James Buchanan was sworn into office March 4, 1857, armed with the knowledge that the U.S Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott case would be read two days later. In an effort to preserve the Union, Buchanan secretly corresponded with – and lobbied – key members of the Supreme Court to remove the issue of slavery from politics. On the day of his inauguration, Buchanan became the first president to not only endorse a Supreme Court decision, but also ask the country to accept the decision – whatever it may be. Unfortunately, the Dred Scott decision created greater tensions between the North and the South, which made a civil war unavoidable.

On April 23, 1791, James Buchanan was born in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania to the son of an immigrant farmer and merchant. He graduated Dickinson College in 1809 and stated he left “feeling but little attachment towards the Alma Mater.” [1] After graduation he studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1812 and opened an office in Lancaster. Seven years later, Buchanan was engaged to the beautiful and wealthy Ann Coleman, despite her mother’s disapproval of Buchanan who had nothing to offer financially. An economic downturn forced Buchanan to leave home, putting his civic duties before Ann Coleman. Rumors floated he was having an affair, which sent Ann into a panic. She fled to Philadelphia to see her sister, overdosed on laudanum and died. Her death deeply affected Buchanan as “he secluded himself for a few days” and promised to never marry again.”[2]

Buchanan was elected to the United States House in of Representatives in 1820 for five successive terms and with the change of administrations became a Jacksonian Democrat. Jackson appointed Buchanan minister to Russia in 1831, and later became a United States Senator for over a decade. After his time as a legislator, Buchanan gained more experience under President Polk and served as Secretary of State and minister to Great Britain. The election of President Franklin Pierce in 1852 proved to be disastrous for the Democratic party. The introduction of Congress’s Kansas-Nebraska Bill repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which upset many Northern Democrats and thus splintered the party.

Although Southern Democrats were more likely to vote again for Pierce, he was strongly disliked in the North. Buchanan, the next option, held a great deal of experience, opposed extremists in both the North and South and believed in territorial expansion. As the only feasible option in the North who was also acceptable in the South, Buchanan was elected the fifteenth president in 1856. While he avoided a civil war during his presidency, his New York Times obituary claimed he entered “the crisis of secession in a timid and vacillating spirit.” [3] The bachelor president retired to his estate “Wheatland” in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and died on June 1, 1868. Buchanan left with his final words, “I have always felt and still feel that I discharged every public duty imposed on me constitutionally. I have no regret for any public act of my life.” [4]

Personal Characteristics

James Buchanan’s striking appearance picked him out of any crowd. He stood “a tall, broad shouldered young man with wavy blonde hair” and ” had developed an odd posture” [5] . Marked by a fair complexion and large forehead [6], he had a defect in one eye that forced him to tilt his head forward and sideways to show “attentive interest” [7]. In conversation, Buchanan’s appeared “vain, formal, solemn and precise; yet withal kindly and gently, always eager to settle disputes without force and solve problems by a friendly and pleasant meeting of minds” [8].

Buchanan felt most comfortable with the southern wing of the Democratic Party in regards to his personal relationships and personal values on the preservation of the Union. He agreed with the South’s view of popular sovereignty, which claimed the people in a territory could not deny slavery until they became a state. Buchanan held disdain for Republicans and abolitionists, seeing them as a threat to preserving of the Union. He promised a southern Senator that his greatest wish would be “to arrest if possible, the agitation of the Slavery question at the North and to destroy sectional parties.” [9]. In every way, Buchanan was the perfect “dough face,” a northerner with southern ideologies.

Key Events

The election of 1856 took place during a major shift in party identification, which historian Michael F. Holt believes was the result of “sectional, social, and political turmoil” [10]. It was a contest among James Buchanan, Republican John Fremont, and Know-Nothing Party Millard Fillmore. The Kansas-Nesbraska Act in May of 1854 had re-opened tensions of the extension of slavery in the territories that both Fillmore and Fremont participated in. Buchanan won the 1856 presidential election because he was out of the country during the sectional crisis in Kansas, a Northerner from an important state and accepted in the South [11]. Fillmore could only earn southern votes and Fremont could only Northern. Buchanan was identified as a safe option to prevent Republican radicalism and restore the Union.

