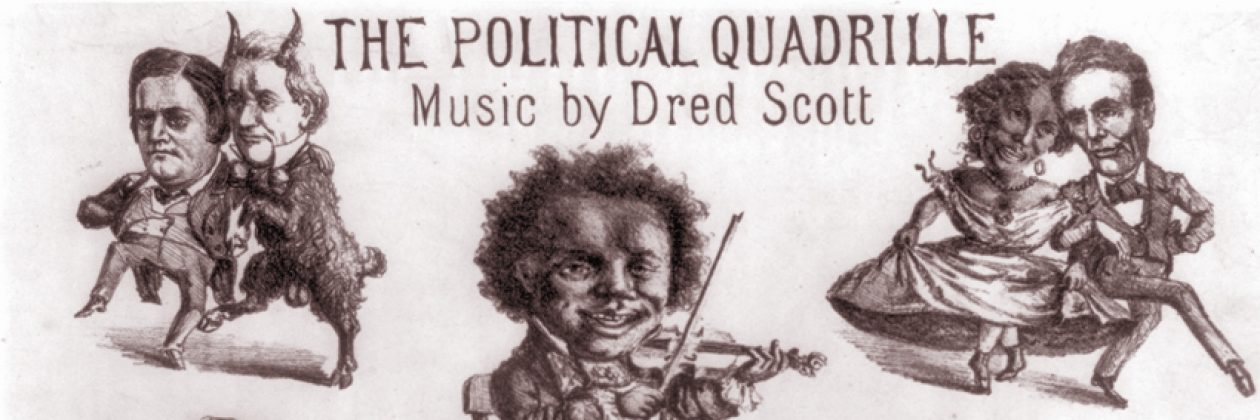

When Chief Justice Taney swore in President-elect James Buchanan on March 4, 1857, he whispered into Buchanan’s ear. Two days later, the Chief Justice read his decision of the Dred Scott case that reshaped the course of American history. Rumors floated that Taney and Buchanan had intervened in the Court’s decision along with their third college tie, Justice Grier. Regardless of what was actually whispered, Taney ruled that blacks, slaves or free, were not nor could not become citizens of the United States. His opinion was not the direct cause of the Civil War; however, it further shattered the Union as well as Taney’s personal reputation.

Roger Brooke Taney was born on March 17, 1777 on the Taney Plantation in Calvert County, Maryland. As a privileged child, he was privately educated and entered Dickinson College in 1792 to prepare for a profession in politics. He practiced reading the law and was admitted to the Maryland bar in 1799. He served as a Federalist representative and then to moved Frederick because it was “with a view to profit, the best point of practice in the State” [1]. Taney married Anne Key in 1806 and had six daughters and a son who died as an infant. Taney mirrored his mother’s nature in the treatment of his children and family slaves. He joined a group of young Marylanders who attempted to protect free blacks from being kidnapped. A decade later, Taney was elected to the Maryland State Senate. In 1820, he was recognized as a leading attorney in Maryland and assumed the position of State Attorney General seven years later.

The Federalist Party splintered into the Democratic and Whig Party over the power of the federal government. At this time, Taney and a majority of others joined the Democrats and took over the nationalist programs of the Federalists [2]. He became a supporter of Democrat Andrew Jackson in 1824 when letters were published in which Jackson attacked the unfaithful wing of the Federalist Party, a group that listed Taney’s enemies [3]. Thus, Taney served as Jackson’s chairman to the Central Committee of Maryland in 1828 and continued his role as Attorney General while also assuming the position of Secretary of War.

In 1833, President Jackson nominated Taney as Secretary of the Treasury until his Senate confirmation was rejected and he left a year later. When Taney’s nomination for a seat on the Supreme Court was barred Jackson intervened and nominated him Chief Justice on December 28, 1835 [4]. Marked as one of the most prominent Chief Justices, Taney’s time on the bench is recognized through cases that favored states rights, decentralization and the inevitable struggle to preserve the Union. The first twenty years on the Taney Court, as seen by historian Carl B. Swisher, had proven to be “a court of law” and chose not to “create a confused image of itself to dilute its judicial performance by giving official advice either to the President or to Congress” [5]. However, from 1836 to the Dred Scott case in 1857, a justification for slavery was established in America. Taney’s controversial opinions in Dred Scott and cases during the Civil War plagued his reputation.

