They created both the kinetoscope and the kinetograph. The kinetoscope was a four-foot-high box that played film reels on a loop.[1] The viewers paid a nickel to watch a film through the box’s lens peephole. [2] The kinetograph was the first film camera, which used 35mm film. Both Edison and Dickinson created many films, using the kinetograph, at Edison’s studio in West Orange, New Jersey. [3] These films include Dickson Greeting, Men Boxing, Duncan Smoking, and many other shorts.[4] However, the films were only shown at exclusive events. For example, Dickinson Greeting, which was filmed in 1891, was only shown to members of The Women’s Club of America.[5]

Edison’s Kinetograph. Photo Courtesy from Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/Kinetograph#/media/1/318205/97822

The first kinetograph film publicly shown was Blacksmithing Scene on May 9, 1893, at an event at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.[6] The success and popularity of the kinetograph grew throughout the US over the next year as evidenced by the story told by Edison’s secretary, Al Tate. On Saturday, April 14th, 1894, Tate, along with his brother and Tom Lombard; who worked for the Chicago Central Phonograph Company, were tasked to set up the kinetoscope parlor to ensure it was ready for its opening on Monday. They finished around 2 pm and planned to celebrate by going to Delmonico for dinner. However, Tate noticed the number of people standing outside of the kinetoscope parlor and had an idea.[7] He told his brother and Mr. Lombard “‘why shouldn’t we make that crowd out there pay for our dinner tonight.’”[8] So, they decided to open early and planned to be finished by 6 pm. They thought by 6, they should have enough money to pay for dinner. However, due to the number of people there, the three of them sold about 500 tickets and did not close until 1 am.[9] The parlor was a huge success and Edison later wrote to the Holland Bros., who owned the parlor, that “‘I am pleased to hear that the first public exhibition of my Kinetoscope has been a success under your management, and hope your firm will continue to be associated with its further exploitation’”[10]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cm5g7CfXYYE

This parlor was the first time that the kinetoscope was available for mass consumption. The films shown at the parlor were some of the first films to be publicly consumed. They were ten films totaled available to watch; one of them being Blacksmithing. The other films were Sandow, Roosters, Bertoldi (Mouth Support), Bertoldi (Table Contortion), Horse Shoeing, Trapeze, Wrestling, Barber Shop, and High-land Dance. [11] For those who are confused with Sandow and Bertoldi, the title referred to the names of people. Eugen Sandow was a German bodybuilder and the film shows him flexing his body.[12] Ena Bertoldi was a contortionist and the films showed her performing her acts.[13]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QWLDe31ni_E

When people think of films today, they don’t imagine sticking their face into a pair of goggles, attached to a wooden box. Nowadays, films can be watched anywhere and anytime. They are even companies now, like Quibi, that make content solely to be watched on phones. Even though the means of watching films are ever-changing, when people ask, “what was the first film”, they may be asking “what was the first film in the theater?” To answer that, the question “what was the first theater?” should be answered first.

Banner Photo Courtesy from the American Society of Cinematographers. https://theasc.com/asc/asc-museum-kinetoscope

[1] Andre Gaudreault, ed., American Cinema 1890-1909: Themes and Variations (Chicago: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 7.

[2] Paul Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 299.

[3] Gaudreault, American Cinema, 24.

[4] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 210.

[5] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 212.

[6] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 296; “National Film Preservation Foundation: Blacksmithing Scene (1893),” National Film Preservation Foundation: https://www.filmpreservation.org/preserved-films/screening-room/blacksmithing-scene-1893.

[7] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 309; Gaudreault, American Cinema, 23.

[8] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 309.

[9] Gaudreault, American Cinema, 23.

[10] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 309.

[11] Deac Rossell, “A Chronology of Cinema, 1889-1896,” Film History 7, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 127.

[12] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 325-327.

[13] Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies, 328.