June 4, 2015

By: Julie Foong

Today, we started heading out of the hostel at 9:30am to meet Professor Brito’s friend, Cristiane, who is working on her degree in history and is a director of a public school, for a city tour. Our first stop was the Igreja de Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Homens Pretos (Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men) which was built 300 years ago and is one of the symbols of Afro-Brazilian culture in São Paulo. In its immediate surroundings, there was a statue of a mother breast feeding a child. In the context of slavery, the children that benefited from this lady’s breast milk would not necessarily be her own, but of her master’s children. This statue was a comment on the history of the mixing of race, as some masters would force themselves on their slaves. Often time, these slaves would take on the role of the mãe preta (Black mother), and care for the master’s children (Goldstein, 2013:41). In placing this symbol in front of a church, it also puts forth the idea that she was prepared by God for this role, to become a mother for all of us and she is seen by many Brazilians as a quasi Saint.

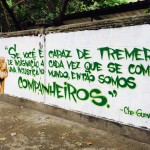

Along the way, we encountered buildings covered in specific graffiti. Professor Barnum recounted a trip 2 years ago, when he recognized certain buildings that were being occupied by Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto (Brazil’s Homeless People’s Movement) which is loosely affiliated with the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra (Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement, aka MST). The homeless would enter unoccupied buildings and stay in them for a period of time, which then allowed them to fight for the rights of the buildings to achieve housing and shelter. It is one of the largest and most successful movements in Brazilian history. Although MST has not managed to win the occupied buildings we passed, they were branded with the logo and it was evident that they have a footprint on the urban landscape.

Next, we had a juice break at a local neighborhood store. I was fortunate enough to sit at the table where Cristiane joined us and our professors provided the translation. Alejandro asked the first question: “What are you passionate about,” to which she answered that she was an educator, an elementary school teacher. She felt that she wanted to impact the next generation and help mold their attitudes regarding class, race, and other social factors before society solidifies the preconceived notions and prejudices that guide adults. This prompted my series of questions about what kind of situations could stimulate such teaching moments, how the children typically react, and a relation back to psychological treatments. Cristiane responded that the children she worked with typically come from bad situations and they have a tendency to enact the violence and language they observe at home and in their communities. When they approach their peer in the same way, she will get them to reflect about why it is not right, which usually influences the children to realize the impact of their actions and guide their future behavior. As a Psychology major, I was interested in her coping mechanisms as she deals with such tricky situations. She mentioned that it does get hard and she gets sad. Although therapy is an option for educators to pour their emotions out, it is costly here as well, at about US $100 per session (my guess of about 50-60 minutes). When limits get reached, some teachers cannot continue and choose to leave their profession. Despite the difficulties she shared with us, it was also heart-warming to hear of her determination and desire to help others. In the counseling profession, counselors typically have a clinic with a handful of other counselors who are able to provide professional opinions and a listening ear. It is my hope that educators will understand this and somehow apply it to their profession and colleagues.

During this time, another group of students had engaged in a meaningful conversation which was prompted by our visits to the multiple churches. Each was curious with each other’s religious beliefs and started to question how and why they believed them, given that many contradictions existed between and within the religions they were familiar with. They related it back to culture and shared their thoughts on how society impacted the religions, but also how the religions impacted society. This dualism has helped create the uniqueness of the many countries in the world, of which we were starting to notice in Brazil, where its people are mainly Catholic.

We did a few more other buildings and headed to the Municipal Market for lunch. The market displayed and sold many varieties of fruits that are not found in the United States. However, fruits like rambutan, dragon fruit, soursop, and mangosteen, can be found in my home, Singapore, and that made me really happy to see familiar fruits. The vendors even had raw cacao, from which cocoa is derived. It is commonly prepared as a fruit juice in Brazil, which tastes nothing like the manufactured product of chocolate. It has many health benefits like reduction of blood pressure and the protection of one’s nervous system (Wilson, 2014). The market was crowded with tourists, locals, and hungry shoppers. Eventually, we settled down at Mortadela da Cidade, which served Italian-style sandwiches, where the cheese was surrounded by plenty of meat and stuffed between a baguette. Fun fact, Brazil has the most Italians, Japanese, and Arabs, outside of their native countries and regions. We were satisfied and had good conversations that enabled us to continue on with our adventure.

In the early evening, we were offered an optional activity of attending the 15th Annual LGBT Cultural Festival. Besides Professor Barnum and Professor Brito, four of us decided to join them. White tents were set up, which we saw earlier in the day, were now bustling and hustling with activity, offering food, beverages, and souvenirs. There was also a stage in the courtyard nearby where drag queens and other performers were strutting their talents and entertained the crowd that gathered.

We sure have gotten to experience the many flavors of São Paulo and are excited to see what else the city will offer in our time here.

Goldstein, Donna M. (2013) Laugher Out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality In a Rio Shantytown. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA.

Wilson, S. (2014). Raw cacao vs cocoa: What’s the difference?. Retrieved from www.foodmatters.tv/content/raw-cacao-vs-cocoa-whats-the-difference