On Thursday September 21st, I attended a Clarke Forum event discussing the Beirut Barracks Bombing of 1983, its precursors, and its ramifications. I was unfortunately unable to attend in person due to a mild case of vertigo, but the staff at the Clarke Forum do a wonderful job of livestreaming their events. It was done panel-style with three guest lecturers: Mireille Rebeiz, a professor here at Dickinson College, James Breckenridge, a former dean at the U.S. Army War College, and Michael Gaines who represented the Beirut Veterans of America and whose brother died in Beirut.

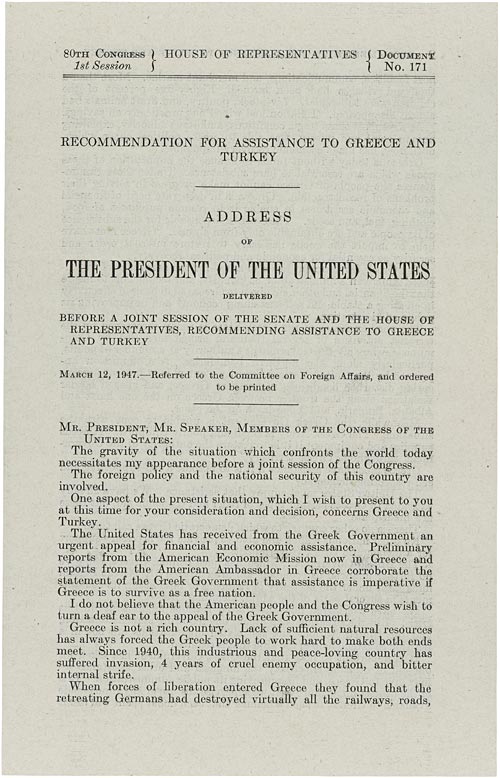

I found the event very fascinating. Coming into it, my knowledge of Lebanese history and American interference in the state was limited. Dr. Rebeiz, who grew up in Lebanon, began the event with historical context to U.S. interference and the bombing. Lebanon, a small state situated between numerous countries, is vastly religiously diverse, with its population representing not only different religions, but different sects and denominations. Hence, religious conflict has been a long-told tale in the country, starting with their first religious war in 1860 while it was still part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1958, the U.S. had it’s first intervention in the state when Lebanese president Camille Chamoun wanted to extend his term. The U.S., operating under the Truman Doctrine, answered Chamouns call. This occurred in a post Sikes-Picot and Balfour Agreement Lebanon, where the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was headquartered in the country, and the Cairo Agreement allowed them to fight against Israel at the Lebanon/Israel border. This increased religious conflict because many Christians in Lebanon advocated more for peace with Israel, while many Muslims of the country wanted to stand in solidarity with their Arab neighbors.

The Lebanese Civil War began in 1975 and lasted until 1991. Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982 during the war, partly to fight the PLO. Then, the Reagan Administration decides to deploy troops in 1982 to try to quell the ongoing conflict and violence. This begins the story of the bombing in 1983.

The extent of Lebanon’s sectarian and religious violence was surprising to me–I was no

t aware how religiously diverse the country was, with several competing sects within several competing religions. I never learned about the U.S. involvement in Lebanon in high school, nor the Lebanese Civil War in general. It made sense to me that interference would be justified with the Truman Doctrine, though the U.S.’s occupation for 2 years is definitely a liberal use of such policy. In foreign policy, the U.S. is quite picky about where they intervene with humanitarian or democratic justifications. If what was happening in Lebanon was occurring in another region of the world, I wonder if the U.S. would have still intervened, or whether the intervention was solely due to Lebanon’s strategic position.

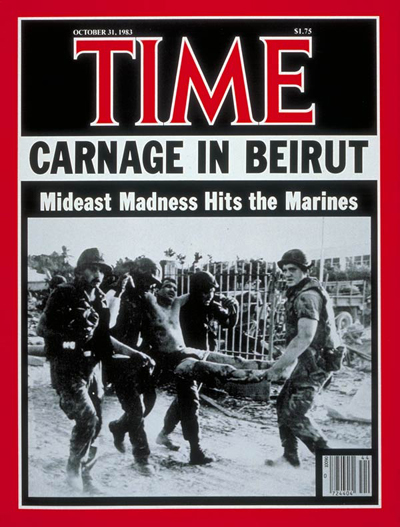

The second speaker, James Breckinridge, prefaced his part of the event with an acknowledgement of his retrospection and subjectivity as a Beirut veteran, which I found interesting. He emphasized the value of historical memory, a theme of the event in whole. He described the arrival of the Marine Corp in the country, and how the power vacuum that formed after the Lebanese president was assassinated was the catalyst for further instability and violence, especially in regards to the PLO and their Christian adversaries. The Marine Corp was involved directly with the Lebanese army, which was mostly Maronite Christian. This caused anti-U.S. conflict as many Lebanese saw that move as the Marines taking sides. The U.S. embassy was bombed, and the airport was relentlessly attacked. Then, on October 23, 1983, 241 soldiers killed by a detonated truck bomb, which was the largest loss of life on the Marine Corp in a single day since Iwo Jima.

The Marine Corp was involved directly with the Lebanese army, which was mostly Maronite Christian. This caused anti-U.S. conflict as many Lebanese saw that move as the Marines taking sides. The U.S. embassy was bombed, and the airport was relentlessly attacked. Then, on October 23, 1983, 241 soldiers killed by a detonated truck bomb, which was the largest loss of life on the Marine Corp in a single day since Iwo Jima.

It makes sense to me that non-Maronite groups in Lebanon would see the Marines as an adversary. The U.S. was and still is a widely Christian country, and their involvement with the army made it known that their mission as more than just peace keeping. I emphasize with the the Reagan cabinet’s debate between interference and noninterference, though wonder how much of the Marine’s (and the Army’s) interference was done on orders from the U.S., or rather done in supposed necessity at the moment. I also found it particularly interesting that the embassy bombing  the entire CIA contingent in Beirut, and the challenges that arouse from the sudden absence of intelligence occurring from such a strategic attack. For such a monumental event (one compared to Iwo Jima!), I’m surprised it has not stood the test of time in history education and in the greater collective memory. My great uncle was an Okinawa Sugar Loaf veteran, and the forum made me think of him and the dying contingent of WWII vets, and how their experiences will soon be history, rather than memory. Iwo Jima and other destructive WWI battles like those on Okinawa iare greatly remembered–how can we develop those same remembrance principles with other attacks on U.S. citizens?

the entire CIA contingent in Beirut, and the challenges that arouse from the sudden absence of intelligence occurring from such a strategic attack. For such a monumental event (one compared to Iwo Jima!), I’m surprised it has not stood the test of time in history education and in the greater collective memory. My great uncle was an Okinawa Sugar Loaf veteran, and the forum made me think of him and the dying contingent of WWII vets, and how their experiences will soon be history, rather than memory. Iwo Jima and other destructive WWI battles like those on Okinawa iare greatly remembered–how can we develop those same remembrance principles with other attacks on U.S. citizens?

The third speaker stressed that “everyone has a story” and how “it’s all of our duties to remember.” This is why not only memorials, but also educational events like this one are crucial in historical education, empathy, and remembrance. The 1983 Beirut Barracks Bombing was influential due to the resulting politics of Southwest Asia, yes, but it was also greatly influential in loss of life, and its more localized scale should not be overlooked. I am glad I was able to hear such a lecture, and learn more not only about U.S. intervention in Lebanon, but also Lebanon as a country and the veterans who served there.