Introduction

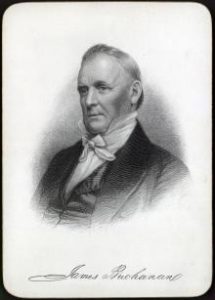

On December 19th, 1859, President James Buchanan delivered his third State of the Union, where he declared, “All lawful means at my command have been employed, and shall continue to be employed, to execute the laws against the African slave trade. After a most careful and rigorous examination of our coasts, and a thorough investigation of the subject, we have not been able to discover that any slaves have been imported into the United States except the cargo by the Wanderer.” [1] Buchanan’s State of the Union indicated to international and domestic forces that the Buchanan administration had taken significant strides to combat the illegal slave trade. Beginning in 1858, Buchanan accomplished more to suppress the illegal slave trade than any American president. [2] President Buchanan expanded American naval action to patrol the waters of Cuba, the African coast, and the United States; increased funding for the enforcement of the slave trade; and concentrated the duties of the slave trade under the Department of the Interior. [3]

Buchanan’s words, however, proved untrue: a year after the Wanderer ship landed, the schooner Clotilde smuggled 116 Africans into Mobile Bay in the autumn of 1859. [4]

Although dramatized, Buchanan’s 1858 State of the Union Address demonstrates the ways in which Buchanan used his administration’s successful campaign against the slave trade as an international and domestic posture. Following the successful campaign against the slave trade, President Buchanan used the abolition of the slave trade to advocate for the annexation of Cuba. Moreover, Buchanan’s attempts to abolish the slave trade indicated the president’s moderate stance to an increasingly fractured American public. Pragmatic and advantageous, President Buchanan gained political leverage by launching a successful campaign against the slave trade and used it to advocate for his own domestic and expansionist political interests.

A Brief History of the United States and the International Slave Trade

Legally abolished in 1808 under the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807, the American slave trade continued illegally throughout the early 19th century. The 1807 Act provided no means to effectively enforce the law and despite revisions to the law in 1818, 1819 and 1820, American citizens continued to engage in the trafficking of persons. Despite frequent reports of American violation of slave trade laws, the American government “turned a blind eye to the involvement of American citizens in the trade.” [5]

American participation in the illegal slave trade greatly frustrated the British government, which emerged as the leader in the slave trade abolition in the late-18th century. Throughout the early 19th century, Great Britain repeatedly pressured the United States to grant British officials the right to search American vessels suspected of carrying slaves. [6] Unlike other European countries, the United States refused the British right of search. The legacy of British impressment and conscription, which onset the War of 1812, remained active in the American imagination, resulting in a general unwillingness to concede any amount of sovereignty to grant the British the right of search. [7]

By 1839, the United States became one of the few countries opposing the British right of search, escalating American involvement illegal slave trade; the United States flag became the “only viable cover for the slave trade to continue.” [8] As described by a New York slaver interviewed for Debow’s Review in 1855, “We run up the American flag and if they come on board, all we have to do is show our American papers, and they have no right to search us. So, they growl and grumble and go off again,” when asked if they were fearful of British fleets paroling water.” [9] Increased American violation of slave trade laws throughout the 1850s prompted the British to add pressure on the United States, escalating tensions between the two nations throughout the 1850s. [10]

James Buchanan and the Slave Trade

James Buchanan became the 15th president of the United States during a period of increased British activity against the international slave trade. In what American historian, Don Fehrenbacher, describes as the “Forgotten crisis of 1858,” tensions between the United States and Great Britain throughout spring 1858 when British warships increasingly searched and seized American trading vessels to search for illegal slave trading activity. [11] In May 1858, President James Buchanan received news of increased British search of American trading vessels from Secretary of State Lewis Cass, who reported of “the forcible detention and search of American vessels by British armed ships-of-war in the Gulf of Mexico, and in the adjacent seas.” [12] Amounting British pressure off the Cuba coast forced president Buchanan to act quickly, retaliating against British pressure by expanding American action against the slave trade; Buchanan’s swift action quelled British pressure and offset potential conflict.

In response to British search of American ships in Cuba, Buchanan and sent a fleet of four American warships to patrol the coast of Cuba, which remained there until the British eventually retreated in June of 1858. [13] Although Buchanan maintained the “established policy of apathy” before the crisis in Cuba, following the forgotten crises, Buchanan’s policy towards slave trade suppression became the most successful in American history. [14]

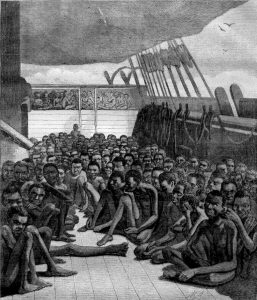

Sketch of the Wildfire, a slave ship captured by the American squadron off the coast of Cuba in 1860, courtesy of PBS.

