US-Latin American relations have been historically complicated, shifting between a quasi-imperialist northern neighbor to isolationism from the region. After the US acquisition of Cuba and the Philippines at the end of the Spanish-American War the United States found itself in a precarious situation. Having historically opposed the idea of imperialism the US now held two territories that did not have a planned path to statehood. From 1989-1902 the US balanced its disdain for imperialism with its desire to control surrounding regions, inevitably resulting in wars in both Cuba and the Philippines.[i] As violence and instability continued throughout Latin America, there began to grow an even stronger anti-imperialist sentiment within Congress and the American public. By 1902 Venezuela had acquired a massive foreign debt that resulted in European intervention within the Western Hemisphere.[ii] The scorn of US imperialist behavior and fear over continued European intervention forced Roosevelt to develop a strategy that would stabilize Latin America without requiring traditional imperialism through military intervention. The strategy which President Theodore Roosevelt would first implement, and President William Taft would continue during his presidency is now known as Dollar Diplomacy.

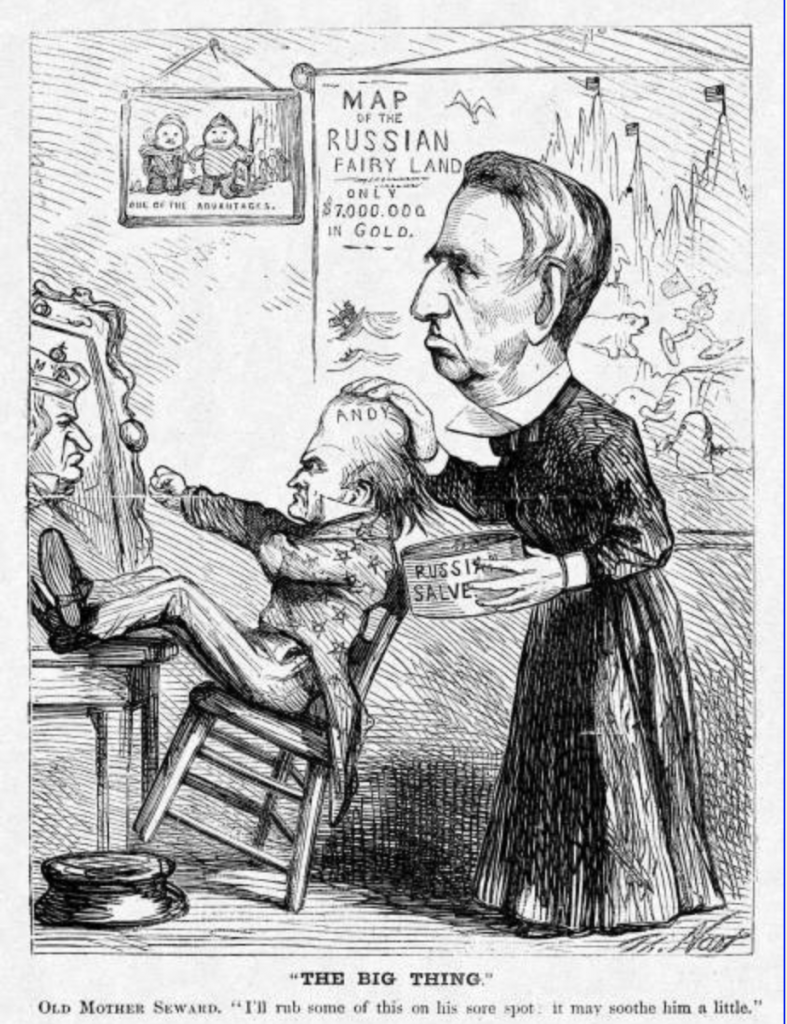

The World’s Constable courtesy of The Library of Congress depecits President Theodore Roosevelt as a constable standing between Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa with a truncheon labeled The New Diplomacy

Eventually, Dollar Diplomacy would come to identify a partnership between private US investment banks and the US government in which customs collections within a Latin American state would be transferred over to a US-appointed company.[iii] Dollar Diplomacy straddled the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and thus explains US policy after its transition from territorial colonialism but prior to the foundation of international financial institutions after WWII.[iv] Spanning the two contrasting eras Dollar Diplomacy may be perceived as the US’ abonnement of imperialism at the forefront of the Progressive age. In reality, it was not the US’ relinquishment of imperialism but solely a shift from territorial to economic imperialism under the guise of humanitarian principles.