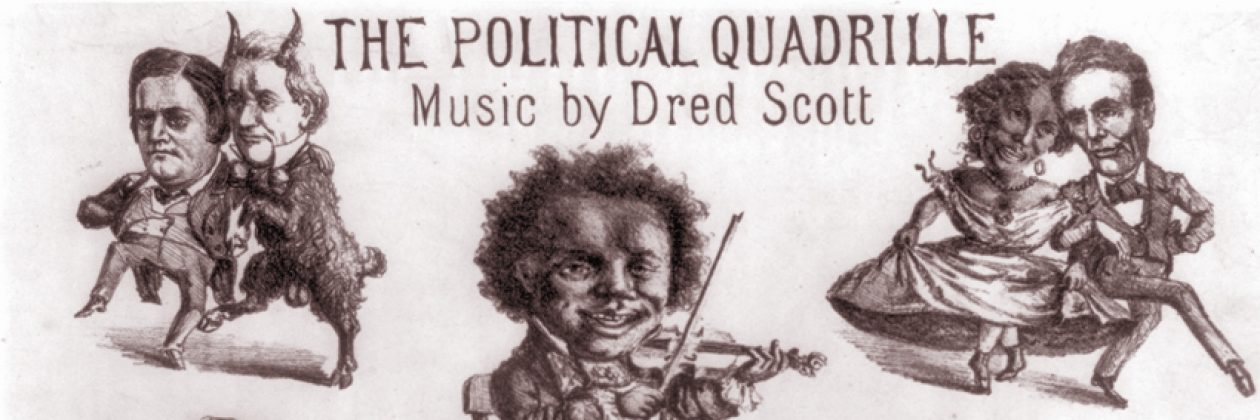

President-elect James Buchanan saw the Dred Scott case as a gateway to “destroy the dangerous slavery agitation and restore peace to our distracted country.” [12] He was in search for a way to prevent the Northern Democrats from alienating themselves from the Union. If the Supreme Court declared the Missouri Compromise [13] unconstitutional on the basis that Congress lacked power to limit slavery in the territories, Buchanan believed the slavery issue between the North and South would end. In a series of confidential letters to two Supreme Court Justices John Catron and Robert Cooper Grier, Buchanan secretly influenced the decision of Dred Scott to rule in his favor. Buchanan also hoped this case would destroy the Republican Party, whose main platform was federal legislation prohibiting slavery in the territories.

President Buchanan stated in his inaugural address, “To this decision, in common with all good citizens, I shall cheerfully submit… to whatever this may be” [14]. His intervention with the other justices made him aware that the Court would declare the Missouri Compromise invalid; however, when he alluded to the Dred Scott case, Buchanan assumed it would settle a different issue – if a territorial legislature could prohibit slavery [15]. This issue had not been discussed in the Court case and was not mentioned in either of Catron’s or Grier’s letter. Buchanan believed if Congress could not forbid slavery in the territories, Congress could not give that power to a territorial legislature. While President Buchanan had intended to quell the Northern agitation against slavery, his speech alone served as a catalyst to Northern hostility.

In 1857, Buchanan had the chance to smooth tensions in the North with the settlement of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. This permitted the two territories to decide whether or not to permit slavery, which resulted in violence between free-soilers and slaveholders, known as “Bleeding Kansas.” [16] Afterwards, a meeting in Lecompton, Kansas proposed a state constitution to authorize slavery which Buchanan supported. He asked Congress to accept this constitution and admit Kansas as a slave-holding state; however, this decision was rejected by a large majority of Congressmen. This infuriated Southern Democrats and only provoked the slavery agitation even further. President Buchanan may have won sympathy in the South but barely any respect and further alienated himself from the North.

