On Monday, February 23, 1857, Robert Grier recited in a long, confidential letter to President-Elect James Buchanan the detailed history of the Supreme Court’s secretive deliberations in the Dred Scott case. Grier wrote to Buchanan he would not let any one know “about the cause of our anxiety to produce this result” which ran “contrary to our usual practice” [1]. While it was a bold and perhaps unethical move, it was not unusual for the experienced and strong-willed associate justice. Grier agreed to concur with the majority in an effort to support Buchanan and save the Union.

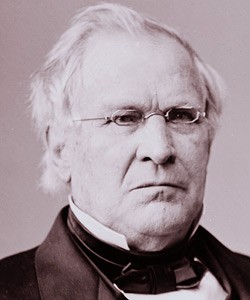

Robert Cooper Grier was born March 5, 1794 in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, to Isaac Grier and Isabelle Cooper. His father was a schoolmaster and Presbyterian minister. In 1811, Grier attended Dickinson College and graduated a year later. Grier taught at Dickinson and then succeeded his father as headmaster at Northumberland Academy, while simultaneously studied law. In 1817, he was admitted to the bar and in 1833 Grier was appointed judge of Allegheny County.

He was initially a Federalist, supporter of a centralized government, and then proclaimed himself a Democrat. He was an active member of the Presbyterian Church; nonetheless, he still had an aggressive character. John William Fletcher White, associate law judge of Alleghany County revealed, “he was a man of quick perceptions, decided convictions, and positive opinions, and like most men of that cast, inclined to be arbitrary and dictatorial.” [2]

On August 4th, 1846 President James Polk appointed Grier to the United States Supreme Court, where he joined another Dickinsonian, Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. Grier was known as a “dough-face”, a northern Democrat sympathetic to slaveholding in the South. Bordering the slave-holding state of Maryland, Grier had to rule on cases concerning runaway slaves. Grier found himself torn between the many in his home state who were against the fugitive slave law and his own Democratic party who favored slaveholders’ rights. When the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed, Grier worried that its enforcement would be destroyed by abolitionists [3]. While Grier made it known his interests were dedicated to supporting slaveholders, his main priority was protecting the Union.

Grier saw abolitionists who tried to take advantage of the law as, “unhappy agitators who infest other portions of the Union… plotting its ruin” [4]. At brink of the Civil War and throughout, Grier first and foremost a Union man, detested the secession of the southern states. In a letter to Grier, Ulysses S. Grant wrote and applauded him for being “able to render to your country in the darkest hours of her history by the vigor and patriotic firmness with which you held the just powers of the Government, and vindicated the right of the nation under the Constitution” [5].

In the summer of 1867 Grier suffered from a stroke, leaving him partially paralyzed. His peers on the Supreme Court to persuaded him to resign. Justice Grier resigned from the bench on January 31, 1870, with the remaining justices commenting on his “great original vigor.” Collectively they agreed Grier brought to the court, “an almost intuitive perception of the right; with an energetic detestation of wrong; with a positive enthusiasm for justice; with a broad and comprehensive understanding of legal & equitable principles…”[6]

Personal Characteristics

Grier was a large, muscular man, standing six feet tall, “somewhat corpulent…”with a “ruddy complexion, and a most agreeable and good-natured face.” [7] David Paul Brown, lawyer and abolitionist, described Grier to have an “occasional roughness of manner, and harshness of voice” due to a difficult childhood [8].

D.P Brown commented when Grier was forced to go against his liberal policies he seemed to “be swayed by a desire to perform his duty, however he may sympathize with the oppressed.” [9] Serving on the Court with Grier, Justice Campbell spoke highly of his “vigorous thought” and “large mindedness,” and despite his temper, he was able to gain the respect of the other justices and attorneys who argued before him on the Supreme Court [10].

Key Moments

After the Christiana Riots on September 11, 1851, Grier, along with D.P Brown served as one of the two judges at the trials. A white miller, Castner Hanway was charged with treason for inciting a war against the United States to aid fugitive slaves. Grier, a supporter of The Fugitive Slave Law, shocked the court when he ruled that even armed violence against law enforcers did not amount to treason. Grier did, however; make it known that his truest sympathies were with the slave-catchers and denounced the abolitionists as the perpetrators of the riot. [11]

In 1854-5, The Wheeling & Belmont Bridge Company claimed that Justice Grier used a personal connection to persuade the court to rule against the company’s business. They also asserted he “solicited a bribe from their agents” and “leaked the opinion of Supreme Court early.” Representative Hendrick B. Wright, the only Pennsylvanian on the Committee, investigated the claim; however, he revealed while there was not enough evidence to remove him from the bench. Wright did conclude that Grier was clearly comfortable using a familiar associate to influence the decision [12]. Grier’s lack of punishment led him to believe this sort of behavior could be tolerated, which he pursued once again to influence the Dred Scott decision.