Photograph of Theodore Roosevelt courtesy of The Library of Congress

In 1892, during the period of traditional US colonialism in Latin America, prior to the Spanish American War, the San Domingo Improvement Company (SDIC) was founded in the Dominican Republic by New York Democratic, Smith Weed.[v] Due to SDIC’s suspect dealings and continual loan default throughout Latin America, the Dominican Republic acquired an enormous foreign debt and the Roosevelt Administration was forced to act. In 1904, Roosevelt issued a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine which decreed that in the event in which states within the Western Hemisphere participate in negligent finical practices that could result in European intervention it is the US’ responsibility as the “international police power” to intervene.[vi] Under the Roosevelt Corollary, if states in the Western Hemisphere “act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States,” it is only when “it became evident that [states] inability or unwillingness to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American nations” that the US would be obligated to intervene.[vii] Under the corollary, Roosevelt established US dominance as the regional hegemon entitled to intervention as it sees fit.

Photo of Jacob Hollander courtasy of The Library of Congress

Therefore, in 1904 the Dominican Republic became the test subject for a new means of transforming the failing financial system, Dollar Diplomacy. In the following year, under the pretext of the interventionist Roosevelt Corollary, the US intervened in the Dominican Republic’s debt crisis.[viii] With the assertion of the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States had shifted its policy in Latin America to one of commitment and activism. The US believed in their inherent exceptionalism and that under this precedent Roosevelt was doing the “world’s work” in assisting in the development of their Latin American neighbors.[ix] In March of 1905, Roosevelt appointed Jacob Hollander, a prominent John Hopkins economist to operate as an agent for the US to begin investigating the Dominican debt crisis.[x] By December of 1905, Hollander had the Dominican Republic converted to the gold standard and by September of 1906, he had fully adapted the Dominican debt into a persuasive US instrument to establish hegemony in the region.[xi] Hollander had created an outline for Dollar Diplomacy where finance and foreign relations intersected to create a complex system that both US bankers and the government could manipulate for their benefit.[xii] United States policymakers believed that the increase in foreign investment would provide economic and political stability in the region. Within the US in the late nineteenth century, there was a rise in investment banking which provided an avenue to move investments abroad and receive higher foreign interest rates.[xiii] Dollar Diplomacy, therefore, incentivized a partnership to form between investment bankers and the Roosevelt administration with a two-sided mission, for investment bankers to get rich off Latin America and for the US to have influence in the region without taking on its political sovereignty. Roosevelt saw Dollar Diplomacy as a gift to Latin America, specifically, the Dominican Republic so that “stability and order and all the benefits of peace are at last coming to Santo Domingo, [the] danger of foreign intervention has been suspended” all due to the US’ intervention.[xiv]

It wasn’t until after the Roosevelt Administration, during William Taft’s presidency that Dollar Diplomacy transitioned from informal arrangements to official US policy, ultimately becoming a key aspect of Taft’s foreign policy.[xv] President Taft and Secretary of State Philander Knox initially attempted to institute Dollar Diplomacy through treaties, but after receiving pushback from Latin American countries and Congress they converted to a system of “colonialism by contract” that more resembled what Roosevelt had implemented in the Dominican Republic.[xvi] In President William Howard Taft’s fourth State of the Union Address, he described the shift from traditional imperialism to Dollar Diplomacy as a “response to modern ideas of commercial intercourse” which is characterized as “substituting dollars for bullets” in order to avoid direct military intervention.[xvii] Overall during the Taft administration George Herring concluded that Dollar Diplomacy amounted to nothing more than increased instability and US military intervention in Latin America, the exact of which the US claimed to be trying to prevent.[xviii] Even though Taft claimed to be acting in the interest of “idealistic humanitarian sentiments” he and Knox still maintained an air of ethnocentrism in which they believed in US dominance over the “rotten little countries” of Latin America.[xix]

