Over the course of the last seven months, I have had the incredible opportunity to study abroad in Bologna, Italy. While this particular Dickinson program is not particularly adverse (due to the absence of a language requirement and virtually all courses being taught in English), the breadth of foreign scholars that have taught our lessons has been immense. In terms of the history courses I have enrolled in specifically, there are two professors that stand out as interesting examples of just why studying abroad can teach a student a thing or two about “how the other half lives.”

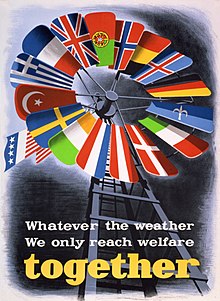

In the Fall, Professor Mark Gilbert, an Englishman employed by Johns Hopkins’ SAIS program, taught a course on the development of the European Union. Currently, Professor Mario Del Pero, an Italian teaching at numerous institutions, brought a course to Dickinson titled Transatlantic Relations. While the courses are very similar in content, these two scholars have nearly diametrically opposed viewpoints on the relevance of certain individuals and events. In fact, I usually end up feeling a bit silly when my contributions to Prof. Del Pero’s course include information learned from Prof. Gilbert that is almost immediately dismissed. For example, Prof. Gilbert is what some might label an “integrationist.” In essence, he is a general fan of the EU. Therefore, the minor organizations and treaties that built up to the formation of the EU play a principal role in his lectures, in addition to America’s altruistic contributions. Prof. Del Pero is quite the opposite. He does not see the US as altruistic at all, and is more concerned with the development of the Cold War as a means to integration that probably should not have occurred as it did. I happened to suggest in class that the Marshall Plan was crucial to Europe’s economic recovery following the Second World War and that it was based on American generosity. Needless to say, Prof. Del Pero enjoyed poking fun at me for the rest of the lesson.

I have personally never noticed such a distinct professional difference among Dickinson’s faculty in Carlisle. While we study historiography in History 304 and beyond, seldom does a history major get to experience it first-hand, in the classroom. These two excellent and engaging scholars struggle to find common ground, yet they encourage meaningful thought about what they are teaching (at least for this history major).

Classroom experiences like this are probably the most valuable part of studying abroad. For all of you future-study-abroaders out there, don’t be afraid to step outside Dickinson’s limestone walls and into the red brick of Emilia-Romagna. You just might accidentally learn something.