Following the initial conflict in Cuba, President Buchanan successfully enacted a series of measures to limit the illegal slave trade. In 1858, Buchanan consolidated the enforcement of the slave trade to the Department of the Interior. In March 1859, Congress appropriated $75,000 to assist the suppression of the slave trade, $45,000 of which went to the meager American fleet patrolling for slave trade ships off the coast of Africa. [15] That same year, four ships were added African squadron [16] Before 1858, the African fleet generally consisted of “four vessels, three of which were usually second or third-class sloops.” [17] In July of 1859, African squadron’s base moved closer to slave trading activity, from Porto Praia to Sao Paulo de Loando. [18] Moreover, President Buchanan allocated four American steamers to patrol the waters off the coast of Cuba for slavers in 1859; before then, no American ships ordered to patrol for slave trading were allocated to Cuba [Davis 452] In November of 1859, President Buchanan allocated an additional ship to patrol the waters of the South, from the coast of Georgia to Florida coast. [19]

President Buchanan’s efforts to suppress the slave trade proved incredibly successful. Throughout the 1840s and early 1850s, few slavers were arrested. Officials failed to arrest a single slave ship in 1843, 1843, 1848, and 1849; officials arrested three slavers in 1850; ten slave vessels in 1852, 1853, 1854, and 1856; and no documentation of arrests exists for 1851 and 1855. [20] During Buchanan’s administration, 42 arrests were made between 1857 and 1860 [21] According to Ted Maris-Wolf, 75 percent of all Africans rescued from the slave trade in the 19th century occurred in 1860 alone. [22]

Why Did Buchanan Do This?

Buchanan’s unprecedented action against the slave trade demonstrates the 15th presidency’s pragmatic and ambitious approach to foreign policy. Confronted with British search and seizure of American ships in Cuba, Buchanan responded quickly, expanding American action to combat the slave trade. Once tensions deescalated, however, Buchanan utilized his successful campaign against the slave trade as leverage to pursue his own political interests. While Buchanan’s immediate retaliation against the British during the 1858 crisis in Cuba served to “vindicate American motives in the face of British criticism,” the “standoff with Britain proved especially useful to Buchanan, and he made the most of it.” [23]

Domestically, Buchanan’s action against the British search of American ships helped Buchanan appear moderate, countering “proslavery extremists and abolitionist critics at home by demonstrating America’s willingness to live up to its obligations as a moral world power.” [24] Scholar Don Fehrenbacher asserts this notion, saying that Buchanan sought to “distance himself from proslavery extremism in domestic politics” when retaliating against British search [25]. Public opinion regarded the Buchanan administration action against the British in the spring of 1858 highly. Moreover, Congress approved Buchanan’s actions in 1858 in an “uncharacteristic bipartisan unity.” [26] On June 29, 1859, the New York Times applauded Buchanan’s action in the Caribbean, saying “we regard this as a substantial and most important triumph of American diplomacy and American interests. It is a result of which the Administration of Mr. Buchanan may well be proud…for its action in this matter, it deserves and will receive the cordial approval of the American people.” [27]

The volatility of partisan politics, which threatened the unraveling of the Union greatly weighted on Buchanan’s presidency; combating the slave trade helped diffuse such divides. Scholar Ralph Davis even suggests Buchanan’s actions were in part, done to better the chances of the Democratic party in the nearing presidential election. [28] Throughout Buchanan’s presidency, Republicans attacked the president and Democrats for their inability to combat the slave trade. [27] Buchanan could potentially offset Republican attacks about the ineffectiveness of the Democrats by aggressively combating the slave trade.

Internationally, Buchanan’s posturing as a moral world power allowed him to advance his expansionist goals in Cuba. Well before his presidency, Buchanan attempted advocated for the annexation of Cuba. [28] Although it is clear that Buchanan first combated the slave trade in response to British pressure, Buchanan later used American action against the slave trade to argue for the annexation of Cuba. Scholar Ted Maris-Wolf argues that Buchanan gained the “moral justification… to make yet another monumental nineteenth-century land acquisition.” [29] It is clear Buchanan pursued Cuban annexation after his successful campaign against the slave trade. In President Buchanan’s 1858 State of the Union address, the president cited the United States’ moral obligation to end the slave trade, advocating for the annexation of Cuba: the last place on earth openly supportive of the slave trade. Buchanan’s message to Congress stated,

The truth is that Cuba… is the only spot in the civilized world where the African slave trade is tolerated… The late serious difficulties between the United States and Great Britain respecting the right of search, now so happily terminated, could never have arisen if Cuba had not afforded a market for slaves… It has been made known to the world by my predecessors that the United States have on several occasions endeavored to acquire Cuba from Spain by honorable negotiation. If this were accomplished, the last relic of the African slave trade would instantly disappear. [30]

