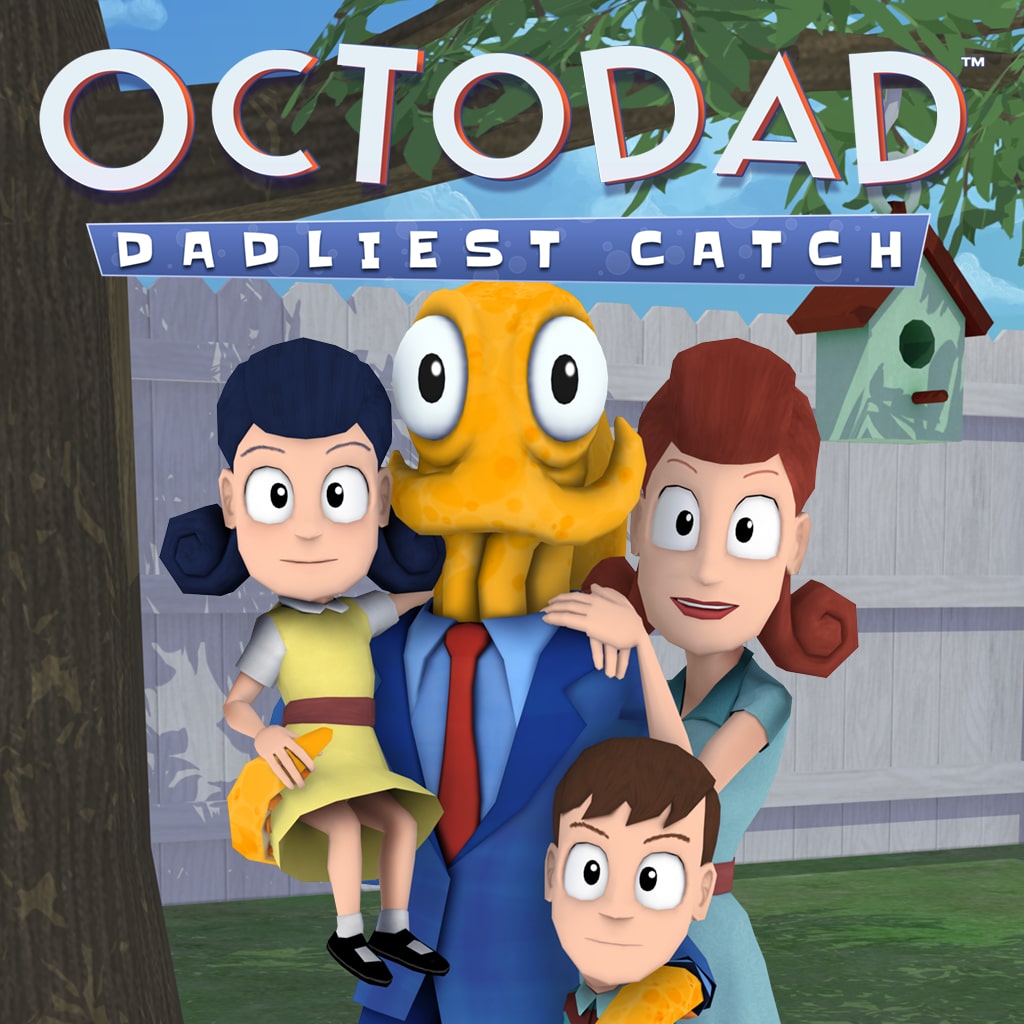

In 2014, indie video game company Young Horses released Octodad: Dadliest Catch, perhaps the most unusual stealth game of all time. The game enables the player to assume the role of Octodad, an octopus not-so-subtly masquerading as a human husband and father. To the player, Octodad immediately stands out as an octopus. His bright yellow skin, suction-cup hands, and tentacle mustache hardly constitute humanoid features. However, the other characters in the game world seem entirely ignorant of Octodad’s performance. His wife lovingly kisses his tentacles without recoiling, and he inexplicably produces two human offspring with no cephalopodic features. As the game’s theme song proclaims, “Nobody suspects a thing.”

Game studies scholar Bo Ruberg suggests that Octodad can be broadly read “as a video game about ‘passing’” (85). Queer theorists can read Octodad “as a queer subject struggling to pass as cisgender or straight” (102). Critical race theorists can interpret Octodad as “a racialized other—a person of color who must pass as an acceptable subject within a social system that believes that being normal and successful means being…white” (102). Meanwhile, disability studies theorists can analyze Octodad’s bodily differences. After all, “Octodad must quite literally contort his body to fit the design of the world around him” (102). In addition to these rich interpretations, I suggest that Octodad allows the player to act out the theatrics of gender performativity. Like drag, the game exaggerates the rigidity of gender roles in order to subvert and satirize them. Through the use of mechanical storytelling and unwieldy controls, Octodad offers a critique of gender performativity that could only be conveyed in the video game form.

The setting of Octodad evokes the hauntingly heteronormative suburbia of 1950s America. Octodad’s home is quite literally enclosed by a white picket fence. His beautiful garden thrills with primary colors, complete with a seesaw for his daughter and a shed full of sports equipment for his son. Inside the home, Octodad’s wife works in the kitchen, washing dishes at a mint-colored sink. The cephaloprotagonist’s four-person household perfectly imitates the nuclear family. As the head of this unit, Octodad must fulfill a set of gendered expectations. But how is Octodad to know what gendered actions to perform? With no prior experience being a human man, Octodad must imitate the human men that surround him.