The Crown Prince courtesy of The Library of Congress depicts President Theodore Roosevelt, wearing royal robes, holding on his shoulders and presenting a diminutive William H. Taft wearing a crown

Through Dollar Diplomacy both the Roosevelt and Taft Administrations were able to use commercial-government partnerships throughout Latin America and beyond to facilitate fiscal reform without the US taking on complete responsibility for the sovereignty of states. Under the definition of imperialism in which a state assumes a part of the sovereignty of another in order to foster a dependent relationship, the US’ dominance over the financial systems of Latin American countries through Dollar Diplomacy represents a form of imperialism even though the US never formally held the territories.[xx] No matter what intentions the US claimed to have during this period there was an underlying exploitive nature in their actions, since the primary objective of the policies were political, the stability of Latin America, not the development of states for pure humanitarian gains.[xxi] Dollar Diplomacy was the manifestation of US quasi-imperialist ideals where the US sought to achieve its best interest with little regard for other states.[xxii]

[i]Ellen D. Tillman, “Military Diplomats and Dollar Diplomacy” In Dollar Diplomacy by Force: Nation-Building and Resistance in the Dominican Republic,” 28-52. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 22. [JSTOR]

[ii]George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: US Foreign Relations since 1776(New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 370.

[iii]Cyrus Veeser, “Inventing Dollar Diplomacy: The Gilded-Age Origins of the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,” Diplomatic History, Vol. 27, No. 3 (2003): 325. [JSTOR]

[iv]Emily S. Rosenberg and Norman L. Rosenberg, “From Colonialism to Professionalism: The Public-Private Dynamic in United States Foreign Financial Advising, 1898-1929,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 74, No. 1 (1987): 59. [JSTOR]

[v]Eric Paul Roorda, “Imperial Improvement,” Diplomatic History, Volume 28, Issue 5, (2004): 796. [JSTOR]

[vi]Rosenberg, 63

[vii]President Theodore Roosevelt, “Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union.” (speech, Washington, DC, December 6, 1904) The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fourth-annual-message-15

[viii]Roorda, 795

[ix]Herring, 364.

[x]Cyrus Veeser, “Concession as a Modernizing Strategy in the Dominican Republic,” The Business History Review, Vol. 83, No. 4 (2009): 753. [JSTOR]

[xi]Emily S. Rosenberg, “Foundations of United States International Financial Power: Gold Standard Diplomacy, 1900-1905,” The Business History Review, Vol. 59, No. 2 (1985): 192. [JSTOR]

[xii]Veeser, 323.

[xiii]Rosenberg, 62

[xiv]President Theodore Roosevelt, “Fifth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union.” (speech, Washington, DC, December 5, 1905) The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fifth-annual-message-4

[xv]Herring, 372

[xvi]Herring, 373

[xvii]President William Howard Taft, “Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union.”(speech, Washington, DC, December 3, 1912) The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fourth-annual-message-16

[xviii]Herring, 373

[xix]President William Howard Taft, “Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union.”(speech, Washington, DC, December 3, 1912) The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fourth-annual-message-16; Quoted in Herring, 373.

[xx]Rosenberg, 65

[xxi]Herring, 364

[xxii]Dana G. Munro, “Dollar Diplomacy in Nicaragua, 1909-1913,” The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 38, No. 2 (1958): 209. [JSTOR]