The Litigants

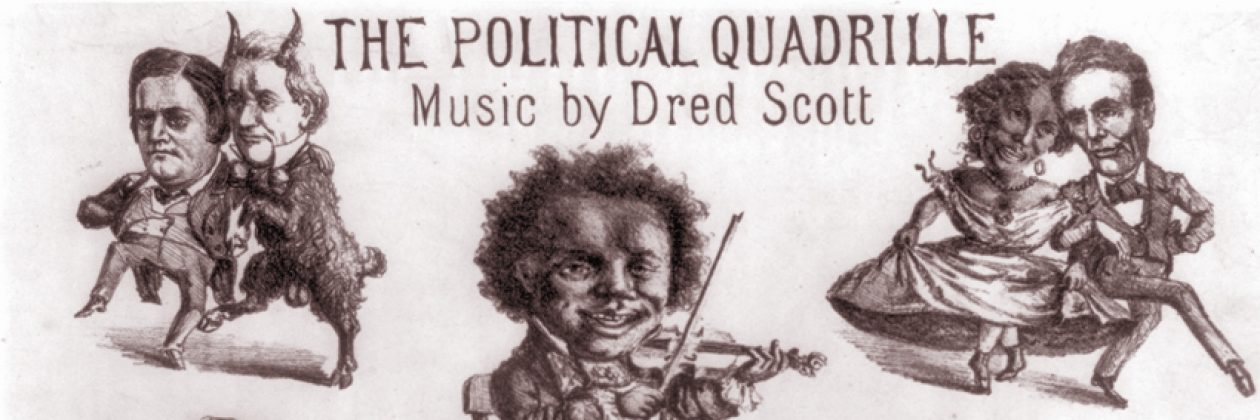

Dred Scott, a Virginian born slave to plantation owner Peter Blow, moved to St. Louis where Scott and his family were sold to Dr. John Emerson. Scott was temporarily taken to Illinois, a free state, then to Wisconsin, a free territory where he married Harriet Robinson. With the death of Dr. Emerson, the Scotts were handed to his wife, Irene. In 1846, Scott sued Irene Emerson in the Missouri state court for his and his wife’s Harriet freedom, as well as their two daughters, Lizzie and Eliza. Eleven years later, the case was brought before the Supreme Court and Scott and his family remained as slaves. Irene’s second husband, Dr. Chaffee embarrassed to own slaves, sold the Scotts back to the Blow family who emancipated the entire family. Scott became a porter at Barnum’s Hotel in St. Louis but died a year later from tuberculosis.

Harriet Robinson Scott, a Virginian slave was taken to Ft. Snelling, Wisconsin where she met and married Dred Scott. In 1846, Dred and Harriet sued Irene Emerson for freedom; however, only Dred’s case advanced as Harriet’s would depend on her husbands ruling. The Scotts had experienced several trials and fought for eleven years that resulted in the Supreme Court’s decision to deny them citizenship. On May 26, 1857 the Scotts were freed by the son of Dred’s first owner, Taylor Blow. Harriet lived for eighteen more years, worked in a laundry room and witnessed the end of slavery.

Dr. John Emerson, a United States Army surgeon, purchased Dred Scott after his previous owner Peter Blow could no longer afford him. Dr. Emerson traveled with Scott to Illinois, where slavery was illegal, in 1833 and then to Ft. Snelling, Wisconsin where slavery was not permitted under the Missouri Compromise. There, Dr. Emerson purchased Harriet Robinson who, with permission, later married Dred. Emerson left his wife, Eliza Irene Sanford Emerson, in charge of Dred and Harriet Scott to join to the Seminole War in Florida in 1840. Emerson came back to St. Louis a year later but he passed away in 1843.