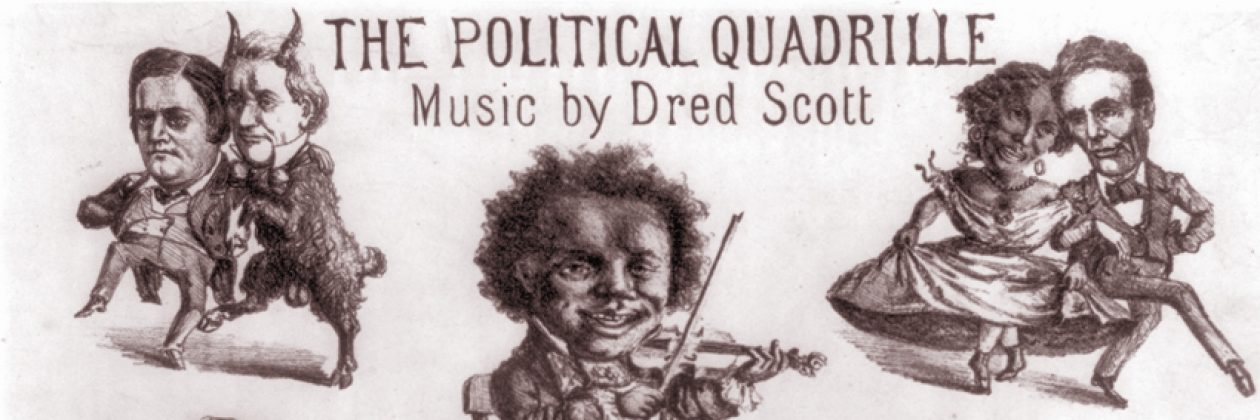

President-elect Buchanan believed declaring the Missouri Compromise [13] unconstitutional in the Dred Scott case would remove the issue slavery out of the territories. Justice Catron, a close friend to both Grier and Buchanan, instructed Buchanan to persuade Grier in joining the majority opinion. As a non-slaving holder northern Democrat, Grier’s opinion would add weight to the Court’s decision. After Buchanan wrote to Grier, on February 23, 1857, Grier responded that he and Justices Taney and Wayne would rule that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. Grier understood his importance to the case as well as the importance of this case for the Union. He secretly revealed to Buchanan that the decision would be delayed due to Taney’s frail health and would be announced before Inauguration, giving the President-elect time to prepare his address. The court’s decision in the Dred Scott case did not resolve the issue of slavery and perversely further created a division between the North and South.

Grier, a believer in the Union, was infuriated by the secession of South Carolina and Buchanan’s refusal to take action in the midst of this crisis. Buchanan just wanted peace and believed if a state seceded there was nothing he could do. On December 29, 1860, Grier wrote to a friend, Aubrey Smith, “Buchanan is wholly unequal to the occasion — He is surrounded by enemies of the Union… He is getting old — very fast– poor fellow has fallen on evil times.” [14]

Abraham Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861 with the secession of seven Southern states and the creation of the Confederacy. The Prize Cases were argued before the Taney Court in February 1863 to determine the legality of Lincoln’s blockage against Southern ports before Congress declared war. If the Supreme Court decided this action was illegal, the Union would be weakened and the Confederacy would continue to grow [15]. Grier wrote for the slight majority to support Lincoln’s blockade, using the Constitution to grant President Lincoln authority to suppress the rebellions in the South. Grier also ruled the Confederate government lacked legal standing [16].

Richard Dana, Jr., a U.S Attorney of Massachusetts during the Civil War, noted that since Grier’s appointment by President Polk in 1846 his ideologies had shifted. He was a northern Democrat who believed in states rights, trying not to disturb the extremist views in the North and South. Also, at the onsite of the Civil War, Grier disapproved of the Lincoln Administration’s handling of the war. Two years later, his opinion, according to historian James F. Simon “could not have been more perfectly tailored to the Lincoln administration’s specifications ” [17].

Further Readings

Grier’s correspondence can be found in Dickinson College’s Archives that reveals letters written to and from Grier. David Paul Brown’s The Forum, Or Forty Years Full Practice at the Philadelphia Bar, offers insight into Grier’s time on the Supreme Court. John Basset Moore compiled he Works of James Buchanan, Comprising His Speeches, State Papers, and Private Correspondence that also holds Grier’s letters to Buchanan. Jonathan Katz’s Resistance at Christiania (1974) serves as a detailed account of Grier’s involvement in the Christiania Riots. Daniel J. Wisniewski’s article “Heating Up a Case Gone Cold: Revisited the Charges of Bribery and Official Misconduct Made against Supreme Court Justice Robert Cooper Grier in 1854-55” offers an interesting perspective on Grier’s unethical behavior before Dred Scott.

Works Cited

[1] R. Grier, to James Buchanan, Washington D.C., February, 23 1857. As printed in The Works of James Buchanan, Comprising His Speeches, State Papers, and Private Correspondence. Vol. 10, ed. John Bassett Moore, (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1908-1911), p. 106.

[2] J.W.F White, The Judiciary of Allegheny County, (Philadelphia: Collins, Printer, 1883) p.33

[3] Ethan Greenberg, Dred Scott and the Political Court, (Plymouth, UK, 2010), p. 173

[4] James F. Simon, Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney, (New York, Simon & Schuster, 2006),p. 94

[5] John Y. Simon, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Vol. 20: November 1, 1869-October 31, 1870, (Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1967). p. 52

[6] John William Wallace, Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the United States, 1870. Vol. VIII, (Washington, D.C: W.H & O.H Morrison), p. viii

[7] David Paul Brown, The Forum, Or Forty Years Full Practice at the Philadelphia Bar, (Philadelphia:R.H. Small 1856), p. 100

[8] Jonathan Katz, Resistance at Christiania, (New York: Crowell, 1974), p. 181

[9] Ibid., p. 181

[10] Brian McGinty, Lincoln and the Court, (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 26

[11] Greenberg, p. 173

[12] Daniel J. Wisniewski, “Heating Up a Case Gone Cold: Revisited the Charges of Bribery and Official Misconduct Made against Supreme Court Justice Robert Cooper Grier in 1854-55”Journal of the Supreme Court (2013), p. 13

[13] The Missouri Compromise decided in 1820 prohibited admitted Missouri as a Slave state and Maine a free state. It also stated, with the exception to Missouri, slavery was prohibited in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36 30′ latitude. Congress used this to determine if a state could allow or deny slavery in the territories west of the Mississippi.

[14] Letter from Robert Cooper Grier to Aubrey Smith, December 29, 1860

[15] James F. Simon, p. 225

[16] Ibid p. 230

[17] Ibid, p. 231