Buchanan’s 1858 State of the Union address linked the abolition of the international slave trade with the acquisition of Cuba, implying that the slave trade could not end without the American annexation of Cuba [31] Buchanan’s expansionist interests when advocating for the annexation of Cuba, however, were not obscure; many newspapers addressed Bachchan’s expansionist interests. In January of 1859, the Douglass’ Monthly retorted, “He speaks of the island as an annoyance. It must be a very welcome and pleasing annoyance, indeed.” The article continued, “[President Buchanan’s] motto is, long live the domestic slave-trade, but the foreign must come to an end. His moral obfuscation is unpardonable.” [32] Commented on by Douglass’ Monthly, Buchanan’s rhetoric against the slave trade actively advocated for the annexation of Cuba, demonstrating Buchanan’s advantageous approach to diplomacy; confronted with the threat of British search and seizure in the spring of 1858, President Buchanan acted swiftly, deescalating tensions and using the international dynamics to benefit his political agenda.

Although James Buchanan never achieved his desires to acquire Cuba, the 15th president of the United States launched an incredibly successful campaign against the slave trade. Moreover, Buchanan’s actions following the international endeavor demonstrated the ways in which Buchanan effectively created favorable circumstances for himself in times of crises. Pragmatic in his approach to diplomacy, Buchanan responded to British pressures in the Caribbean in 1858 and remedied American tensions with the British regarding the slave trade. Buchanan however, took advantage of what began as an effort to ease British pressures, using his administration’s suppression of the slave trade to quell sectional difference and advance his expansionist interests in Cuba. [33]

[1] John Bassett Moore, edited, The Works of James Buchanan, Vol. 10 (Philadelphia: Washington Square Press, 1910), 342-343. [ONLINE]

[2] Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 187. [EBOOK]

[3]Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 446-459. [JSTOR]

[4] John M. Belohlavek, “In Defense of Doughface Diplomacy,” Florida Scholarship Online, (2013): 118. [ONLINE]

[5] Randy J. Sparks, “Blind Justice: The United States’s Failure to Curb the Illegal Slave Trade,” Law and History Review 35, no.1 (2017): 61 and 79.

[6] Matthew Mason, “Keeping up Appearances: The International Politics of Slave Trade Abolition in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World,” The William and Mary Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2009): 811 [JSTOR]; Randy J. Sparks, “Blind Justice: The United States’s Failure to Curb the Illegal Slave Trade,” Law and History Review 35, no.1 (2017): 61.

[7] Matthew Mason, “Keeping up Appearances: The International Politics of Slave Trade Abolition in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World,” The William and Mary Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2009): 822.

[8]Randy J. Sparks, “Blind Justice: The United States’s Failure to Curb the Illegal Slave Trade,” Law and History Review 35, no.1 (2017): 61-62.

[9] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 448.

[10] Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002): 185.

[11] Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002): 185.;Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 58. [JSTOR]

[12] Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 59. Maris-Wolf 58-59

[13] Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 58-59. [PROJECTMUSE]

[14] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 441.

[15]Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 451.

[16] Karen Fisher Younger, “Liberia and the Last Slave Ships,” Civil War History 54, no. 4 (2008): 432. [PROJECT MUSE]

[17] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 452.

[18] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 453.

[19] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 453.

[20] Karen Fisher Younger, “Liberia and the Last Slave Ships,” Civil War History 54, no. 4 (2008): 431. ; Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 454.

[21] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 445. ; Karen Fisher Younger, “Liberia and the Last Slave Ships,” Civil War History 54, no. 4 (2008): 433.

[22] Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 61.

[23] Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002): 187; Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 58.

[24] Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 58.

[25] Karen Fisher Younger, “Liberia and the Last Slave Ships,” Civil War History 54, no. 4 (2008): 431.

[26] Karen Fisher Younger, “Liberia and the Last Slave Ships,” Civil War History 54, no. 4 (2008): 431.

[27] “The Right of Search and the Slave Trade,” The New York Times, June 29, 1858, ProQuest Historical Newspapers. [Online archive]

[28]Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 458-459

[29] Robert Ralph Davis Jr., James Buchanan and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1858-1861,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 33, no.4 (1966): 458-459

[30] “James Buchanan,” Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Buchanan-president-of-United-States#ref673275

[31] Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 60-61

[32] John Bassett Moore, edited, The Works of James Buchanan, Vol. 10 (Philadelphia: Washington Square Press, 1910), 251.

[33]Ted Maris-Wolf, “Of Blood and Treasure”: Recaptive Africans and the Politics of Slave Trade Suppression,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no. 1 (2014): 58.

[34]“The President’s Message” Douglass’ Monthly, January 1859, Accessible Archives.

[35] Karen Fisher Younger, “Liberia and the Last Slave Ships,” Civil War History 54, no. 4 (2008): 432