As Taney grew older and weaker, on August 6, 1863, he wrote to a dear friend that he did not believe the next Court would, “ever be again restored to the authority and rank which the Constitution intended to confer upon it” [6]. Roger B. Taney died on October 12, 1864, with many Northern supporters mourning the destructive aftermath of the Dred Scott case.

Personal Characteristics

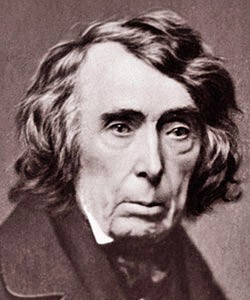

Roger Taney, chronically ill for most of his life, was tall, gaunt, and flat-chested, with broad shoulders and he walked with “inverting and hesitating steps [7]. Taney’s appearance was ” irregular, his teeth discolored with tobacco, his gums visible when he smiled… and his black clothes were ill-fitted [8]. His long hair “cascaded over his collar” and swept across his forehead. [9] Taney’s natural face “was so dour that even his severest critics professed to see a sinister look in it.” [10]

When he spoke, he commanded the respect and attention of the judges, despite his low and hollow voice. He developed his father’s temper but was also heavily influenced by his mother’s sincerity referring to her as “pious, gentle and affectionate” [11]. When Taney’s wife and youngest daughter died of yellow fever in 1855 he told a friend he would keep his political position but “shall enter upon the duties with the painful consciousness… with a broken health and broken spirit” [12].

When Taney joined President Jackson’s cabinet in 1828 he not only switched his political party from Federalist to Democrat, but also his position on slavery. Before Jackson’s influence, Taney manumitted his family slaves and believed they should be free at some point [13]. In 1819 Taney supported gradual emancipation and believed Congress should restrict the amount of slavery spreading [14]. However, with the great debate in the 1850’s over slaveholder rights, Taney opposed emancipation and felt compelled to represent the interests of the South, namely the slavery institution. Taney also developed a distaste toward northern abolitionists’ because he worried they would threaten the interests of the South and the Union.

Key Moments

Taney took a risk in 1819 defending Jacob Gruber, a white Methodist minister who preached slavery as a “national sin” and a disgrace “to hold articles of liberty and independence in one hand and a bloody whip in the other” [15]. Gruber was charged with conspiring to raise a rebellion in the state. Taney claimed Gruber’s sermon was protected by freedom of speech and despite claims of Gruber inciting slaves to come, the only way they could have was by the permission of their master. Taney agreed with Gruber’s denouncement of slavery, calling slave masters “reptiles” and the slave institution as “a blot on our national character” [16]. Taney won his case and used it to attack the entire institution rather than just the boundaries of the case.

In 1785, the Massachusetts legislature asked the Charles River Bridge Company to construct a bridge and collect tolls. In 1828, the state asked the Warren Bridge Company to build a free bridge. In Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, the Charles River Bridge Company sued the legislature, claiming they would lose business to the Warren Bridge. Taney ruled that the state did not establish a contract that prevented a bridge from being built in later years and in the interests of the community, having another bridge held priority [17]. This case was the mark of the Taney court shifting the interests of nationalism to states rights.

In 1851, the Supreme Court denied the motion to review a decision of the Kentucky court appeals that a brief visit to Ohio did not constitute Kentucky slaves free. Chief Justice Taney ruled in Strader v. Graham that the laws of Kentucky, not Ohio, confirmed their status the moment they voluntarily went back to Kentucky. [18] Taney’s opinion had been consistent with rulings favoring state rights.

At eleven o’clock on March 6, 1857, reporters and observers gathered to hear Chief Justice Taney determine the fate of the eleven-year old Dred Scott decision [19]. Taney ruled that since blacks were not seen as citizens when the Constitution was ratified they were never intended to be citizens. Taney further declared, even though Dred Scott had been taken to Missouri as a slave, he was not free for temporarily visiting a free territory in the Missouri Compromise [20] and therefore could not sue in federal court. Finally, Taney concluded that Congress did not have the power to limit slavery in the territories, which put the Court on the side of slaveholders [21]. The New York Tribune stated, “Chief Justice Taney’s… arguments were based on gross historical falsehoods and bald assumption, and went the whole length of the extreme southern doctrine” [22]. The Dred Scott decision had back-fired on those who had wished it would settle the issue that threatened the preservation of the Union.

