https://www.wevideo.com/view/3925063595

Intro

Since the birth of democracy in the United States, immigrants have made significant contributions to the ever-evolving American identity. At the age of 34 in 1883, American poet Emma Lazarus was aware of this fact yet existed in an era of xenophobic nationalism in the United States. To combat this wave of intense loathing towards foreigners, Lazarus composed a literary work that would forever be engrained in American poetry. In her poem, “The New Colossus,” Emma Lazarus conveyed her view of America as being a sanctuary for immigrants escaping oppression. By comparing the traditionally masculine image of power associated with the Colossus of Rhodes with a maternal guardian, and through her use of imagery of light as a symbol of hope, Lazarus challenged the classical notions of strength and redefined national identity around refuge and the embracement of immigrants, which contrasted the common value of hostility towards immigrants present in the 19th century.

Text

Emma Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus” as a Petrarchan sonnet, meaning it was a fourteen-line poem written in an iambic pentameter. The first eight lines, or octave, followed a rhyme scheme of ABBA. Within the octave, Lazarus alluded to well-known New York City landmarks to establish the setting of the poem. The “sea-washed, sunset gates” referred to the meeting of the East and Hudson Rivers in New York Harbor, where the Statue rests. The “air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame” referenced, again, the New York Harbor, which separated the cities of Brooklyn and Manhattan and housed the entrance into America for many immigrants.[1] The last six lines, or sestet, had a rhyme scheme of CDCDCD. These lines were spoken by the Statue herself. With “silent lips”, meaning she did not literally talk, she addressed the lands from which the immigrants were fleeing and commanded them to “keep your storied pomp” and instead give her “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses.”[2] The phrase “storied pomp” meant grandeur or extravagance. The “huddled masses” were the large groups of immigrants fleeing their home countries and coming to the United States. The Statue welcomed and guided these immigrants, regardless of how poor a condition they were in, into the waters of the United States by illuminating their path with her “lamp beside the golden door.”[3] The “golden door” that Lazarus described was a literal entrance to the United States, as the New York Harbor was a major immigration reception point. However, it also symbolized the opportunities for an improved life that America presented to immigrants. This concept highlighted the overall theme of the poem, which established the United States as a welcoming land of refuge for persecuted migrants.

Context

Born on July 22, 1849, to a prominent Jewish family in New York City, Emma Lazarus received a private education through various tutors. She studied several languages such as German and French through her private academics. Lazarus published her first book, Poems and Translations: Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen in 1867 at the age of seventeen. She sent a copy of this book to the distinguished poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, and he became her mentor. She dedicated a poem in her second book of poetry, Admetus and Other Poems, to Emerson in 1871. Lazarus published several poems in magazines and published a novel, Alide: An Episode in Goethe’s Life (1874), in the following decade. While her family was rooted in their religious beliefs, Lazarus did not have much of a connection with the Jewish community for most of her life. Lazarus became greatly concerned with the state of immigrants in America in the 1880s, when a series of violent anti-Semetic attacks drove thousands of Jewish Russians to New York.[4]

French political intellectual Édouard de Laboulaye created the idea for the Statue of Liberty in 1865. It was a gift to America celebrating its centennial anniversary of independence and the end of the institution of slavery. Around the time of the poem’s creation, Lazarus was heavily involved in activism for Jewish immigrants and frequently wrote poems promoting Zionism. However, Lazarus was doing this at a time of fierce American nationalism, where “nativists opposed mass immigration for various reasons,” such as the idea that immigrants were “unfit for American democracy” or due to a fear that “the arrival of even more immigrants would result in fewer jobs and lower wages.”[5] These common views led to the creation of anti-immigrant laws, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which set a precedent in the restriction of immigration based on nationality. Laws such as this encouraged hateful sentiment towards foreigners, which was exactly what Lazarus strove to combat in her description of the Statue of Liberty in “The New Colossus.”

Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus” in 1883 for an auction raising money for a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus was originally skeptical of the cause of the auction. In an article, author Michael P Kramer explores Lazarus’s most important reason for writing “The New Colossus,” but observes her initial hesitancy because “the exhibition itself was an ostentatious testament to the acquisitive power of the American moined aristocracy of the Gilded Age…”[6] Kramer’s description of the exhibition highlights that although it seemingly contradicted her ambitions of aiding others, Lazarus put aside her personal reluctance to promote that all Americans should warmly accept immigrants entering the United States. That is why the poem focused on welcoming immigrants to America. The Statue was constructed throughout the year 1885 and was dedicated on October 28, 1886.