In Gender Troubles, Judith Butler argues that humans imitate gender just as much as octopuses. To Butler, gender identity is nothing more than “a set of imitative practices which refer laterally to other imitations and which, jointly, construct the illusion of a primary and interior gendered self” (188). In other words, gender is an imitation of an imitation. Humans do not act out gender performatives because it is in their nature to do so. Instead, they copy other humans to assimilate into normalcy. As an octopus, Octodad emphasizes this mimcry. He does not contain an “interior and organizing gender core” (Butler 186). Rather, he imitates the media he consumes, the neighbors he encounters, and the expectations of a strange society. “Like the two stubby tentacles that make up his pseudo-manly mustache,” writes Ruberg, “Octodad’s gender is clearly a construct cobbled together from tropes” (96). Like the perfect American father of the 1950s cultural imagination, Octodad must brew coffee for his wife and flip burgers for his children. He mows the lawn and weeds the garden like his neighbors. He even forces his body into a three-piece suit to look like society’s ideal businessman. At every point, however, the game renders these heteronormative rituals farcical. Due to the difficult control schema, it is almost impossible to accomplish any of these tasks “naturally.” Octodad spills coffee beans, hurls burgers in the air, tramples flowers, throws mowers, and trips over—well, just about everything. The game’s ridiculousness implicitly reveals the performativity of these gendered rituals. Some may “come to believe” their own gender performance, but this does not make it any more innate or natural (Butler 192). Like Octodad’s suit, gender is a “thin veneer” that allows humans to function within a heteronormative society (Ruberg 96). “For Octodad,” though, “the clothing truly does make the man. Beneath it, there is only octopus” (96).

Throughout the game, Octodad must navigate various obstacles all while maintaining his humanlike demeanor. Many levels are reminiscent of early slapstick comedy. For instance, Octodad must dodge banana peels in the supermarket and avoid puddles aboard a ship. These challenges may seem low stakes, but they all spell doom for Octodad. If he gets found out, he may be killed by a chef or, even worse, rejected by his newfound family. The player fails a level if the game’s “Suspicion Meter” rises too high. If Octodad crashes into furniture or careens into bystanders, people begin to suspect his performance. Once the meter rises too high, the player is forced to begin the level again from the beginning. Gender, Butler argues, is constructed by “a reenactment and reexperiencing of a set of meanings already socially established” (191). In other words, “gender requires a performance that is repeated” (191). In Octodad, the constant repetition of levels as players fail and then try again epitomizes the construction of gender. If players do not perform as a convincingly heteronormative man, they must attempt their tasks over and over. When they finally complete the level, they will have repeated it so many times that they have truly mastered the performance of masculinity. The usually nondiegetic function of game failure serves a narrative purpose. Mastery in the game equals a mastery of gender. Players “quite literally play at heteronormativity” (Ruberg 85).

The nondiegetic function of the meter also presents an intriguing social critique in itself. Though Octodad’s wife and children never grow suspicious of him, the Suspicion Meter remains visible even when he is at home alone with them. A dotted line always connects their line of sight to his body, demonstrating how Octodad tracks their shifting eyes. He anxiously awaits the day his ruse will be up, his identity exposed, even among those who love him most. This implies an internalized panoptical gaze; even when prying eyes are not watching, Octodad still acts in accordance with society’s rules. An “interior psychic space” has been “inscribed on the body” by society’s gendered expectations (Butler 135). Octodad cannot escape the gaze because it lives within him.

Perhaps most interestingly, the game invites the player to recognize the ridiculousness of their own gender performance through the use of unwieldy controls. “The game celebrates a kind of queer, distinctly non-normative movement” through both the actions “seen on-screen” and “in the physical inputs of the player” (Ruberg 93). One does not master the controls of Octodad. Rather, one barely scrapes by, moving from level to level with extreme difficulty. The game has spawned countless rage compilation videos on YouTube and other social media platforms. Still, the game’s difficulty can and should be read as more than rage bait. Octodad’s “embodied controls” do not simply “represent difference” (85). Instead, they allow “players to inhabit that difference” (85). The game refuses to adopt any traditional control schema. Each of Octodad’s limbs must be moved individually by a different button, rendering even “a supposedly simple act like walking” absurd (91). The odd movements of Octodad’s legs mirror the unusual motions of the player’s thumbs. As Octodad struggles, so does the player, forcing them to reassess the control inputs they previously deemed “natural” or “intuitive.” Implicitly, then, the game calls the player’s own body into question. Is their own gender performance seamless, or does it involve just as much stumbling as Octodad’s? Are the actions they perform natural, or have they been learned like the buttons on a controller? What makes them all that different from an octopus desperately trying to convince everyone around him that he is a real, genuine man? Through controls alone, the game suggests that the player may have more in common with Octodad than they initially supposed.

Octodad: Dadliest Catch presents a humorous yet harrowing portrayal of gender performance. Through nondiegetic functions like game failure and the Suspicion Meter, the game demonstrates how gender is constructed through repetition and internalization. Meanwhile, the difficult controls call attention to the player’s own shoddy gender performance. Despite its levity, the game also makes room for genuine empathy. Octodad struggles to fit into impossible boxes like countless queer humans before him. One does not need to dive into the sea to spot a fish out of water; one needs only step out the front door.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 2007. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=d47e680a-1ff8-3819-96b2-0b70dd97b01c. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.

Octodad: Dadliest Catch. Directed by Kevin Zuhn, Young Horses, 2014. Sony PlayStation 4 game.

Ruberg, Bo. Video Games Have Always Been Queer. New York University Press, 2019, doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479893904.001.0001. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.