Irene Emerson Sanford, married initially to Dr. John Emerson, inherited Dred and Harriet Scott as well as their two children, Eliza and Lizzie in 1843. Dred and Harriet Scott sued Irene for freedom. The case was tried twice with Scott as the winner after the second trial. Irene appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court and the court voted two to one to reverse the case. Irene left St. Louis to marry Dr. Calvin Clifford Chaffe. She left the case to her brother John F.A. Sanford who became the controller of Dr. Emerson’s property. After the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sanford decision, Irene’s husband, an abolitionist, sold the Scotts back to their previous owner Taylor Blow.

John F. A. Sanford, a New York resident, business man and brother of Irene Emerson was handed responsibility of the Dred Scott case when Irene left to marry Dr. Chaffee. Sanford had previously become the executor of the Emerson estate. Dred Scott sued Sanford in 1854, but since Emerson was from New York the case went before the federal courts. Sanford’s attorney argued Dred Scott was not a citizen and could not sue in federal court and the case was then brought to the Supreme Court. In the 1857, Dred Scott v. Sanford decision, the Scotts remained as slaves.

The Lawyers

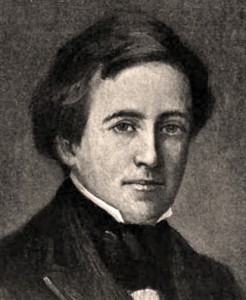

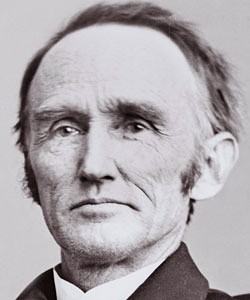

Montgomery Blair, a Kentucky native and Missouri resident, became Dred Scott’s lawyer in 1856. While Blair lost the case to Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, he argued that Scott earned his freedom when he was taken to free territories. Blair further stated under the Missouri Compromise of 1820, slavery was banned in those territories and Congress held the right to prohibit slavery. Afterwards he sought to defend the Union’s principles and became post-master general during the Civil War. Blair remained in Maryland politics until he passed away in 1883.

George Ticknor Curtis, a Massachusetts lawyer and brother to U.S Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Curtis, represented Dred Scott in 1856-1857. As a staunch believer that the Constitution contained a limited amount of power on the national government, Curtis argued the Missouri Compromise to be constitutional. The Court dismissed Curtis’s arguments that Congress held the power to control slavery within the territories. Curtis remained committed to his belief that the Constitution granted too much power to the national government and became a prominent patent lawyer. He also wrote a book regarding the role of the Constitution during the Civil War until he died in 1894.

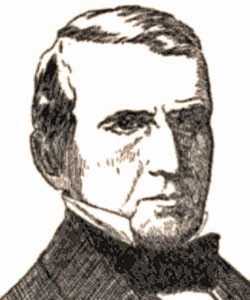

Henry S. Geyer, was born in Maryland but later moved to Missouri to practice law. As a proslavery lawyer and Senator, Geyer and Reverdy Johnson defended John F. A. Sanford in the Dred Scott v. Sanford case stating claims that were reinforced by Chief Justice Taney. Geyer argued Scott’s race prevented him from being able to become a citizen and his temporary visit to Illinois and Wisconsin did not constitute him as free because the Missouri Compromise was invalid. Geyer retired from the Senate in 1857 after one term and passed away two years later.

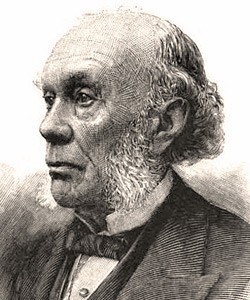

Reverdy Johnson, a lawyer from Maryland, worked to prevent the federal government from interfering with the slave institution. Johnson argued on behalf of Sanford that Congress did not have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories. Johnson and Geyer questioned whether or not Scott’s temporary appearance in the free territories granted Scott and Harriet freedom. Johnson spent the rest of his years as a U.S Senator of Maryland and lawyer. He remained active to preserve the Union and promote principles in the Constitution until he died from a crushed skull in 1876.