Subtext

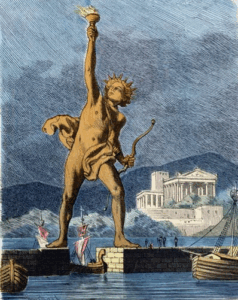

Due to increased nationalistic sentiment, Lazarus set out to write a poem that would offer her “vision of America as a haven for people fleeing ungodly historical circumstances…”[7] The Statue of Liberty was a symbol of American democracy, but to Lazarus, the Statue was a symbol of hope and opportunity for all, especially immigrants. To highlight her view, Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus” to revolve around that position. The poem’s title was a reference to the Colossus of Rhodes, which Edward Hirsch attributes as a monument to “Old World male military power.”[8] Hirsch claims that Lazarus was intent on using the feminine figure of American democracy to oppose the patriarchal Colossus of Rhodes which glorified violence. Max Cavitch further analyzes this concept and claims that “Lazarus’s epithet for the Statue, ‘Mother of Exiles,’ [is] first identified as maternal…”[9] Prior to the construction of the Statue, the most established female personification of the United States was Columbia. However, Columbia was replaced by the maternal Statue of Liberty in 1886 as the main symbol of America.[10] In “The New Colossus”, Lazarus examined the significance of the maternal figure, which she claimed produced a comforting image that welcomed immigrants into the United States. This greatly contrasted with the Colossus of Rhodes, which promoted an idea of brutality in the conquest for power. The Statue of Liberty sparked new ideals of hope and sanctuary, unlike the Colossus of Rhodes which portrayed the “brazen giant” who conquered territory.[11] Additionally, the two statues being compared in the poem were described with contrasting images. Where the imagery of the Colossus honored a sun god, the Statue of Liberty’s imagery revolved the dawning of a new era. Kramer notes that this new era was one where America not only replaced the Old World but improved its flaws and established itself as a haven for immigrants.[12] This new age in America created the possibility of a country that welcomed all peoples onto its shores and set aside any previous prejudices.

Additionally, throughout the entirety of the poem, Lazarus used various images that depicted light. She described a “mighty woman with a torch whose flame is the imprisoned lightning.”[13] A literal interpretation of this sentence would be that Lazarus was describing the right arm of the Statue of Liberty, where her sculpted torch physically lit up with electricity and was a spectacle at the time of its construction. However, the text can also be interpreted as the torch being a guide light in the darkness of oppression for immigrants seeking asylum as it was a “beacon.” The last line of the poem claimed that the Statue was “lifting my lamp beside the golden door.”[14] This was, again, referring to the torch in the Statue’s right hand, but since the phrase was spoken by the Statue herself, she was welcoming immigrants into a land of opportunity.

Conclusion

Although Emma Lazarus left behind a legacy associated with Lady Liberty, she never got to see her words permanently placed on the Statue. Lazarus died on November 19, 1887, but in 1903, “The New Colossus” was placed in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty on a bronze plaque, where it rests today. The Statue of Liberty has remained on Liberty Island in New York Harbor for nearly 140 years where she has greeted millions of immigrants who came to the United States by sea.

For those immigrants, Lazarus’s words reassured them that they would be accepted in the foreign land of the United States, and stressed that they, too, could fulfill the American Dream of a better life with greater opportunities. Lazarus’s poem also helped to spread a new national identity which promised that America was a welcoming country towards immigrants. Today, in an era of intense political polarity over the argument of immigration laws, many Americans, whether they be natural born citizens or migrants, turn to “The New Colossus” as a reminder of the nation that the United States aspires to be; one of sanctuary to those who seek it.

- Emma Lazarus, The New Colossus, 1883, FYS: American History Through Poetry [WEB].

- Lazarus.

- Lazarus.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Emma Lazarus,” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 18, 2025, [WEB].

- James Ambuske et al., “The American Revolution,” Michael Hattem, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018), [American Yawp].

- Michael P. Kramer, “The Raison d’être of ‘The New Colossus,” Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas 22, no. 2 (June 1, 2024): 355–77, 361, [EBSCO].

- Edward Hirsch, The Heart of American Poetry (New York: Library of America, 2022), 72.

- Hirsch, 74.

- Max Cavitch, “Emma Lazarus and the Golem of Liberty,” American Literary History 18, no. 1 (2006): 1–28, 3, [JSTOR].

- Matthew Pinsker, email message to author, October 25, 2025.

- Lazarus.

- Kramer, 366.

- Lazarus.

- Lazarus.

Be the first to reply