On December 3, 1860, President Buchanan delivered his Fourth Annual Message to Congress addressing the increasing tension between the North and South. While Buchanan did not explicitly grant the South the right to secede, the impact of his message did not dissuade it. He blamed Northern states for their open rejection of the Fugitive Slave Act. Buchanan asserted if the State legislatures did not:

“repeal their unconstitutional and obnoxious enactments… it is impossible for any human power to save the Union… [and] In that event the injured State, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the government of the Union.” [17]

South Carolina was the first state to secede on December 20, 1860, claiming Fort Sumter new land for the Confederacy. President Buchanan sent solders to reinforce the fort but the mission failed. Although he escaped impeachment; the issue over the fort cost him members of his cabinet and his deep-seated ties to the South. Buchanan stated since South Carolina’s federal officials resigned, the Executive did not have military power to enforce the law. Because of this inaction, historian Jean Baker believes Buchanan had “given the South a blank check on which they soon wrote the name of nearly every federal installation in the Lower South” [18].

Newspapers ran with stories of a Buchanan’s efforts to aide secession, which provoked Garrett Davis of Kentucky, on December 15, 1862, to try to censure him. Davis stated Buchanan, former President, sympathized with the “conspirators and their treasonable project” and did nothing to prevent the rebellion [19]. Historian Phillip S. Klein wrote that even though the resolution did not pass, Buchanan still faced the public “censure and condemnation” [20].

Further Readings

First hand accounts of Buchanan are found in the Dickinson College’s archives “Correspondence of James Buchanan” (1819-1866). Materials by Buchanan can be seen in Dickinson College’s compiled “James Buchanan Resource Center.” James Buchanan’s opinions of the outbreak of the Civil War can be found in “Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion” (1866). Phillip S Klein, wrote a modern biography titled President James Buchanan (1962). John W. Quist and Michael J. Birkner’s James Buchanan and the Coming of the Civil War reveals notable historian’s perspective of President Buchanan during and after his time as president. Kenneth M. Stampp’s describes Buchanan during the most intense years of his presidency in American in 1857 (1990).

Works Cited

[1] Philip S. Klein, President James Buchanan: A Biography (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962), p. 12

[2] Ibid., 32

[3] John W. Quist and Michael J. Birkner, James Buchanan and the Coming of the Civil War, (University Press of Florida, 2013), 138

[4] American National Biography Online, s.v., “James Buchanan,” accessed February 22, 2015, http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-00170.html?a=1&f=James%20Buchanan&g=m&ia=-at&s=500&ib=-bib&d=500&ss=859&q=7104

[5] Klein, p. 21

[6] James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Vol. VII, (New York, Bureau of National Literature, 1897), p. 2952

[7] Klein, p. 21

[8] Ethan Greenberg, Dred Scott and the Political Court, (Plymouth, UK, 2010), p. 66

[9] Kenneth M. Stampp, America in 1857, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990),p. 48

[10] Michael J. Birkner, James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s, (London, Associated University Press, 1996), 38

[11] Ibid,p. 29

[12]Quoted in Swisher p.610, Draft, James Buchanan to R.C Grier, Nov 14, 1856, Buchanan Papers

[13] The Missouri Compromise decided in 1820 admitted Missouri as a Slave state and Maine a free state. It also stated, with the exception to Missouri, slavery was prohibited in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36 30′ latitude. Congress used this to determine if a state could allow or deny slavery in the territories west of the Mississippi.

[14] James Buchanan, “Inaugural Address,” African American Newspapers, March 5, 1847, Accessed February 25, 2015

[15] Kenneth M. Stampp, America in 1857, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990), 93

[16] James A. Banks, et al., eds., United States: Adventures in Time and Place (New York: McGraw-Hill School Division, 1999), 463

[17] James Buchanan, “Fourth Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union,” December 3, 1860, Accessed February 25, 2015, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29501.

[18] Michael J. Birkner, James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s, (London, Associated University Press, 1996), p. 169

[19] Klein, p. 410

[20] Klein, 410