The Abelman v. Booth case, regarding an abolitionist’s avoidance of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law was brought before the Taney court in 1859. Taney, speaking unanimously for the court, had taken the side of a nationalist – declaring that a state must follow “the same judicial authority in relation to any other law in the United States” [23]. Taney had hoped copies of his decision would be in demand, but Historian James F. Simon stated the wide disinterest in his opinion was a result in the “drop of the Supreme Courts prestige.” [24]

Taney’s difficulties throughout the latter part of his 28-year term mirrored the changing political perception of the Court, coupled with his desire to protect the rights of slaveholders. He administered the oath to Abraham Lincoln in 1861 whom he utterly detested and spent his last years cynical and eager to denounce to the President’s Civil War policies. In Ex Parte Merryman,Taney criticized Lincoln for the house arrest of John Merryman, a confederate sympathizer. Taney argued President Lincoln did not alert the courts nor the public that he suspended the writ of habeas corpus and exercised “a power which he does possess under the constitution.” [25]

Further Readings

For an autobiographical account of Taney’s life, read Samuel Tyler’s, Memoir of Roger B. Taney (1872). For more information on Taney’s opinion in the Dred Scott case, refer to Benjamin Chew Howard’s Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges thereof, in Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sanford (1857) and the Merryman case in Taney’s words can be read in Taney’s pamphlet “Roger Brooke Taney issues an opinion on whether the President of the United States may suspend the Writ of Habeas Corpus (1861).” For a wide perspective of the Taney’s time as Chief Justice there is Carl B. Swisher’s The Taney Period (1974) as well as Swisher’s Roger B. Taney (1935). To better understand Taney’s relationship with Lincoln read, James F. Simon’s Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney, Slavery, Secession and the President’s War Powers (2006).

Works Cited

[1] Samuel Tyler, Memoir of Roger B. Taney, (Baltimore: John Murphy & Co, 1872), p. 95

[2] Carl B. Swisher, Roger B. Taney, (New York: Macmillan Company, 1935), p 121

[3] Ibid., p 122

[4] John Osborne and James W. Gerencser, eds., “Roger Brooke Taney,” Dickinson Chronicles, http://chronicles.dickinson.edu/encyclo/t/ed_taneyR.htm.

[5] Carl B. Swisher, The Taney Period, (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1974), p. 2

[6] Tyler, p. 354

[7] Jack Beaty, Age of Betrayl: The Triump of Money in America 1865-1900, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007) p. 111

[8] Carl B. Swisher, The Taney Period, p. 17

[9] Brian McGinty, Lincoln and The Court, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008)p. 14

[10] Ibid., p.14

[11] James F. Simon, Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney, Slavery, Secession and the President’s War Powers, (Simon & Schuster, 2006), p. 6

[12] Tyler, 328

[13] Carl B. Swisher, Roger B. Taney, p.93

[14] Timothy S. Huebner, “Roger B. Taney and the Slavery Issue: Looking beyond – and before – Dred Scott,” Journal of American History, (2010): 17-38

[15] Huebner, p. 23

[16] Huebner, p. 34

[17] Alex McBride, “Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837).” PBS. January 1, 2007. Accessed February 27, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/print/landmark_charles.html.

[18] Kenneth M. Stamp, America in 1857, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 84

[19] Ibid., 93

[20] The Missouri Compromise decided in 1820 prohibited admitted Missouri as a Slave state and Maine a free state. It also stated, with the exception to Missouri, slavery was prohibited in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36 30′ latitude.

[21] Swisher, Roger B. Taney, p. 506

[22] Swisher, The Taney Period , p.633

[23] Simon, p. 161

[24] Ibid., 163

[25] Arthur T. Downey, “The Conflict between the Chief Justice and the Chief Executive: Ex parte Merryman,” Journal of Supreme Court History, (2006): 262-78